In the 19th century, Mexico, after getting rid of the colonial shackles, urgently needed to build its own cultural identity. José María Velasco (1840-1912) was like a visual archaeologist, depicting the natural landscape and national spirit of Mexico from the dual perspectives of science and art. His works transcended the aesthetic function of traditional landscape paintings and became a symbol of the cultural revival after Mexico's independence. They were even printed on banknotes, stamps and textbooks, becoming the land memory in the hearts of local people. On March 29, the National Gallery of the United Kingdom will hold the exhibition "José María Velasco: Mexican Landscapes", which will showcase Velasco's artistic achievements with 30 paintings and sketches.

Before Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo developed and exported their 20th-century Mexican aesthetic, José María Velasco produced a body of landscape paintings that are widely considered essential to understanding Mexico.

Portrait of Jose Maria Velasco

Velasco was born into a restless world when Mexico had just ceded large tracts of land and faced invasion from the north. Orphaned as a child, Velasco grew up in poverty in Mexico City and eventually attended Mexico's first art school, where he was influenced by an Italian painter. "Velasco is not as well-known overseas as Rivera and Kahlo, but in Mexico his public status is similar to that of Constable or Turner in the UK," said Daniel Sobrino Ralston, co-curator of the exhibition. "He was not just a painter, he was also a generalist, engaging in geological, botanical and zoological observations and thinking, conducting in-depth studies of these local terrains and reflecting them in his paintings."

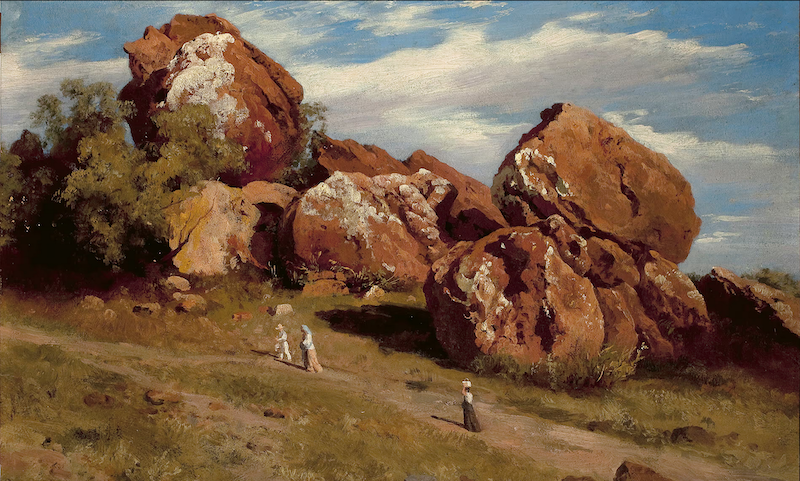

José María Velasco, The Rocks, 1894.

Velasco’s 1894 painting “Rocks” is a portrait in size and form, but the centerpiece is not a socialite in taffeta or tailcoats but a collection of giant reddish-brown rock formations—not a particularly special one, but the kind you’d encounter on any mountain walk.

That's the point. He was a scientific artist who lived in the age of discovery. He discovered a new species of salamander living in a lake near Mexico City. Of course, this was just one of many living fossils, or fossils, found in the New World during his time. In 1902, that's when the first Tyrannosaurus Rex fossil was unearthed in Montana; in 1909, well-preserved early life forms were found in the Burgess Shale in Canada. On top of that, back in the 1830s, Charles Darwin found the first evidence of evolution in the rainforests and rocks of Brazil and Peru.

Jose María Velasco, The Rocks of Atzacoalco

So behind the mundane rocks Velasco depicted was the discovery that the Earth’s structure was formed by continuous processes over millions of years, rather than by the catastrophes depicted in the Bible. The stones, Velasco said, held secrets worth knowing. The people in Rocks on the Hill of Atzacoalco, painted in 1874, look as if they were seeking such knowledge. They walk steadily down a path, the women in long skirts, the men in white suits, but the figures are dwarfed by the rocks, which are studded with white crystals that pierce like bone against the rust-red rock. Velasco was more interested in the rocks than in the people. Can’t you see how marvelous these ancient formations are, the work seems to ask?

The paintings shine with the light of the continent's ongoing development in time and space brought about by scientific discovery. In two spectacular panoramas of the Valley of Mexico, Velasco depicts snow-capped volcanoes floating above almost featureless, densely populated plains.

Jose María Velasco, "La Carolina Textile Factory"

Velasco, who trained in several sciences before choosing art, looks at the world between antiquity and change with an objective eye. His fascination with nature did not stop him from documenting Mexico's industrialization with the same curiosity. He incorporates not only traces of old and new human interventions in his paintings, but also symbols of Mexican culture and history. In his paintings, a shepherd tends his sheep next to a new factory, with the factory's shiny metal pipes and the light green leaves between which the shepherd shuttles are vividly depicted. Another work, titled "The Textile Mill of La Carolina," objectively depicts low white industrial buildings and a volcano behind them. Velasco's volcano is a satisfying cone, like a scientific toy, which only needs baking powder and vinegar to be added.

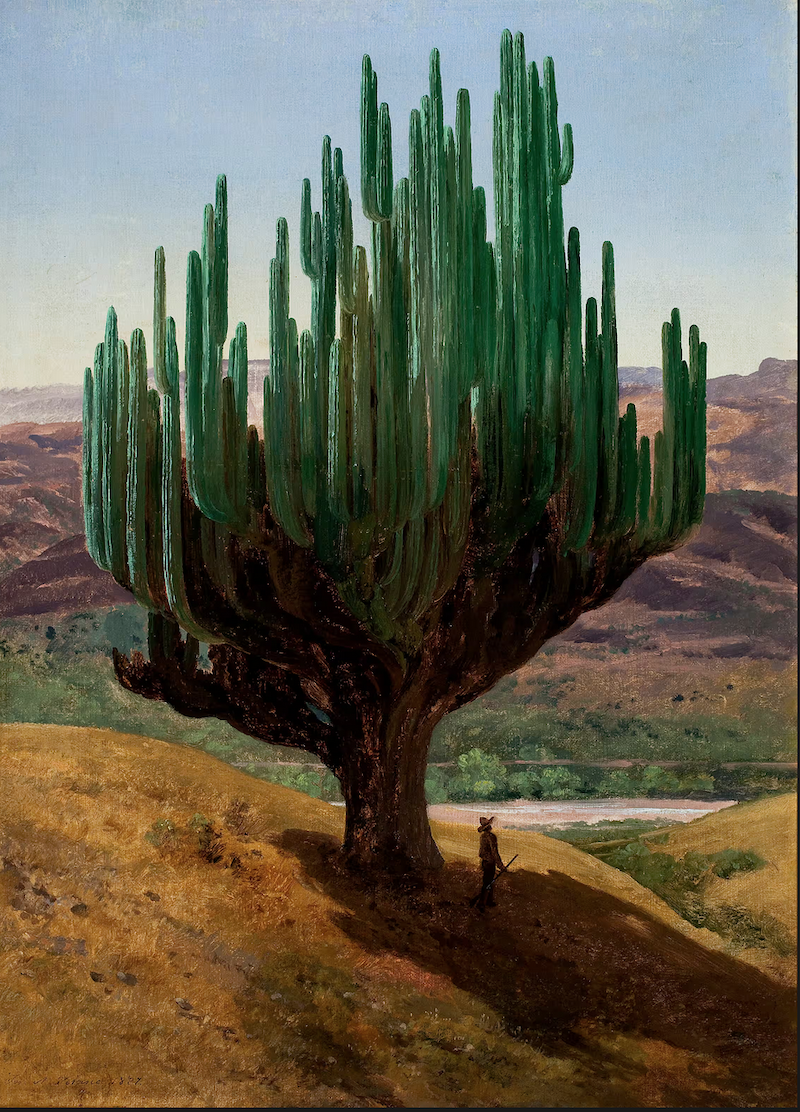

José María Velasco, Cadong, Oaxaca

His colors are delicate and clear, bringing out the blue-green tones of the leaves. His emerald cacti and the blue desert sky are haunting. His nature studies come to life. One painting, depicting thick, velvety maca leaves, is both a natural history and a passionate response to the green of nature. In the painting "Cadong, Oaxaca," a fantastic giant cactus is part of Velasco's lifelong dedication to Mexican flora. The tiny human figures in the painting not only give the viewer a sense of the scale of the plants, but also make people think about the relationship between man and nature.

José María Velasco, The Baths of King Nezahualcóyotl

If the landscape was brown or desert yellow, Velasco showed it. His 1878 painting, The Baths of King Nezahualcoyotl, was a non-romantic depiction of ancient ruins. Archaeology, he insisted, was about seeing the magic in the broken pieces, not Indiana Jones-style exploration. His precise depiction of this pre-Columbian site shows indecipherable masonry fragments and a flight of ancient steps.

Jose María Velasco, The Valley of Mexico from the Top of Santa Isabel Mountain

The Valley of Mexico from the Hill of Santa Isabel is considered Velasco's greatest artistic achievement, and it deftly blends different historical eras in an almost imperceptible way. In the foreground of the painting, there is a patch of prickly pear cactus and an eagle holding prey, the emblem in the center of the Mexican flag and also related to ancient mythology.

To say Velasco’s work is a bit dull would be a bit unkind. After all, his fluid brushstrokes resist the sublime effects that many other landscape artists in 19th-century America laid down with their painting trowels. For him, there is no such thing as the romantic transitions of Frederic Church, the Hudson River artist who depicted the eruption of Ecuador’s Cotopaxi volcano with a heavy metal concerto of fire. Geological structures are not there to shock us, Velasco says; they contain the scientific story of the Earth.

Beginning in 1876, during the repressive military regime of Porfirio Díaz, Velasco’s work was adopted by the state. While there is little evidence that he personally participated in political activity, his paintings were sent overseas and given as gifts by governments to American presidents and the pope. “The timing was perfect,” Ralston said. “Landscape painting was replacing history painting as a way for people to understand other countries. What was a country like? What were its resources? His work became the model for Mexico.”

Jose María Velasco, The Shepherd of San Angel

Ralston said Velasco's work is also instructive for studying 19th-century American landscape painting. "In contrast to American landscape painting, which shows an untouched wilderness without any history, he gives us a sense of a long, extensive history that goes back to ancient civilizations through plants and symbols and other elements. This is in stark contrast to this newly formed country to the north."

Velasco’s last great work was painted in 1910, the year of the Mexican Revolution and the sighting of Halley’s Comet. He depicted his own sighting of the comet in 1882, suggesting that Mexicans had seen comets before the Spanish arrived, linking a long history with great change.

Jose María Velasco, The Great Comet of 1882

Mexico’s visual history is the best tune. The Aztec Empire, on the eve of its conquest by Spain, used sacrifices, skulls, feathers, turquoise and jade to create artworks, and worshipped dangerous and disturbing gods. In modern Mexican art, from José Guadalupe Posada’s carnivalesque skull prints to Frida Kahlo’s personal expressions, these traditions have been enthusiastically embraced.

From heavy Mesoamerican totems to modern surrealism, there is no lack of attention for Mexican art. Outside the museum, there is Teresa Margolles's reproduction of the Aztec skull tower on the fourth pedestal. However, Velasco's work is different from these works of art. Because his vision is more European, academic and rationalist.

The exhibition will run from March 29 to August 17.

(This article is translated from The Guardian, and some content comes from the museum's official website)