Are paintings enriched by our understanding of the circumstances in which they were created? The answer is yes.

"Eccentric and timid, he was a man consumed by self-doubt," Monet once said of Paul Cézanne, while his childhood friend Zola called him "a sphinx." Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), known as the "Father of Modern Art," is currently on display at the Shanghai Pudong Art Museum. His hometown, Aix-en-Provence in southern France, has become a focal point for art pilgrimages this summer. The reopened Château Jas de Buffon and the distant Mont Sainte-Victoire have become key destinations for those seeking Cézanne.

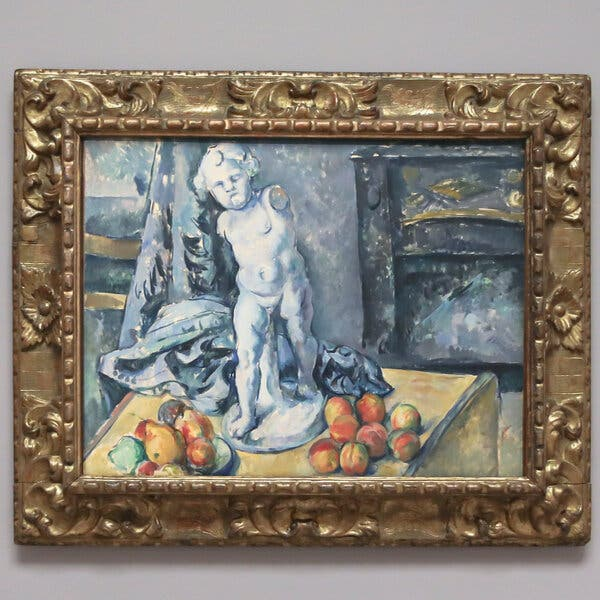

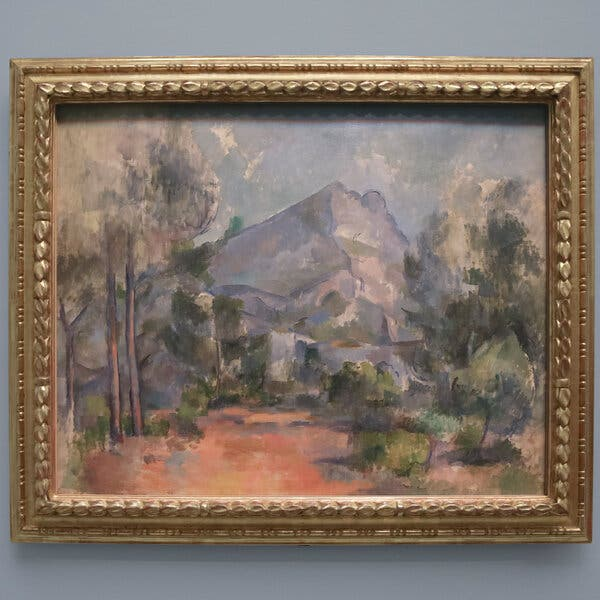

Cézanne's work depicting Mont Sainte-Victoire and the town in the foreground.

Paul Cézanne, “Rocks near the Cave above the Castle Black,” circa 1904 (Exhibition view at the Pudong Art Museum)

Cézanne lived with a constant hesitation, and his paintings echo this – a hesitation so deliberate in his brushstrokes that it seems to actively destroy the possibility of objective representation. For Braque, Picasso, Duchamp, and other 20th-century artists concerned with the question of relativity, Cézanne was a "skeptical prophet."

This summer, he's the focal point of a European art pilgrimage. To better understand Cézanne, art lovers are flocking to Aix-en-Provence in southern France, his hometown, to participate in "Cézanne 2025," a regional cultural event spanning summer and autumn, featuring a rich program of exhibitions and public programs.

Cézanne in his studio in the Aix-en-Provence district in 1905.

The centerpiece of the event is “Cézanne at Jas de Bouffan,” a meticulously curated retrospective showcasing some 130 of Cézanne’s works, most on loan, at the Musée Granet, the former drawing school where Cézanne trained early in his career. The exhibition coincides with the (partial) reopening of his family’s country house.

The Granet Museum's exhibition "Cézanne at Jas de Buffon"

A series of activities have brought crowds of people to the town, and the shops and galleries in the town have launched a large number of derivative products. For tourists, it is like a treasure hunt game - traveling between the works in the art gallery and the life footprints of Provençal painters.

For art researchers, a more worthy question is: Will paintings become richer if we understand the environment in which they were created?

The answer given by the Granet Museum exhibition is: yes.

Cézanne was born in 1839 in the heart of Aix-en-Provence's old town. He spent his childhood in various houses along the city's narrow streets. At the age of 13, he met the writer Émile Zola at the Lycée Bourbon (now Lycée de Migné), with whom he became close friends. His father, Louis-Auguste, was a hat maker who made his fortune selling rabbit furs (a major industry in Aix at the time) and later expanded his wealth by investing in banking.

When Cézanne was 20, his father bought the estate of Jas de Bouffon as a country villa. From then until 1899, it became the center of Cézanne's world.

Cézanne's first studio was located on the top floor of the Jas de Bouffan mansion, the former home of his family.

In his twenties, Cézanne was allowed to paint murals in the hall of his father's newly acquired country house: romantic landscapes and allegorical figures, often inspired by famous French etchings. In the early 20th century, the house's next owner cut the murals from the walls before renovating them, but most of them have been carefully preserved and loaned for this exhibition.

Paul Cézanne, House and Cottage at Jas de Buffon, 1885–1887

Today, as you enter this stately, symmetrical mansion from the cacophony of cicadas outside, the hall suddenly descends into a cathedral-like silence. A semicircular niche surrounds the wall, where faint traces of Cézanne's paintings can still be seen. Once hung here, tall murals depicting the four seasons, painted in a style with a slightly folk-romantic flatness. Today, these paintings are all signed "Ingres" and are on display at the Granet Museum. These signatures, seemingly a nod to the masters of the French Academic school, have long been viewed by critics as a satirical play on tradition by Cézanne.

But “Ingres may not be a joke,” said Bruno Ely, director of the Granet Museum, as we gazed together at four seasonal paintings reunited from museums around the world. “Seeing these tributes to Ingres surrounding the elder Cézanne, he would have felt that his son was both affirming his own artistic choices and giving dignity and value to the home he decorated.”

They “surround” the painting that originally occupied the center of the niche (now also “reunited” at the Granet Museum): a portrait of his father, created around 1865. In the painting, Louis-Auguste Cézanne is reading, his expression serious but not without dignity.

Cézanne feared his father his entire life. For years, he concealed his lover and illegitimate child for fear his father would cut off his financial support. But now, when the portrait is returned to its original setting—surrounded by classical allegorical paintings—this arrangement casts doubt on the "resentful" father-son relationship portrayed by many writers.

It makes people think: Perhaps Cézanne's feelings towards his father were not just repression and hostility, but also included respect, struggle and a complex and profound identification.

A portrait of Cézanne's father reading, displayed in the Musée Granet alongside his earlier decorative works.

This portrait of his father was created during what Cézanne called his "couillarde period" (literally, "full of courage"), a period of bold, heavy, and wild brushstrokes. However, it was precisely because of this reckless expression that he was repeatedly rejected from the Paris Salon.

In the fragments of murals exhibited in the Granet Museum, beneath the swift and rough style, one can vaguely see the sunset tones and gentle brushstrokes of his early landscape paintings - these are the layers of evolution of his painting style.

By the 1870s, under Pissarro’s guidance, Cézanne underwent another transformation, gradually transitioning from a harsh, untamed style to a more transparent and airy Impressionist style. Several sketches from Jas de Buffon’s estate, displayed side by side in the exhibition, clearly illustrate this shift.

When strolling through this estate on the west side of Aix, you will have a wonderful feeling of "walking into a painting": the pond reflecting the sky, the warm ochre walls - these scenes have all appeared in his works, and when you see them one by one, it is as if you are walking on Cézanne's palette.

A pond in the gardens of Jas de Bouffon's estate.

But for Cézanne, the "what" of his paintings was far less important than the "how." He was a slow and persistent artist: a single portrait could consume hundreds of hours, sometimes pausing for a full 15 minutes before each stroke. He rejected the performative "improvisational" nature of Impressionism, instead cultivating his unique, mature style through deliberate distortions of perspective.

Gazing at the canvases depicting fruit and utensils, you can almost sense these objects being repeatedly observed and pondered at different times and from different perspectives, to the point of near neurotic obsession. Apples became his preferred subject—because they decay the slowest, giving him plenty of time to paint them.

Paul Cézanne’s “Still Life with Plaster Cupid” (1894–1895). This plaster figure of Cupid appears in several paintings in the Granet Museum exhibition.

After his mother's death in 1897, Cézanne's family sold the house where he had lived and painted for so long. He moved into an apartment in the city center and built a separate studio on a hillside in the Lauves district north of the city, which he used until his death in 1906.

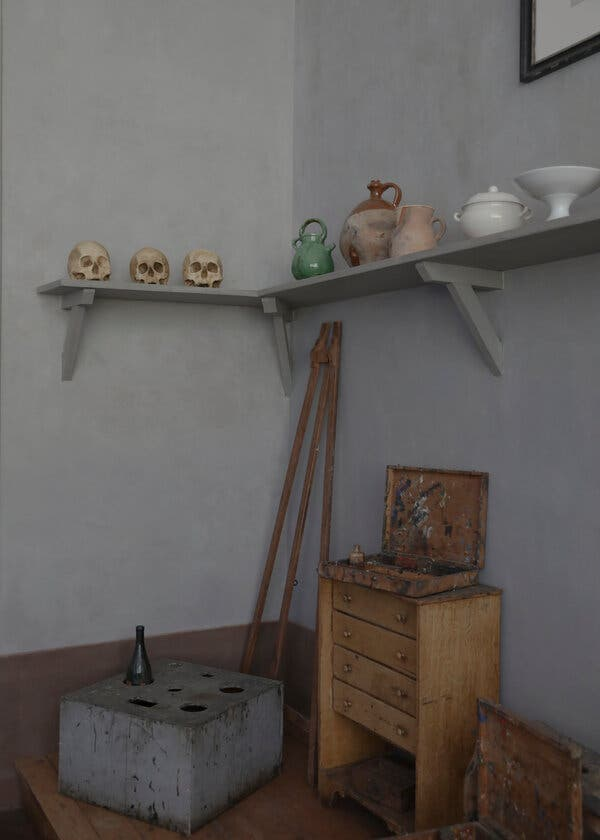

Interior view of Cézanne's studio in the Aix-en-Provence district.

The studio was rescued from the real estate market last century after a series of twists and turns, including the involvement of a private American donor. It has now been restored and reopened. The interior still boasts the familiar north-facing natural light and meticulously blended gray walls, and the protagonists of Cézanne's paintings still await: ceramic ginger jars, glazed vessels, a rum bottle wrapped in straw netting, and the Cupid figure—whose stylistic evolution can be seen in several paintings at the Granet Museum.

Cézanne's personal belongings and painting tools kept in his studio in the Loire district of Aix-en-Provence.

You'll notice that Cézanne exaggerated the size of Cupid in his painting. But if Cézanne taught us anything, it's that "the height seen by the eye is the height felt by the heart."

The closer you observe in Cézanne’s carefully controlled environment, the more you realize that all his experiments are actually against “deterministic cognition.” In his writing, reality is no longer an object that can be measured and defined, but an experience that flows between time, feeling and space.

The studio is bathed in natural light from large north-facing windows throughout the day.

The main visual image of "Cézanne 2025" is the black-and-white photo of Cézanne gazing at the age of 33. However, the image has been "beautified" and the face has been modified to be softer and warmer. This approach seems a bit weird and even incompatible with the rational and pure spiritual temperament in Cézanne's works.

A retouched photograph of Cézanne taken in 1872

To make matters worse, the local government, despite its constant talk of Cézanne's "homecoming," has just approved a massive development project at the foot of Mont Sainte-Victoire, the subject of dozens of Cézanne's seminal landscapes. The Mont Sainte-Victoire series offers a meditation on a timeless theme, but when the real Mont Sainte-Victoire is surrounded by a vast urban periphery, can these paintings truly transcend mere "documentary" status?

Mont Sainte-Victoire (1897) depicts one of Cézanne’s most famous local peaks, a subject he painted in dozens of seminal works.

Recently, on Mont-Louve, not far from Cézanne's studio, pilgrims from all over the world took photos, and one could almost sense a mood of mourning, prepared for a rainy day. Mont-Sainte-Victoire still stands majestically, overlooking the town, just as Cézanne described it when he was 67 years old—a strange double silhouette, gray-blue by day, tinged with rose-gold at dusk, like a silent sphinx.

A view of Mount Sainte-Victoire, near Cézanne's studio. The local government has approved development at the foot of the mountain.

- kCTBCtdxd07/30/2025

- FvlQhKOk07/30/2025

- YYRgYQIlLF07/30/2025