The new five-year exhibition cooperation project between the West Bund Art Museum in Shanghai and the Centre Pompidou in France kicked off with "Reshaping the Landscape", which features nearly 70 pieces from the Centre Pompidou's collection. The exhibition was curated by Christian Briend, curator of the Centre Pompidou, director and chief curator of the Contemporary Art Collection Department of the National Museum of Modern Art in France, who was also the curator of the previous West Bund Art Museum's Raoul Dufy retrospective, "Melody of Joy".

As the director of the modern art department of the Pompidou Center, Christian Briand is mainly responsible for art collections before 1950, and his research expertise focuses on Fauvism and Cubism. In May next year, he will plan a large-scale Cubism opening exhibition for the Pompidou Center in Seoul. The Paper recently interviewed Briand and asked him how to understand the "reshaping" of landscape in modern art and the Chinese aesthetic elements that are vaguely borrowed from Western landscape paintings.

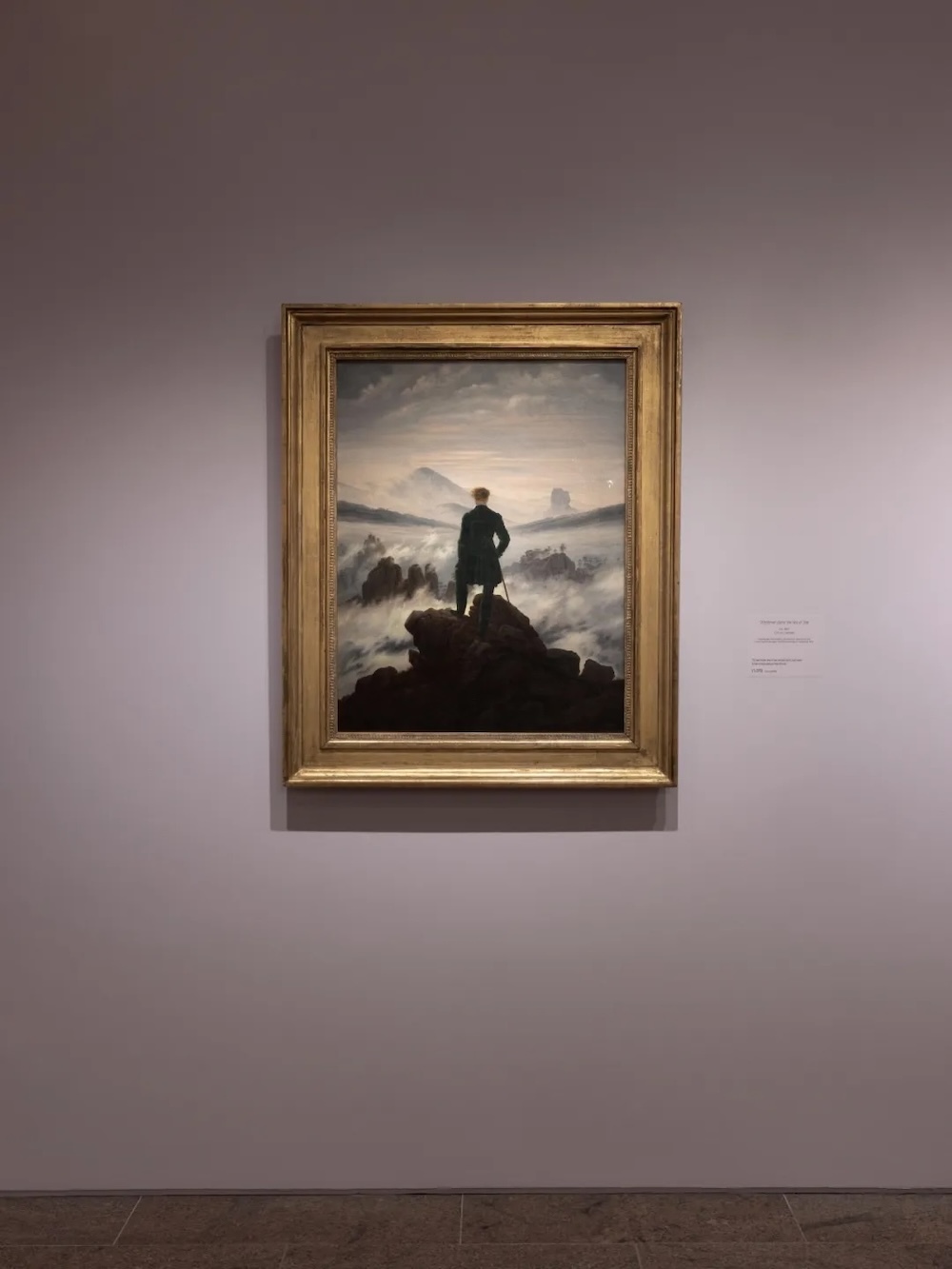

Christian Bryant sees curating as constructing a movie script—it must have a dramatic opening and ending. In this exhibition, the first work is Peter Doig's "100 Years Ago (Carrera)", in which a lone rower turns and stares at the audience, with a vast seascape behind him. This questioning gaze that goes straight to the heart is like asking every viewer: "What is your relationship with nature and landscape?"—this is the ideological anchor deliberately set by the curator.

Exhibition entrance, Peter Doig’s “100 Years Ago (Carrera)”. West Bund Art Museum and Centre Pompidou’s five-year exhibition collaboration project, permanent exhibition “Reshaping the Landscape: Centre Pompidou Collection Exhibition (IV)”, exhibition site, West Bund Art Museum, photo by Alessandro Wang

The final chapter is a video called “Echo” by Chinese-Luxembourg artist Xie Sumei. It forms a mirror contrast with the positive gaze of the male image in Doig’s work: in the video, the female artist in a red dress, Xie Sumei herself, plays the cello in the magnificent scenery. The music she plays seems to be an inner monologue, as if waiting for the feedback of nature.

The last work in the exhibition, Xie Sumei, Echo, 2003

The echoes brought by the two works at the beginning and the end form a poetic structure, extending the meaning of the "relationship between man and nature" - the landscape is not only a reproduction of nature, but also a carrier of the artist's thinking to perceive the world.

Portrait of curator Christian Briend ©Hervé Veronèse

The Paper: This exhibition is the first permanent exhibition in the new round of the five-year exhibition cooperation project between the West Bund Art Museum in Shanghai and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Why is "landscape" the theme? What tradition does "landscape" have in Western painting? How does modern art continue this tradition? Why is the exhibition titled "Reshaping"?

Brian: This is the fourth permanent exhibition since the cooperation between the Pompidou Centre in Paris and the West Bund Art Museum in Shanghai began. The exhibition chose "Landscape" as the theme after the previous "Portrait" theme exhibition. This is a project I have been preparing for a long time, and I am very happy to present it for the first time at the West Bund. In fact, this is an exhibition theme that the Pompidou Centre has never planned before. In the past, we have held more than ten portrait-themed exhibitions, but never touched on landscape. If we broaden our horizons to the entire art world, exhibitions on this theme are also quite rare. There has never even been a special exhibition on the evolution of landscape art since the 20th century. I think this is indeed a gap that needs to be filled, and the Pompidou Centre is honored to organize this exhibition.

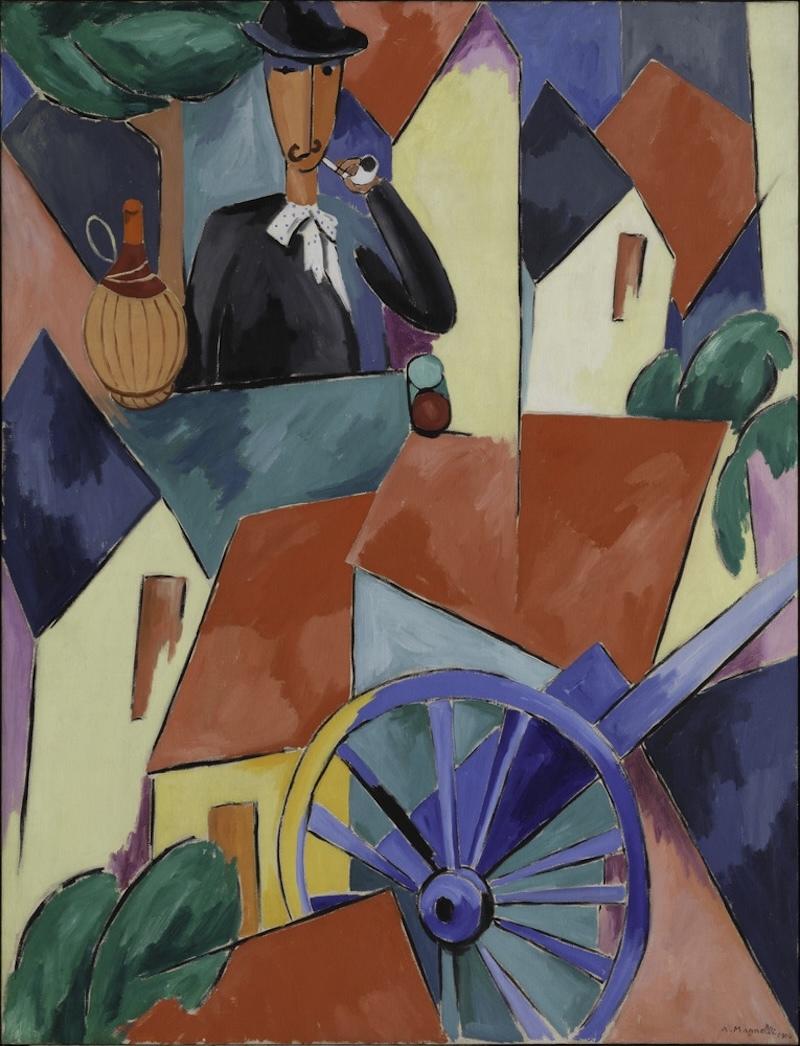

Alberto Magnielli, Man with a Cart, 1914, oil on canvas, 170×130cm, donated in 1997 to the National Museum of Modern Art - Industrial Design Center, Centre Pompidou, Paris

In the Western art tradition, independent landscape painting is a relatively recent genre, with its origins dating back to the early 19th century. Contrary to current perceptions, for centuries the Western art world has always regarded landscape painting as a minor genre, mainly as a decorative element of historical and religious scenes. It was not until the Romantic period that landscape painting began to become an independent genre. The golden age of Impressionism came at the end of the 19th century, and its predecessor was the Barbizon School, so there was a "Barbizon School-Impressionism" inheritance relationship. After entering the 20th century, the modernist movement and avant-garde art emerged one after another, including Fauvism, Cubism, Surrealism and Abstractionism, all of which used landscape themes as a carrier for creative experiments. This is why I set the theme as "Reshaping the Landscape", the core idea is that although we have inherited the tradition of landscape painting (even if this tradition itself is not long-standing), artists have recreated "landscape" through various techniques since the 20th century.

West Bund Art Museum and Centre Pompidou’s five-year exhibition collaboration project, permanent exhibition “Reshaping the Landscape: Collection Exhibition of Centre Pompidou (IV)”, exhibition view, West Bund Art Museum, photo by Alessandro Wang

The Paper: Which works in this exhibition deserve special attention? Are there any "lost pearls" that have not been noticed by mainstream art history and are presented in this exhibition?

Brian: This exhibition is divided into seven themed exhibition areas, and each exhibition area selects a representative work with forward-looking and benchmark significance as an "introduction". In terms of exhibition design, the works in each exhibition area are not strictly arranged according to the time clue. Take the fifth exhibition area "Overlooking the View" as an example, André Derain's classic work "Two Barges" is exhibited; while the third exhibition area "Dizziness" presents Georges Braque's representative work "Landscape of L'Estaque" during the Fauvist period. This work was also selected as the core image of the main visual poster of the exhibition. It is worth noting that this exhibition presents a distinct diversified feature in the selection of media. In addition to traditional paintings, it also covers a variety of contemporary art forms such as film, video art and installation art.

At the exhibition, André Derain’s classic work “Two Barges” served as the introduction to “A Bird’s-Eye View”.

The most fascinating thing about this kind of thematic exhibition is that it can activate the Pompidou Museum's complex collection system. Just like last year, when my colleague Frédéric Paul curated the "Portrait" exhibition, he rediscovered many forgotten masterpieces of French artists. During the curatorial process of this exhibition, I also had unexpected gains: for example, the Hungarian painter Lajos Tihanyi, an artist who died in Paris and whom I accidentally discovered during my research in Budapest, I unexpectedly found his wonderful works from the 1920s in the Pompidou warehouse. Such "rediscovery" cases are everywhere in the exhibition, and they form a wonderful dialogue with classic works such as Braque and Zao Wou-Ki.

Lajos Tiani, Rue de la Glacier, 1925, oil on canvas, 100 x 65 cm, gift from the Republic of Hungary to the National Museum of Modern Art – Centre Pompidou, Paris, 1970

The Paper: The exhibition covers a century of art from 1906 to the present, covering a variety of important art schools, such as Fauvism, Cubism, Surrealism, Abstractionism, etc. How do you view the influence of these schools on landscape art? From the natural landscape of Impressionism to the artistic transformation of Modernism, what do you think has happened to the status and significance of "landscape" in art history?

Brian: In the development of art in the 20th century, major schools such as Fauvism, Cubism, Surrealism and Abstractionism have had varying degrees of influence on landscape painting. This exhibition has set up four independent exhibition areas to present the artistic explorations of these schools:

The Cubism exhibition area "Constructed Space" is represented by artists such as Braque and Picasso, showing how they deconstruct traditional landscape images and reconstruct space through geometric reorganization.

Cubism exhibition area, West Bund Art Museum and Centre Pompidou’s five-year exhibition cooperation project, permanent exhibition “Reshaping the Landscape: Pompidou Centre Collection Exhibition (IV)”, West Bund Art Museum, photography: Alessandro Wang

The Fauvist exhibition area "Dizzy" focuses on the innovation of color language. The works in this exhibition area are characterized by a strong sense of light, presenting some works of more contemporary artists after the Fauvism. These works vividly interpret the visual theme of "sunlight" through the use of large areas of bright yellow blocks. The starting point of our exhibition is set in 1906, which is the climax of the Fauvism movement. In my opinion, this is the turning point when the "landscape reproduction paradigm" was completely innovated. Although Fauvism inherited the color revolution of Impressionism, facing the dilemma of the Impressionist brushstrokes becoming loose and the themes becoming diluted at that time, artists such as Matisse and Derain responded with a new visual grammar. In particular, they subverted the color system, no longer imitating the true colors of nature, but translating the subjective feelings of artists when facing the landscape. This revolution of "emotionalizing" the landscape coincided with the birth of modernity and paved the way for the entire 20th century art.

The Fauvist section of the exhibition is “dazzled”, the permanent exhibition of the five-year exhibition cooperation project between West Bund Art Museum and Centre Pompidou “Reshaping the Landscape – Exhibition of the Pompidou Centre Collection (IV)”, West Bund Art Museum, Photo: Alessandro Wang

The surrealist exhibition area "Surreal Vision" presents a more obscure landscape expression, mainly using two typical techniques to create a magical or strange surreal mood: one is "repetition", such as repeated elements such as trees and rocks; the other is to break the conventional proportional relationship. For example, in Immendorff's work "Forest of the World", a huge mirror occupies most of the forest.

The surrealist section of the exhibition “Surreal Vision”, the permanent exhibition of the five-year exhibition cooperation project between West Bund Art Museum and Pompidou Center “Reshaping the Landscape - Pompidou Center Collection Exhibition (IV)”, West Bund Art Museum, photography: Alessandro Wang

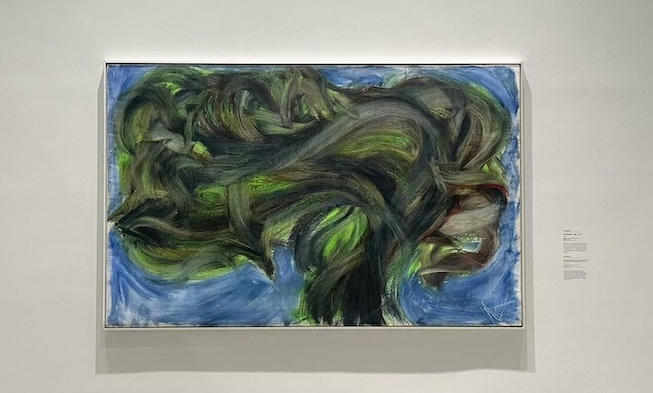

"Abstract" was born between the two world wars. It was not until around 1945 that this kind of abstract form expressed in geometric form began to appear in the United States and Europe at the same time. But I know that the Pudong Art Museum is holding a Turner exhibition (closing on May 10), and his late works actually have a bit of abstract feeling. Many of the works exhibited in our exhibition this time were created after the 1950s. Artists may achieve abstract effects through gestures, hand movements or brushstrokes. But it is not very extreme abstraction. It is a state between concrete and abstract. It may also be related to some movements in nature, such as the flow of clouds or waves in the ocean.

“Abstract Landscape” in the “Abstract” section of the exhibition, “Reshaping the Landscape—Exhibition of the Pompidou Center Collection (IV)”, a permanent exhibition of the five-year exhibition cooperation project between the West Bund Art Museum and the Pompidou Center, West Bund Art Museum, Photo: Alessandro Wang

It is worth noting that with the evolution of these schools, the status of "landscape" in art history has undergone a fundamental change: from an initial marginal subject to an important creative theme that is as important as "portrait". Especially after 1945, abstract landscape works began to appear in larger sizes, giving people a very spectacular feeling. At the same time, this also indirectly reflects the change in the status of landscape painting.

Exhibition view of the “Abstract Landscape” section, Jean Messagille’s work “Conquering Franche-Comté in June”, 1969

The Paper: In Chinese paintings, landscapes are called "shanshui". How do you view the similarities and differences between "shanshui painting" and "landscape painting"? In previous exhibitions at the West Bund Art Museum, the relationship between surrealism and Chinese art was presented; some studies also believe that the writing style of abstract painting was inspired by Eastern art. In this exhibition, how are "surreal vision" and "abstract landscape" described? How are the works of Chinese artists selected and included in the exhibition?

Brian: I am not an expert in Chinese art, but in terms of exploring the integration of Eastern and Western art, the fourth exhibition area, "Abstract Landscape", is the most representative. Although I cannot accurately point out which Western abstract artists were influenced by which Chinese artists, these works more or less contain the aesthetic characteristics of Eastern landscape art. After all, the history of Chinese landscape painting as an independent aesthetic object is more than a thousand years earlier than that of the West.

Although this exhibition does not directly compare this historical dislocation, it presents an intriguing dialogue in the “Abstract Landscape” chapter: on one side are European artists such as Olivier Debré who were influenced by Chinese calligraphy and painting, and whose flowing brushstrokes clearly borrowed from ink painting techniques; on the other side are Zao Wou-Ki, who fused traditional brush and ink with Western modernity.

Exhibition view, Olivier Debré's work "Blue with Yellow Stains (Large Blue)", 1965

In addition to Zao Wou-Ki, another Chinese artist introduced in this exhibition area is Chuang Che. They were both born in Beijing scholarly families. Zao Wou-Ki later moved to France, while Chuang Che moved to the United States. These two artists come from different eras, but their works are both related to abstraction: Zao Wou-Ki began to use abstract techniques to create works after the 1950s, while Chuang Che was influenced by expressionism after moving to the United States. So although they both belong to the category of abstract art, their works show significant differences compared with those of Western artists. This contrast vividly demonstrates the essential differences between Eastern and Western art traditions.

Exhibition site, Zao Wou-Ki's 1954 work "Wind" (left), Zhuang Zhe's 1981 work "Untitled"

In terms of the selection criteria for Chinese artists' works, first of all, the selected works must be within the collection of the Pompidou Center. Especially since the cooperation with the West Bund Art Museum, the Pompidou's collection of contemporary Chinese artists' works has become increasingly rich. Secondly, if it fits the theme of the exhibition, I am very willing to choose works by Chinese artists. For example, Cui Jie's works are in the "Urban Landscape" unit, and I admired her solo exhibition at the West Bund last year. But there are also examples of other artists - Qiu Xiaofei's work "Pot Plants in the Forest", which was recently acquired, was also selected and exhibited in the "Dizzy" exhibition area.

Cui Jie, Beijing International Hotel, 2017, oil on canvas, 150×200×5 cm, donated by the International Committee of the Association of Friends of the Centre Pompidou, Greater China, to the National Museum of Modern Art – Industrial Design Center, Centre Pompidou, Paris, in 2018

The Paper: From easel painting to contemporary installations, how do you view the expansion and reshaping of the traditional art subject of "landscape" by these emerging technologies (such as video, neon lights, and installation art)?

Brian: The biggest change that installation art, video and film have brought to landscape painting is that it allows the audience to immerse themselves in it, rather than presenting it in a two-dimensional way. In the "Panorama" section of this exhibition, Christo's installation work "Wrapped Ground" reconstructs the landscape space in a minimalist way by laying fabric on the ground and covering it with geometric structures.

The exhibition site shows the collaborative work "Pier and Ocean" by French artist François Morellet and Japanese artist Masaru Kawamata.

Then there is the collaborative work "Pier and Ocean" by French artist François Morelet and Japanese artist Masaru Kawamata, who used blue neon lights to simulate the embankment and the ocean, creating a poetic scene through changes in light and dark. It is worth noting that this work actually contains a triple artistic dialogue: in addition to the direct collaboration between the two contemporary artists, it also includes a tribute to Mondrian's artistic concept. The work forms an interesting echo with the "panorama" that was popular in Europe in the 19th century. This architectural form simulates real scenes through circular paintings to create an immersive experience for the audience. At the exhibition site of "Pier and Ocean", the audience can actually step onto the "pier" and step into the "ocean" space composed of lights. A similar immersive experience is also reflected in Veronique Rumar's interactive installation "Green Panorama". These works together expand the participation dimension of traditional landscape art.

Exhibition view, Veronique Rumar’s interactive installation “Green Panorama” Photo: Alessandro Wang

In short, new media allow works to undergo more dimensional changes, allowing the audience to truly "enter" the landscape world constructed by the artwork. But regarding the argument that "painting is dead", my position has become increasingly clear: this is a false proposition.

The Paper: In addition to the perspectives of art schools, the exhibition also presents viewing perspectives, such as "dazzling" (scenery under the sun), bird's-eye view, and panoramic view. How are these two different perspectives combined in the same exhibition? How are the contemporary landscape and urbanization issues of the city expressed through the exhibition?

Brian: This is the core value of this theme exhibition - it breaks through the limitations of a single perspective and reinterprets the theme of "landscape" through diversified expressions and artistic languages. What fascinates me most is the multiple historical dimensions presented by the exhibition: it not only includes the development context of art history, but also the unique creative perspectives of artists in different periods. Therefore, unlike traditional linear narrative exhibitions, this exhibition is more like a kaleidoscope full of possibilities, vividly showing the rich connotations and lasting influence of the concept of "landscape" on artists' creations from the 20th to the 21st century.

Beatriz Milassez, “Lavender and Blue Primeval Forest”, 2016, acrylic on canvas, 48×300 cm, donated anonymously to the National Museum of Modern Art – Industrial Design Center, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 2018

Contemporary artists' exploration of landscape is undergoing a profound paradigm shift - rather than saying that the theme of landscape is outdated, it is better to say that its connotation has shifted from natural fields to urban textures. The work of Senegalese artist Cheikh Ndiaye is a perfect example: in his work, he captures the changes of the old cinema in the Trecheville district of Abidjan. The square composition on the canvas is like a global microscope - colonial architectural heritage, hand-built shop sheds, and American brand advertisements collide here. This "urban chaotic aesthetics" constitutes the most acute contemporary narrative: when the traditional idyllic landscape fades, the collage reality of the post-colonial city becomes a new discourse field, and the juxtaposition of these buildings also forms a unique urban texture.

Cheikh Ndiaye, Cinema in Tracyville with a mosque, 2014, oil on canvas, 192 x 197.5 cm, gift from the Association of Friends of the National Museum of Modern Art in 2016, Contemporary Art Project 2015, Centre Pompidou, Paris, National Museum of Modern Art - Industrial Design Center

More environmental changes, climate issues or urbanization issues are not involved in the exhibition. Because I think these issues can be dealt with more directly through photography. This time, our exhibition mainly uses oil paintings, installations and images. Photography works are not included, so the issues related to globalization are not clearly responded to.

Note: The exhibition will run until October 18, 2026.