"Creating Modernity: Art Treasures from the Musée d'Orsay in Paris" will open at the Pudong Art Museum on the afternoon of June 18. As the largest exhibition in the history of the Musée d'Orsay in China, "Creating Modernity" brings together more than 100 masterpieces of Western art from the 1840s to the early 20th century. Curator Stéphane Guegan is also the co-curator of "Treasures from the Musée d'Orsay in Paris" at the China Art Palace in Shanghai in 2012. In an exclusive interview with The Paper·Art Review, he said, "My primary criterion for selecting exhibits is 'excellence'. Some lesser-known works also reflect a very high artistic standard."

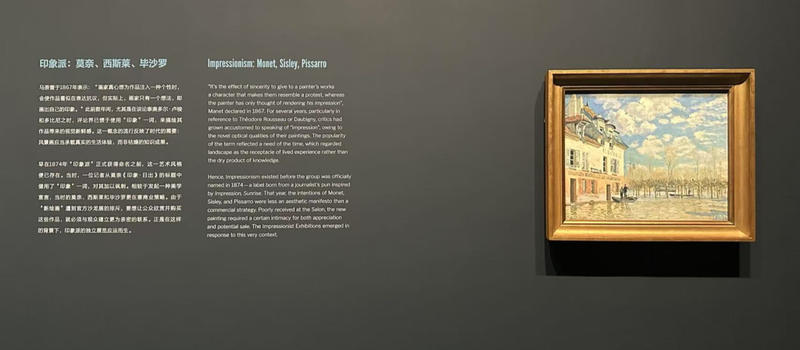

This is the first exhibition occupying two floors of the Pudong Art Museum since its opening in 2021. Here, "Impressionism" is included in an exhibition line starting from Jérôme and Cabanel and ending with Bonnard, looking at how artists and artists and the times are intertwined, respond to each other, and inspire each other.

In Stéphane Guegan's view, "Making Modern" is an exhibition that attempts to break the isolation of individuals and art schools. "I am interested in whether the audience who come to see Monet, Renoir, Sisley, Pissarro and Van Gogh can be surprised by other parts of the exhibition," Guegan said.

Exhibition site of “Creating Modernity: Art Treasures from the Musee d’Orsay in Paris”, Impressionism section, Manet and Degas section.

19th Century Art for Its Own Sake

The Paper: The exhibition opens with classical works by Jérôme and Cabanel, and the most recent work is Bonnard's "Toilette" from 1914. Why is the exhibition's time frame 1848-1914? Why are the two works the beginning and the end?

Guegan: It is true that in the second half of the 1840s there were still some artists known as academics who painted in a traditional way, but even these artists had the need to update their artistic language.

The first two works at the exhibition are Jean-Leon Gérôme's "Young Greeks Playing Cockfighting" 1846 (left) and Alexandre Cabanel's "The Birth of Venus" 1863 (right) Photo from The Paper

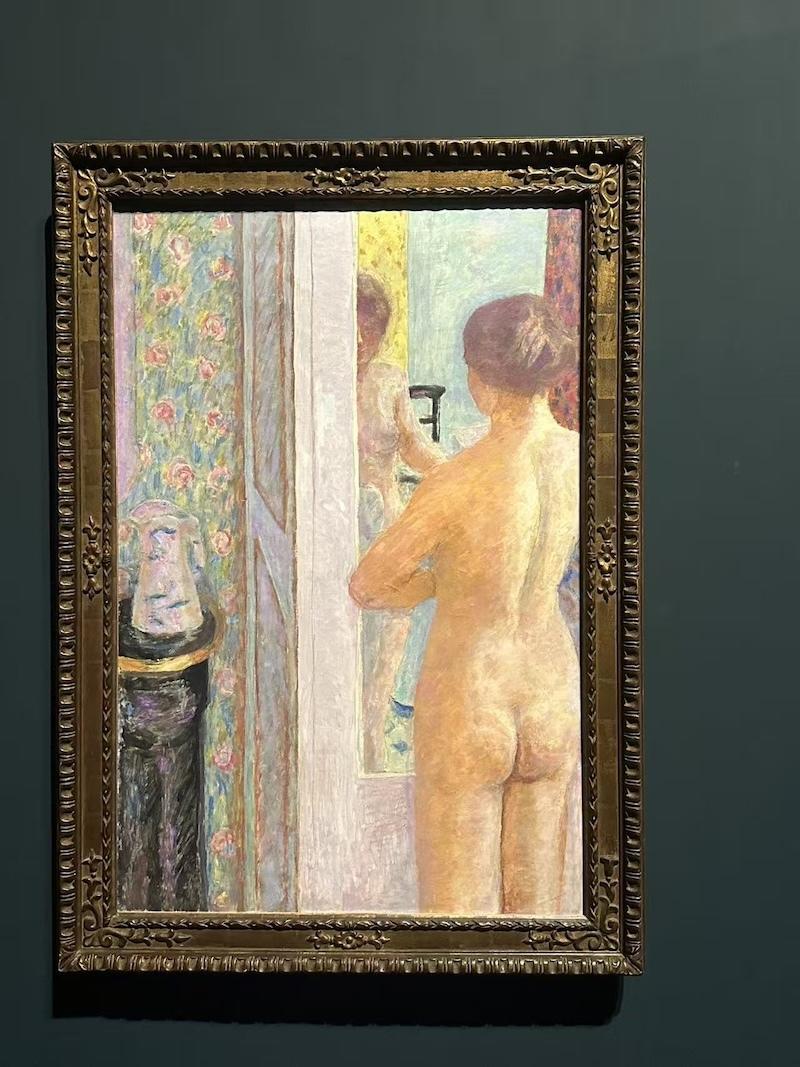

The exhibition opens with two nude paintings, a common subject in France at the time, and ends with a nude painting by Bonnard near the end of World War I. This also allows the audience to see the evolution of the subject of nudity in painting practice, from a highly idealized depiction of the nude to Bonnard's intimate (bathing-related) nudes, and finally to a more realistic expression.

The last work in the exhibition, Bonnard, "Toilet Paper", 1914

This time frame is used because this period is exactly the period covered by the collection of the Musee d'Orsay. The purpose of the Musee d'Orsay is to show art between 1848 and 1914. In France, everything is always closely related to politics. 1848 was a revolution ( Note: the February Revolution in France directly led to the revolutionary wave in Europe, which further hit the European coordination structure organized by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 ), and 1914 was a war ( World War I ). This exhibition echoes the social and political situation of this period on many levels, which is also the background experienced by the path of modernity.

Exhibition view, Ernest Meissonier, The Battle of France in 1814, 1864

The Paper: This exhibition is named “Creating Modernity”. How do you define the starting point of “modernity”?

Guegan: First of all, don’t confuse “modernity” with “modernism”. For us, the most important thing is to remind the audience that “modernity” is the artist’s ambition to show modern life. “Modernity” can be expressed in traditional ways or in very unique ways. At its core, the painter chooses to express the present in which they live.

I would also like to emphasize that I have never regarded 19th century art as a mere preview of the next century. For me, Cézanne is not the inventor of abstract art; Impressionism is not the creator of "themeless painting"; Manet is not the starting point for American painting in the 1950s. 19th century art should exist for its own sake.

The Paper: The exhibition brings together many core collections from the Orsay Museum. What criteria did you consider most during the selection process? From your perspective, which piece would you choose as the most valuable and meaningful?

Guegan: The first criterion is "excellence", but excellence does not necessarily mean that the work is considered a "masterpiece". Some lesser-known works also reflect a very high artistic level.

Another important criterion is to help Chinese audiences understand how the Musée d’Orsay established its own position. When it opened in 1986, the Musée d’Orsay was committed to interpreting works of art in a political and social context, paying attention to the evolution of historical context. In this exhibition, we strive to reproduce this methodology, whether it is the ideological connection between Courbet and Proudhon (1809-1865, French socialist, politician, philosopher, economist, and founder of mutualism philosophy), or the parallel between Manet and Zola, or the "Nabis" at the end of the exhibition - they not only see themselves as pioneers in aesthetics, but also as "prophets" in the social and political fields.

The final chapter of the exhibition is about the "Nabis".

As for which work is the most valuable and meaningful, judging from the exhibition design and my feelings when visiting the exhibition these days, I would say it is Van Gogh's "Bedroom", and this answer may seem a bit "expected". The painting is surrounded by important friends and artists in his life: Gauguin, Signac, Emile Bernard, and his most admired predecessor Millet. This bedroom may be just a room in a country cottage, but it seems to respond to all artistic and humanistic concerns of the entire 19th century.

Exhibition site, Van Gogh's "Room" and Gauguin's works

The 2012 “Miller, Courbet” exhibition at the Orsay and Shanghai was curated by the same person

The Paper: In 2012, the exhibition "Miller, Courbet and French Naturalism: Treasures from the Musee d'Orsay in Paris" (November 16, 2012 - February 28, 2013) was held. At that time, Millet's "The Gleaners" was first exhibited in China. More than a decade later, it was exhibited again in Shanghai. What is the difference between the exhibition's narrative style and the previous ones? As a realist artist, what role did he play in the birth of modernism?

Guegan: It’s a very beautiful work, and it takes on a slightly different meaning in this exhibition, which I also curated, Millet, Courbet and French Naturalism, which focused on the Realist movement and its evolution.

On November 16, 2012, visitors admired the famous painting "The Gleaners" at the exhibition "Miller, Courbet and French Naturalism: Treasures from the Musee d'Orsay in Paris"

In this exhibition, we hope to show that Miller also belongs to another period of art history.

That's why I emphasize Van Gogh's frequent citations. Van Gogh not only mentions Millet in his letters, but also quotes him in his works. Many of Van Gogh's works are directly inspired by Millet's prints. He "translated" these prints, in a sense, a translation of the visual language. So what we want to show is that Millet certainly belongs to the Realist movement, but he also continues to have an influence later, especially for artists who focus on traditional society.

The Gleaners at the exhibition “Creating Modernity: Art Treasures from the Musee d’Orsay in Paris”

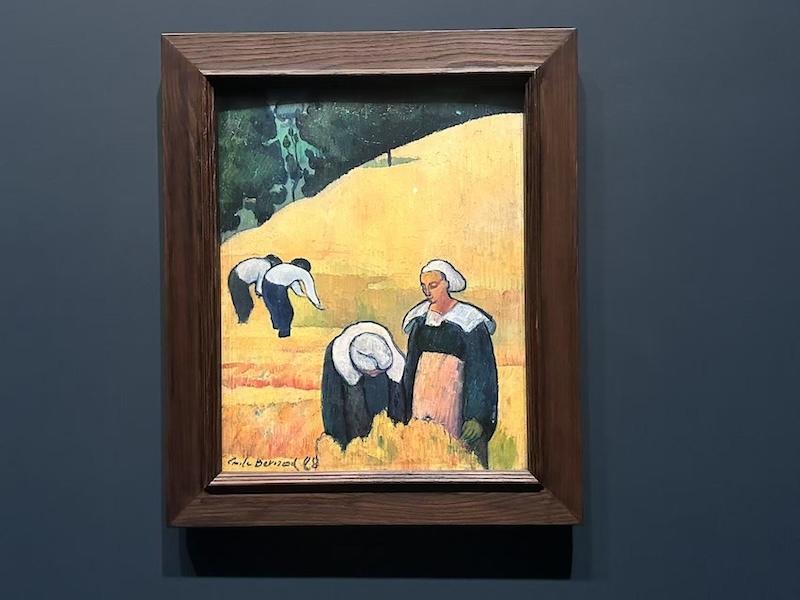

What these artists portrayed was not so much modern life as rural life. By depicting rural life, they were praising another set of values, another group of virtues and customs, including a certain attachment to religion.

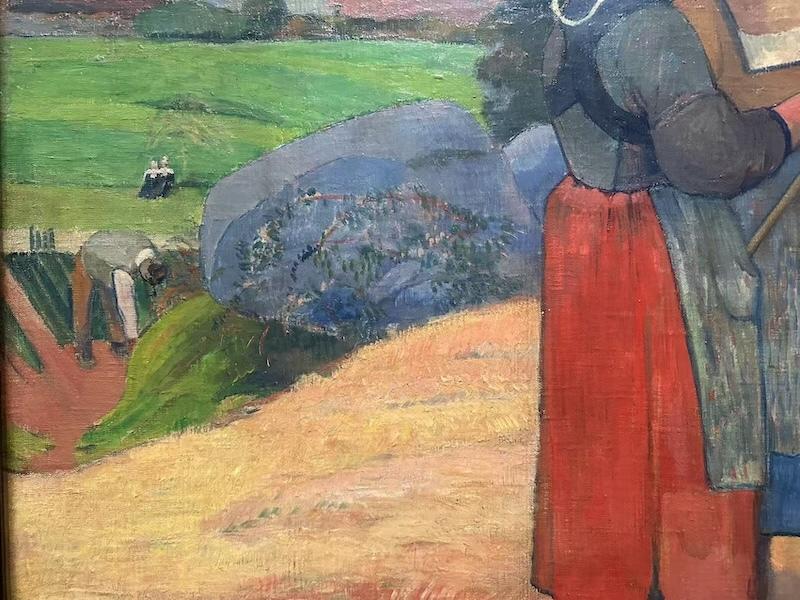

Exhibition view, Emile Bernard, The Wheat Harvest, 1888

So we can say that Millet is in a critical middle position. He witnessed and participated in the rise of realism, but at the same time, he subtly influenced later artists. Therefore, the way we look at Millet today is different from 13 years ago - he is not only himself, but also the "sower" in French painting, bringing inspiration and nourishment to later artists.

Miller's The Gleaners (detail)

Paul Gauguin, A Peasant Woman in Brittany (detail), 1894

The Paper: Since that year's exhibition, Shanghai's art galleries and exhibitions have become more diverse. What are the differences in your experience of curating exhibitions for Shanghai twice?

Gaygan: That year has fond memories for many reasons.

First, because I felt the passion for these paintings—a passion I had known about before, but I felt and measured its depth that time. During the 2012 exhibition, I walked through the gallery while the public was visiting and felt the passion that these works inspired in the audience.

I am also most impressed by the older generation of artists I met, who were trained in the 1950s or 1960s and who had a deep love for Millet, Bastien Lepage, and Léon Augustin Lhermitte.

"Creating Modernity: Art Treasures from the Musee d'Orsay in Paris" exhibition site

I was like, “This is just like listening to Van Gogh.” Because when Van Gogh talked about these painters, he got really emotional and he couldn’t control himself.

We in France have long known that the realistic tradition of Chinese painting in the 20th century largely continued certain French paradigms. This time, I witnessed and felt this in person.

That time, we also brought The Gleaners (a work that had never left the walls of the Orsay before), as well as some works hidden deep in the warehouse, to be presented in Shanghai that year. I deeply realized that our curatorial concept really resonated with the expectations of the public (both artists and ordinary audiences), and they responded strongly to these works.

Exhibition view of "Miller, Courbet and French Naturalism" in 2012

It has been 12 years since that exhibition. The city has obviously undergone tremendous changes. Shanghai's art museum system has become richer, more professional and more international. The city now organizes more and more exhibitions, introduces more and more projects, and has more international partners. The overall aesthetic and professional requirements of citizens have been significantly improved in the past 12 years, or in other words, they are more "picky" than in the past.

Moreover, we have been through a lot in recent years—the world has experienced various disasters, such as public health crises and wars. I felt that at that exhibition 12 years ago, we were still "living" in the 20th century. That's why I was deeply moved by the appearance of those older generation artists.

Today, we have truly entered the 21st century - a century full of anxiety about climate change, war and economic conflict. I feel that in this context, people may have different feelings when looking at some of the paintings in this exhibition, especially those by artists who have always depicted rural life, different lifestyles and methods of production.

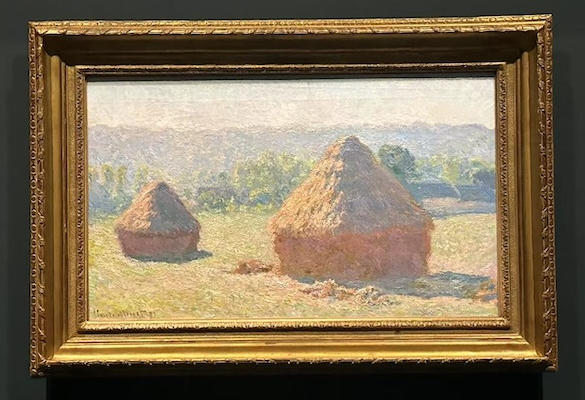

Exhibition view, Monet, Haystacks, Late Summer, 1891

The Paper: Impressionist works always cause a sensation when they are exhibited in Shanghai. The "French Impressionist Painting Treasures Exhibition" in 2004, also from the Orsay, is still vividly remembered. Why are Impressionist works still loved by audiences in Shanghai and around the world?

Guegan: I would like to ask you why Shanghai audiences like Impressionism (laughs), but I feel very gratified.

It seems to me that a new generation of French audiences is slowly turning away from Impressionism and focusing more on 20th century art, especially photography.

As one of the older curators of the Musee d'Orsay, I still remember that nearly 40 years ago, Impressionism felt very close to us. But as time goes by, we are getting further and further away from the century of Impressionism, so today we look at Impressionism with a new perspective, perhaps seeing it as a more "fragile" moment, a legacy that needs to be protected.

Exhibition view, Sisley's "Boats in the Flood at Port Marly" 1876

However, I think the public is still moved by the "freshness". Those painters tried to capture the rhythm of the world, the fluidity of their gaze. And their works still retain their spontaneity, vitality and vibrating energy.

There is also a sense that these paintings represent a kind of “golden age” of life – a world in which people could enjoy the pleasures of being together in the green areas outside Paris, or on the beaches of Normandy or Brittany without reservation. It was a world that had not yet been disturbed by modern life.

Exhibition view, Manet's "On the Beach" 1873

Of course, we also know that this is an illusion - because France was already experiencing the Industrial Revolution at that time, and the natural landscape and the surrounding areas of the city were undergoing drastic changes. So this is indeed an illusion, but it is an intoxicating illusion that prompts us to reflect on the future.

Therefore, viewers are moved by these paintings not only because of their own appeal, but also because they evoke our thoughts about an era.

Impressionist painters who appeared in groups

The Paper: The Impressionist section, which attracted the most attention in the exhibition, is grouped into twos and threes, such as Manet and Degas, Monet, Sisley, and Pissarro, Renoir and Cézanne, Gauguin and Van Gogh, etc. How was this grouping achieved?

Guegan: I really like this juxtaposition and contrast between artists, and I like to tell the story of their "friendship".

Because I think that painting from the 19th century to the 1950s and 1960s was essentially a collective practice. Artists formed groups, discussed together, and inspired each other. This was an almost "associative" way of thinking.

The first exhibition of what we now call "Impressionism" (the famous exhibition in 1874) was actually a kind of "artists' association": not only painters, but also sculptors, who wanted to break away from the norms of the official salon and find their own exhibition mechanism.

It could be said that the art world of the 19th century was all about “association”, about bringing together ideas, energies and perspectives. I believe this exhibition captures this dynamic of “collective creation” very well.

Exhibition site, Manet and the Plate

Back to the pair of Manet and Degas. I curated an exhibition on them at the Musee d'Orsay two years ago. The reason for putting them together is that they often deal with similar themes.

Exhibition view of “Manet: Degas” at the Musee d’Orsay in France.

Degas once tried to invite Manet to join the Impressionist exhibition system, although it was ultimately unsuccessful. However, he admired Manet very much and even collected Manet's works.

They all attach great importance to the expression of "human images" and are not satisfied with landscape or still life paintings. This is actually a very "traditional" insistence: characters, psychological states, social reality - the profundity of these themes connects them together.

And we’ve included their friends in the gallery. For example, James Tissot, who knew Manet well and was also close to Degas—he even traveled to Venice with Manet. And then there’s Stéphanes, who has a really great painting in the show, who was a close friend of Baudelaire and also knew Manet.

Exhibition view, Stevens's "Bath" circa 1873

Therefore, this is not only a dialogue between two artists, but also a portrayal of the collective practice and ideological confrontation between painters of the entire era. We also hope to make this network-like connection emerge through these "combinations".

The Paper: You mentioned that "Manet and Zola go hand in hand." In this exhibition, there is a painting of Zola by Manet, which also contains many elements. How do you interpret this work and their friendship?

Guegan: This is a symbol of friendship. In 1866, Zola spoke out for Manet, who was rejected from the Salon, especially for his famous work, The Flute Boy, which was later stored in the Orsay. In the same year, Zola published an article to defend him. In 1867, during the World Exhibition, Zola published another long article to defend Manet.

Zola admired Manet for his sincerity, clarity and realism. He felt a deep affinity between his ideas in fiction and those in painting. The following year, Manet presented this portrait to Zola as a token of his gratitude.

At the exhibition, Manet painted a portrait of Zola.

The painting is both a portrait of Zola and an allegory, not only of their friendship but also of their aesthetic struggle. The word "struggle" is actually very common in Zola's writing - this is how he understood the profession of journalist: a struggle. Therefore, in addition to depicting Zola himself, the painting also conveys his spiritual outlook as a writer. For example, the painting depicts his broad and bright forehead, as if to emphasize his keen analytical ability and strong creativity.

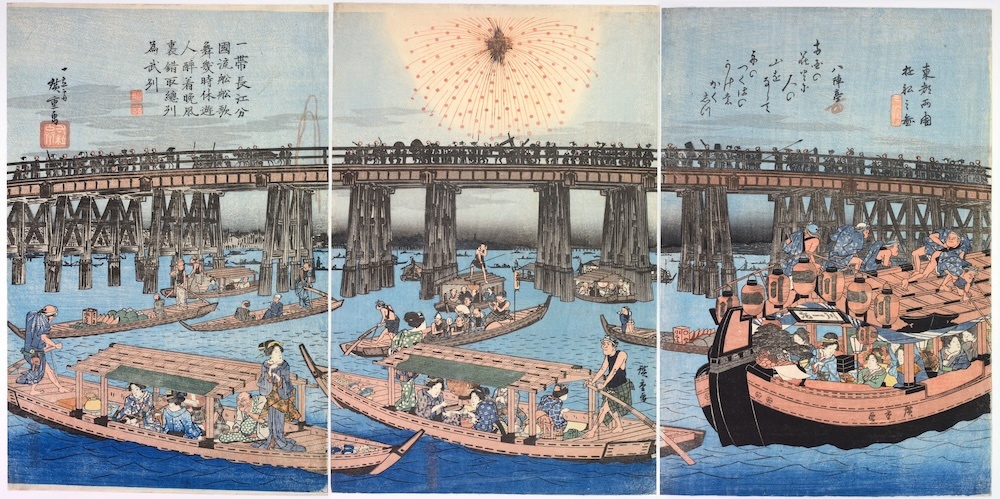

In addition, at the top of the picture, we can see several details: a Japanese ukiyo-e, a print adapted from Velázquez, and a gray sketch recalling "Olympia".

Manet, Emile Zola (detail), 1868

So, this painting is also a symbol, symbolizing their aesthetic stance and common struggle - that is, French realism draws inspiration from Spanish art on the one hand, and is also influenced by Oriental painting on the other.

The Paper: Compared to the “Manet /Degas ” exhibition at the Musee d’Orsay in 2023, which you curated, what are the similarities and differences between this “Manet, Degas” section?

Guegan: In the exhibition “Manet/Degas” we naturally focused on themes that the two had worked on together. This also excluded certain classic subjects, such as Degas’s “Dancers” series, because there were almost no corresponding subjects in Manet’s work.

Exhibition view of “Manet: Degas” at the Musee d’Orsay in France.

I was very eager to present Degas’ sculptures in the exhibition hall, but it was not possible. Now in Shanghai, sculptures and paintings are displayed side by side, and the arrangement is particularly beautiful. These sculptures not only enrich the visual experience, but also remind us that Degas and Manet both have a strong obsession with how to capture "movement". They are not satisfied with static reproduction, but try to make time flow and things change through painting. They want the static medium of painting to convey the vitality and changes of life itself.

Exhibition site, Degas' sculptures and paintings

The Paper: As you said, in addition to the dialogue between artists, this exhibition will also juxtapose paintings and sculptures with similar artistic explorations. How do you create a dialogue between painting and sculpture? What was the relationship between painting and sculpture at that time?

Guegan: In the comparison between Degas and Manet, as far as I know, Manet never dabbled in sculpture, while Degas had a very deep practice in sculpture. After his death, a large number of sculptures were found in his studio, which were later cast in bronze. Although most of these bronzes were cast after his death, sculpture itself was an important dimension of his artistic thinking.

Exhibition site, Rodin's sculpture

I was also very interested in other sculptures in the exhibition, such as some portraits by Rodin and the Princess Mathilde by Carpeaux. In this exhibition, we also tried to evoke the "Spirit of the Orsay". One of the most representative characteristics of the Musee d'Orsay is that it broke through the limitations of traditional art galleries divided by media and brought together different media such as painting, sculpture, photography and even film. This was a very unique attempt at the time.

The sculpture of Princess Mathilde created by Carpeaux at the exhibition

Of course, there are also some artists who originally practiced cross-media. For example, Gauguin was also an important sculptor. When he participated in the Impressionist exhibition in the early days, he exhibited sculptures, some of which even had a certain classical temperament.

Later, his stay in Polynesia exposed him to a completely different sculptural tradition. Through wood carvings (two of which are on display in the exhibition), he tried to absorb and integrate local culture, especially Maori culture, which is almost extinct but still survives in the form of certain small objects. He became fascinated by the patterns, ornaments, and even small religious stelae on these objects.

Exhibition site, Gauguin's sculpture

Gauguin tried to rebuild a complete worldview from these "cultural remnants". The "direct engraving" method he adopted also became a means for him to break through the established language of painting and seek self-innovation - a path to another world.

The Nabis also included some sculptors, such as Maillol, and even Vallotton himself had tried clay sculpture. Therefore, the appearance of sculpture in the last exhibition hall of the exhibition is closely related to the Nabis' attention to this art form.

The exhibition site, Vallotton's sculpture "Woman Holding Up Her Nightdress"

So I think we should not isolate different artistic practices, nor should we treat individual artists separately.

The 19th century was actually an era that advocated integration and was keen on establishing connections between different fields and media. The purpose of our exhibition is not only to display the works themselves, but also to create an atmosphere and a possible way of narrating art history. In such a conception, sculpture should undoubtedly occupy a place, and it is an important part of the exhibition expression.

In addition to masterpieces, we should also pay attention to the transition and resonance between art forms

The Paper: In addition to the artists and works that have been repeatedly written about in art history, which artists or works in the exhibition are generally less noticed but are meaningful in the development of Western art?

Guegan: I think that the work of painters like Gérôme and Cabanel is not well known today, even though they were much more famous than the Impressionists in the 19th century. But I think of a few things, especially the "Portrait of Jules Bittan" by Ernest Didier—a scene of a painter painting by the sea, with a horse tied to him, painting in nature.

Exhibition view, Ernest Die, “Jules Bittan”, 1880

I find it interesting that Dié is now almost forgotten and ignored by art history, as he was not an "official" artist within the system, but he was never involved in real avant-garde circles, and instead developed his career mainly within the Salon system.

Yet, Douez was a close associate of Manet, and here he depicts a painter whose image is emblematic of the transformation of “outdoor painting,” a practice that originated in the avant-garde, into mainstream painting and was eventually accepted by salons and academies.

Dié's "Julis Bitin" was also exhibited in Shanghai in 2012.

So, through this portrait, I want to remind everyone that an art form that was once considered radical or subversive often goes through a path from the margins to the center. At first, it may be criticized and rejected, but eventually it becomes the standard and the norm.

"Outdoor sketching" is a typical example of this - it was initially practiced only in avant-garde circles, but eventually became a norm and common method in the entire art world.

The Paper: In the division of the exhibition into five units, do you prefer to emphasize the progressive evolution of artistic styles, or the modern appearance of multiple parallel and intertwined development? How do you guide the audience to look back at the times through the composition and brushstrokes of the paintings?

Guegan: When we curated this exhibition, our hope was to encourage visitors to rethink the meaning of "modernity". I would be very happy if every visitor could say to themselves when they left the exhibition hall: "I thought this exhibition was just about Impressionism and its direct depiction of modern life, but I didn't expect it to lead me to some unexpected contrasts, connections, and even new perspectives."

Exhibition View

I intentionally "reshuffled the cards" to show that the development of art is not linear, but more complex and subtle. It is often based on exchanges and flows, and sometimes even hidden connections. Some connections and resonances between generations and artists that we have forgotten actually still exist. And those clear "opposites" in history are often too rigid constructions.

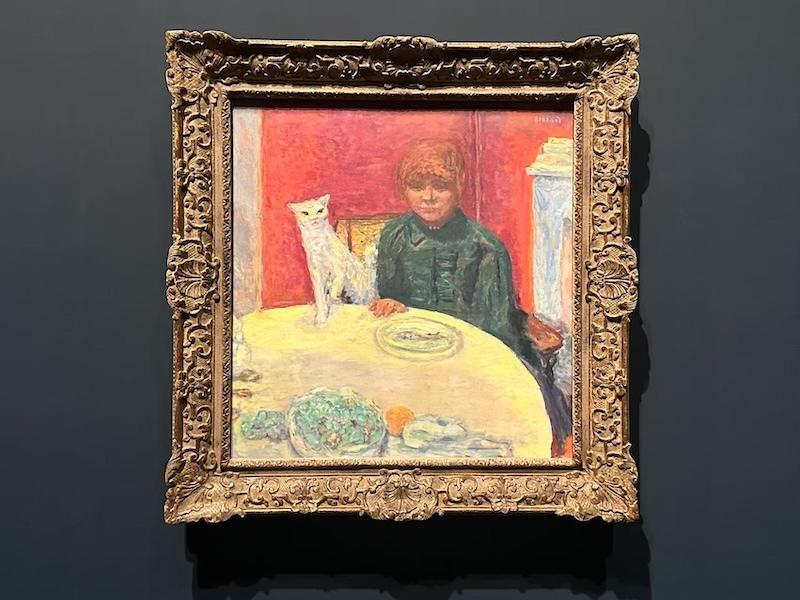

What this exhibition wants to do is to make the boundaries softer and break down certain barriers. I am very interested in the Nabis and have written a book about Bonnard. They put forward an important proposition: art should not be divided into categories. An artist can create paintings, sculptures, and design fabrics and furniture at the same time.

Exhibition site, Bonnard "Woman with Cat" circa 1912

I was inspired by this idea and tried to break the overly rigid narrative of art history in this exhibition. What we need to do is to present the transition and resonance between art. Of course, each generation of artists will bring something new, but if we are willing to observe carefully, we will find that the development of art has never been interrupted - there are always continuous clues, resonances, and tenacious extension and regeneration.

In my opinion, this way of understanding is perhaps more relevant to our present situation than ever before.

- fNEGynakvsNoHa06/18/2025

- YwqTNNwkpLoYnT06/18/2025

- USvGGwrHBb06/18/2025