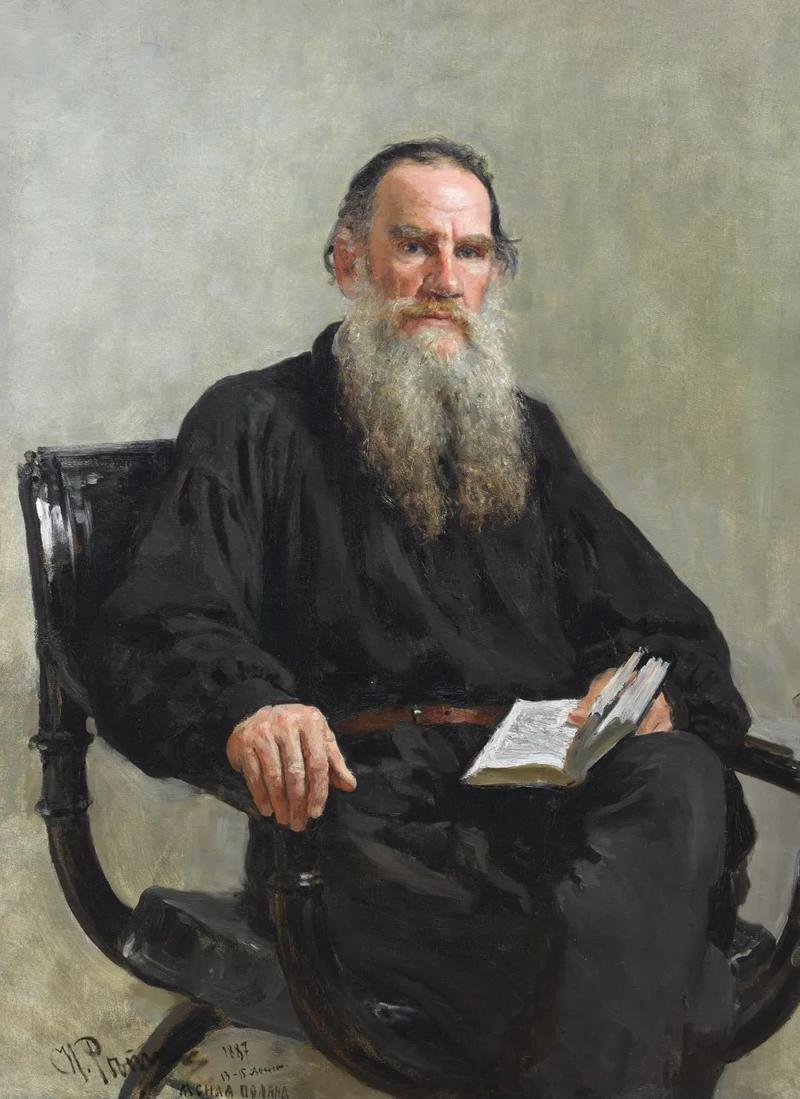

At the National Museum's "Reveries on the Neva: A Special Exhibition of Repin's Art," a seemingly simple portrait often draws crowds. In it, Leo Tolstoy, draped in a black robe and with a snow-white beard, his gray eyes, piercing the canvas, seem to ponder profound human questions. This is Repin's masterpiece, a psychological portrait of Tolstoy, created in the summer of 1887. The painting bears witness not only to the three-decade friendship between the two masters but also to a golden age of Russian literature.

At the National Museum's "Reveries on the Neva River - Repin Art Exhibition", a visitor pauses in front of "Portrait of Leo Tolstoy".

This painting, titled "Portrait of Leo Tolstoy," was completed by Repin in just three days. Its strikingly simple composition conveys the author's rich inner world. The gray and black tones contrast with the red face and those "sparkling eyes," making the viewer feel as if "those gray pupils would suddenly turn, and the lips tightly pursed beneath the snow-white beard would begin to speak." Repin abandoned all ostentatious embellishments, using the sturdy hands of a peasant and the dark brown leather belt bounding his black robe to capture Tolstoy's dual nature as a thinker and a doer of action—it is this essence that makes this portrait a visual symbol of the Russian national spirit.

Ilya Repin, Portrait of Leo Tolstoy, 1887, oil on canvas, 124 cm x 88 cm, Tretyakov Gallery

The spiritual resonance between masters

In 1880, when the 36-year-old Repin first entered the 52-year-old Tolstoy's house in Khamovniki, Moscow, a profound dialogue across the realms of art and literature began. With his meticulous painter's eye, Repin "scanned Tolstoy from head to toe," then captured the literary master's vivid image in equally captivating prose: "Is Leo Tolstoy really like this? So he is such a man!... His head is not as big as I imagined." This encounter launched a rare thirty-year friendship in art history, with the two men visiting each other, exchanging letters, exchanging ideas, and engaging in passionate debates on the nature of art and social responsibility along the forest paths of their Yasnaya Polyana estate.

Ilya Repin, Tolstoy in the Forest, Tretyakov Gallery

Ilya Repin, Tolstoy in his study, from the collection of the Russian State Literary Museum

Repin's series of paintings depicting Tolstoy constitute one of the most comprehensive records of the artist's soul in world art history: throughout his life, he created twelve portraits, twenty-five sketches, eight drawings of Tolstoy's family members, seventeen illustrations of his works, and three plaster statues. These works transcend the solemn framework of traditional portraiture, capturing the literary giant's vibrant human presence: from Tolstoy plowing the fields, writing, sitting on a bench, or on his sickbed, Repin's brush was "unpretentious," "clearing away all impetuousness and distractions" in nature.

Ilya Repin, Leo Tolstoy at Work, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, 1887

On a sweltering August day in 1887, Repin witnessed a deeply moving scene: Tolstoy plowing the black earth of his Yasnaya Polyana estate for six hours straight. The artist quickly opened his sketchbook, "snatching every detail as the entire procession—horse, plow, Tolstoy, horse, and harrow—passed before him." Born from this observation, "Leo Tolstoy at Work" became one of the most unique portraits of a man of letters in art history: the writer, wearing a white cap, holds a plow in the sunlight, his beard flowing across his chest, the fertile black earth churning beneath his feet. Tolstoy later remarked that Repin portrayed the lives of the people better than any other Russian artist.

Ilya Repin, Leo Tolstoy Barefoot, 1901

In many of Repin's portraits of Tolstoy, a spiritual resonance transcends technical expression. Upon viewing Repin's masterpiece "Ivan the Terrible Killing His Son," Tolstoy exclaimed, "Repin is truly excellent! I cannot describe how this painting is so good! Such a superb technique, one can hardly discern the technique." Similarly, Repin confided in a letter to his critic Stasov, "My God, how all-encompassing is the soul of this Tolstoy! Everything that is living and breathing, the whole of nature, is reflected in him truly, without a trace of falsehood..." This spiritual resonance reached its peak in "Barefoot Leo Tolstoy," painted in 1901. On a two-meter-high canvas, Tolstoy, in a white shirt and black trousers, stands barefoot in the woods, his hands tucked into his belt, lost in thought. This painting has become an enduring symbol of this giant of simple thought.

Repin and Tolstoy's friendship reflects the magnificent interweaving of Russian art and literature in the 19th century. As Chernyshevsky posited, "Art is a reflection of reality" and "Art is a textbook of life," the two masters realized a shared ideal of realism through their respective mediums. Repin portrayed Tolstoy as both a literary genius and a down-to-earth farmer; a thinker who created immortal masterpieces in his study and a practitioner who toiled on the black soil. This duality reveals Repin's understanding of the intellectual: true spiritual nobility must be rooted in the national soil.

The founder of the "Republic of Art"

Repin's "circle of friends" extended far beyond Tolstoy. His artistic republic housed Russia's most brilliant composers, writers, and scientists of the time, inspiring one another and shaping the Golden Age of Russian culture in the 19th century. Throughout his life, Repin painted hundreds of portraits and thousands of drawings, many of which depicted his personal friends. Consequently, his epistolary legacy, comprising over ten thousand letters, bears witness to the depth and breadth of this illustrious circle of friends.

Ilya Repin, Portrait of Mussorgsky, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, 1881

Composer Mussorgsky held a special place in Repin's artistic circle. Upon viewing "Barge Haulers on the Volga," Mussorgsky wrote to Repin with emotion: "I see them even in my dreams, and even when I eat, I long to see them—the great, unglamorized, real life of the Russian people!" This profound observation of the grassroots became a spiritual bond between Repin and his fellow musicians. In response, Repin created a poignant portrait of the musical genius. Completed over four days at Mussorgsky's deathbed during his final moments, the portrait captures the composer's penetrating eyes and face swollen from alcoholism, becoming a treasure in both music and art history.

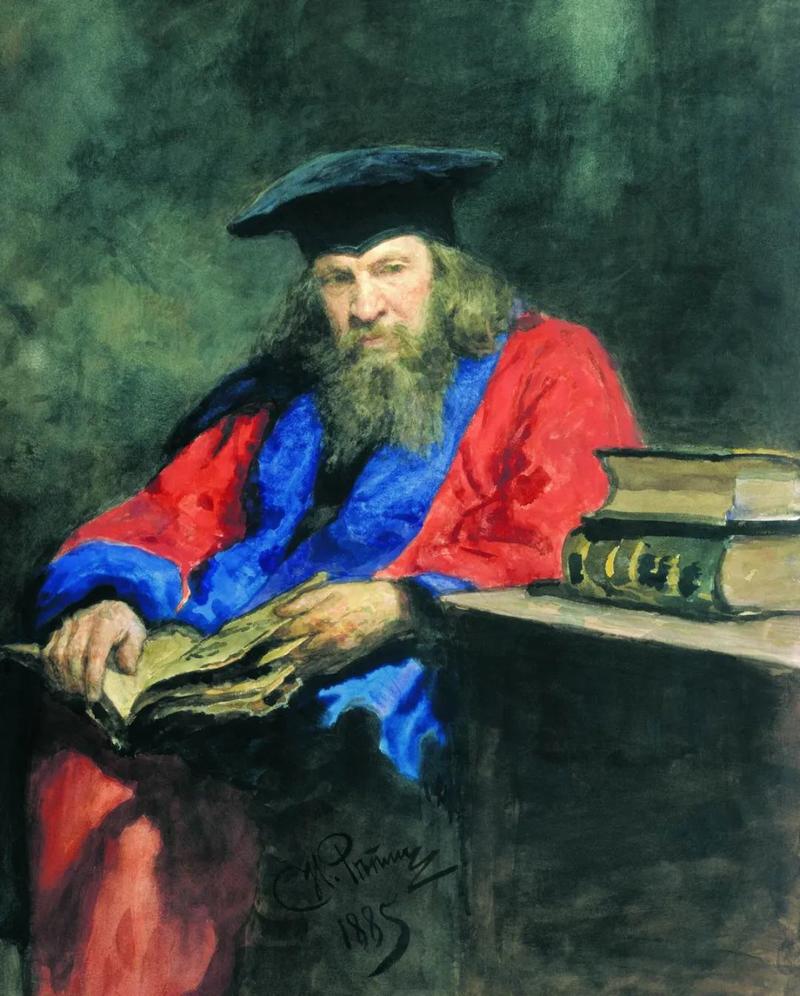

Ilya Repin, Portrait of Dimitri Mendeleev, 1885

Scientists also shine brightly in Repin's portrait gallery. He created portraits of the great chemist Mendeleev and the physiologist Pavlov, leaving behind a precious visual record of the Golden Age of Russian Science. These works transcend mere visual documentation and bear witness to the dialogue between science and art.

Ilya Repin, Ivan the Terrible Killing His Son, 1885, Collection of the Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Repin's literary circle is equally astonishing. He not only created numerous works for Tolstoy, but also painted portraits of writers such as Turgenev, Gorky, and Mayakovsky. Particularly noteworthy is Repin's portrait of the writer Garshin, which became the inspiration for the image of the prince in the famous painting "Ivan the Terrible Killing His Son." This cross-disciplinary fusion reflects Repin's unique creative approach: he never simply copied his models, but rather advocated that "copying the model is not enough for artistic creation; the painter must imbue his work with the enchanting charm and the impression that moved him."

Ilya Repin, Letter from the Zaporozhian to the Turkish Sultan, 1880-1891, Collection of the State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Repin's creative approach profoundly influenced the entire art world. Repin began conceiving "The Zaporozhian Reply to the Turkish Sultan" in 1878 and completed it in 1891. During this time, he created hundreds of sketches and drawings, revising the positions and poses of the characters dozens of times. As he fondly confessed, "I love the Zaporozhian people because they are courageous, skilled in defending their freedom and protecting the oppressed." This admiration for the spirit of freedom became the ideological cornerstone that connected Repin with his progressive intellectual contemporaries.

The Spark of Paintbrush Inheritance

As a central figure in 19th-century Russian art education, Repin's circle of friends encompassed not only masters of his own caliber but also the next generation of artists. His teaching at the Academy of Fine Arts made him a crucial link between two generations of artists, and his open and inclusive teaching philosophy fostered diverse artistic exploration.

Nikolay Feshin, Cabbage Harvest Season, oil on canvas, 219×344cm, 1909

Repin's educational philosophy was rooted in respect for individuality. Though a master of realism, he never restricted his students' stylistic exploration. This openness was best exemplified by Nikolay Feshin, a distinguished student at the Repin Academy of Fine Arts who, despite studying under Repin, developed his own distinctive, decorative style. Feshin's graduation work, "Cabbage Harvest Season," won the academy's highest award, earning him study tours to France and Italy; his "Unknown Woman" even received a gold medal at the Munich International Exhibition. Particularly noteworthy are Feshin's innovations in drawing: his use of a combination of line and surface to manipulate light and shadow remains a prime example for teaching in Chinese universities today.

Ilya Repin, The Council of State, 1901–1903

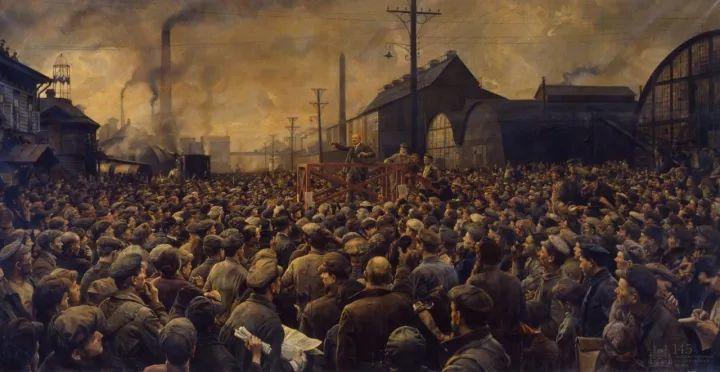

Another important disciple of Repin, I.I. Brodsky, chose a different artistic path. He inherited his teacher's profound concern for real society and became a prominent representative of Soviet Realist painting. When Repin created the large-scale oil painting "Council of State" from 1901 to 1903, Brodsky participated in this ambitious project. Repin had already sketched nearly 80 officials, including Tsar Nicholas II. Brodsky learned from his teacher's tradition of "the most detailed understanding of characters and the most realistic portrayal of social phenomena," an experience that profoundly influenced his later work. Brodsky later became the first Soviet artist to be awarded the Order of Lenin. His work, "Lenin's Speech to the Workers' Congress of the Pukkirov Factory, May 1917," continues Repin's spirit of realism.

I.I. Brodsky, Lenin's Speech at a Workers' Congress at the Pukkirov Factory, May 1917, 1929, 303 cm x 575 cm

Repin's educational legacy has been passed down through generations of his disciples, forming a profound lineage of influence. His student, Grabari, became director of the Moscow State Tretyakov Gallery and president of the Surikov State Academy of Fine Arts, and was the first professor to incorporate plein air drawing into the academy's curriculum. Grabari's student, Melnikov, later became president of the Repin Academy of Fine Arts, where he taught for over fifty years and trained numerous artists, including Chinese students like Li Tianxiang, Su Gaoli, and Wang Tieniu. This line of mentorship demonstrates the enduring vitality of Repin's educational philosophy—he was both a rigorous trainer of technique and a liberator of artistic individuality.

In 1930, at the age of 86, Repin passed away peacefully at his estate in Penat on the Gulf of Finland, bidding farewell to the great era he had captured with his brush. Reflecting on his interactions with Tolstoy, Mussorgsky, and numerous other cultural elites, we witness not only a personal friendship but also a collective biography of 19th-century Russian spiritual life. The more than 70 works Repin created for Tolstoy serve as a visual link, connecting the most brilliant intellectual constellations of that era.

Ilya Repin, "Religious Procession in Kursk Province" from the Tretyakov Gallery

Ilya Repin, Portrait of the Artist's Daughter, Tretyakov Gallery

Ilya Repin, The Unexpected Return, Tretyakov Gallery

When today's audiences see the sun-gilded faces in "A Religious Procession in Kursk Province" at the National Museum's special exhibition, feel the warmth and healing power of Repin's daughter's smile in "Under the Sun," or read the profound meaning of the revolutionary's serene face in "The Unexpected Return," the master artist's "circle of friends" transcends time and space, extending an invitation to every viewer. Tolstoy, as portrayed by Repin, still gazes at the world with a piercing gaze, as if reminding us: true artistic creation is always born from a sincere dialogue between hearts.