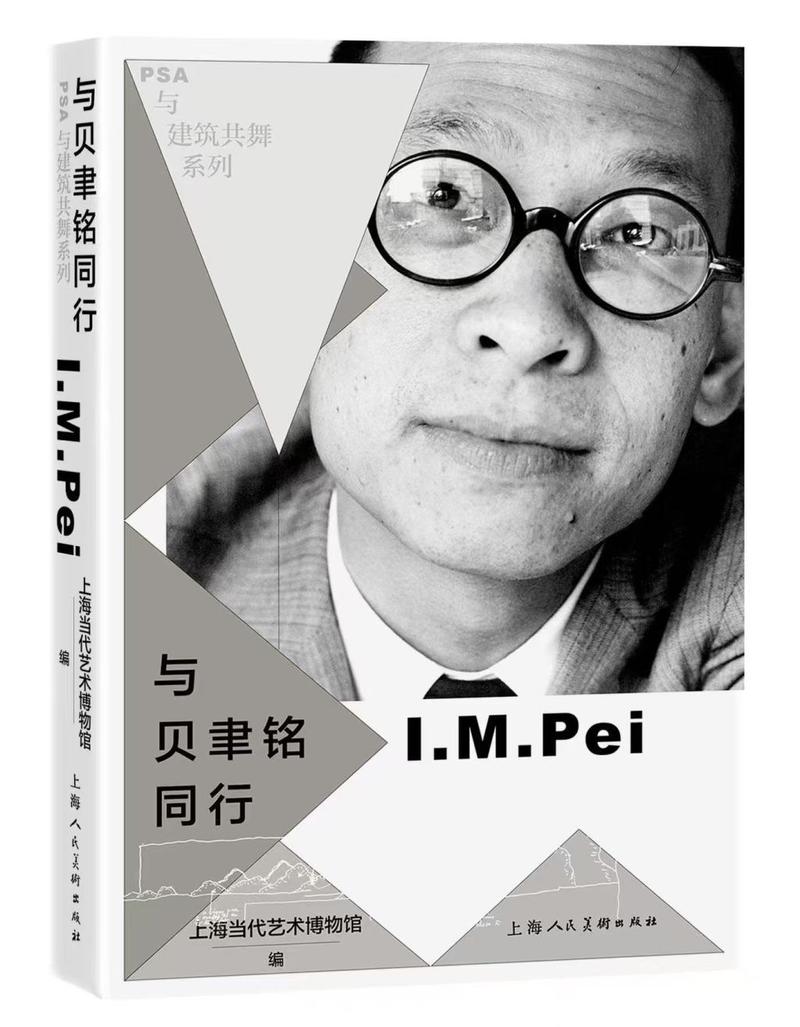

The Power Station of Art (PSA) Shanghai exhibition "I.M. Pei: Life as Architecture" closes on August 10. As a further extension and complement to the exhibition, the recently published book "Walking with I.M. Pei" brings together ten Chinese architects and artists, including Li Hu, Tang Keyang, Liu Yichun, Zhang Yonghe, and Xu Bing, who shared close ties with or were deeply influenced by the architect. These authors offer first-person perspectives on Pei's life and his inner world.

"The Paper·Art Review" has been authorized to publish an article titled "Variations of Geometry" written by architect Liu Yichun. In Liu Yichun's view, in terms of form, I.M. Pei's architecture has realized a design paradigm of "geometry is structure, structure is space", transforming geometric language into an architectural expression that can transcend time and culture.

I.M. Pei walking up the stairs of the East Building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. © Marc Riboud: Fonds Marc Riboud at MNAAG: Magnum Photos

Geometry is one of humanity's earliest forms of knowledge, originating from our intuitive perception of natural order and evolving into a rational tool. Natural phenomena contain geometric archetypes. Humans observed and memorized these forms, transforming them into practices like knotting, totems, weaving, and surveying, gradually forming primitive diagrams of shape, proportion, and space. These primitive diagrams evolved into culturally distinctive geometric representations across civilizations, such as the pyramids of ancient Egypt, the mandala of India, the Bagua diagram of China, the repetitive patterns of Islam, and the proportional mathematics of ancient Greece. The evolution of each geometric form is both a matter of perception and order and a concrete reflection of how different cultures perceive the world. The use of geometry in architecture can create a sense of sacredness and monumentality, as well as a spatial expression of order, logic, and political structure. Architecture, in turn, often manifests itself as a geometric form. As humans project themselves into architectural metaphors, geometry, in various forms, has entered into architectural representations and underlying proportional relationships.

In his book Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism, Rudolf Wittkower analyzes the works of Renaissance architects like Palladio to illustrate how geometric proportions carry the triple logic of rationality, the sacred, and style. In The Projective Cast: Architecture and Its Three Geometries, Robin Evans distinguishes between three architectural geometries: Euclidean, projective, and topological. He argues that geometry not only shapes spatial structure but also influences perceptual logic, serving as a mediating structure for the construction of style. In their book "Architectural Representation and the Perspective Hinge," Alberto Pérez-Gómez and Louise Pelletier analyze the axonometric arrangements in Le Corbusier's collection of poems and drawings, "Le Poème de l'angle droit," arguing that Le Corbusier was constructing a dialogue between poetry and geometry, between perception and order. By revealing the spirituality of orthogonal geometry, he emphasizes the relationship between the order symbolized by right angles and human existence. Le Corbusier once sought to justify the introduction of the modular system into architecture. Gómez argues that this can be understood as a poetic attempt to translate cosmic order into architectural language. Le Corbusier's modular system sought to preserve a comprehensible perceptual continuity for modern architecture as it parted ways with classical architecture. This, in turn, is a form of architectural rhetoric generated through the application of geometry.

The razor-sharp corners of the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, East Building, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (1968–1978), 2022. Photograph commissioned by M+, 2022. © Naho Kubota

I.M. Pei's architectural works are also imbued with a clear geometric language, and his firm consistently employs modular control as a design method. Whether this approach was influenced or inspired by Le Corbusier is unknown. However, what is certain is that Pei's geometry was not always derived from a priori diagrams, but rather from specific site relationships. This is particularly evident in his design for the East Building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. The East Building's plan is derived from a geometric fractal, generated by an understanding of the relationship between the site's shape, the surrounding roads, and adjacent buildings. Faced with an irregular trapezoidal site, Pei employed triangular fractals to find symmetry while simultaneously negating excessive symmetry. The geometry in the East Building's design is primarily planar but also structural. The structure here refers to a compositional structure that implicitly aligns with the axis of the West Building of the National Gallery of Art. The site borders Pennsylvania Avenue to the north, which runs southeast toward Capitol Hill. This creates an angle with the West Building's east-west axis, exerting an invisible pressure on the building's form within the site. I.M. Pei alleviated this pressure by shifting the East Building's central triangular skylight southward. In other words, while the East Building's facade facing the West Building is axially aligned, the axis of the atrium of the triangular skylight at the center of the East Building's plan does not align with the main axis of the building's facade. This is a key structural characteristic of the East Building. It is precisely this asymmetry within symmetry that gives Pei's architecture, while grounded in classical design, a unique ingenuity and vividness. This asymmetry within symmetry can be seen throughout his facade treatments. Of course, Pei's architectural work, with its extreme flatness and precision of surface and its commitment to geometric volume, exhibits an abstraction distinct from classical architecture, thus embodying a unique artistic modernity. So, in this sense, while the East Building's volume can be seen as a direct vertical transformation of planar geometry, thus highlighting its unique geometric form, we still believe that the geometry of the East Building is not a formal one, but a structural one.

The National Gallery of Art's East Building, Washington, D.C., USA, completed in 1978. Photo: Everyday Artistry Photography / Alamy Stock Photo, 2018

Looking across all of I.M. Pei's architectural works, a distinct shift in geometric language is evident: his geometry has gradually shifted from structuralism in early planar compositions to structuralism in concrete construction. This is particularly evident in the increasing number of Oriental buildings he built in China and Japan starting in the 1980s. In 1991, Pei designed the Miho Museum in Shiga Prefecture, Japan. He skillfully combined the Oriental sloping roof form with a hip roof design and his signature fractal geometry based on triangles, achieving a rod-based structure more closely aligned with Eastern construction traditions. This markedly differs from the solid structures more closely associated with "stereotomic" stonework employed in his previous architectural designs.

Miho Museum, Shigaraki, Shiga Prefecture, Japan, built in 1997. Photo: Iain Masterton / Alamy Stock Photo, 2007

The unique rod-based structural system used in the Miho Museum's sloping roof clearly harks back to the skylight structure of the East Building of the National Gallery of Art in the United States. A 1969 rendering of the East Building's atrium shows a ceiling constructed using a concrete grid. A March 1971 rendering of the East Building's atrium reveals that the original ceiling had been replaced with a transparent glass skylight with a spatial grid structure. This idea came to I.M. Pei nine months into construction of the East Building. It was this spatial grid skylight that distinguished Pei's triangular ceiling from that of Louis Kahn's new Yale Art Gallery and spawned the rod-based structure based on triangular geometry that would later flourish in Pei's Eastern architectural projects. The East Building's skylight structure and its sunshade system would be used repeatedly in many of Pei's later projects, including the Fragrant Hill Hotel in Beijing. But at the Meiho Museum, this rod-based structural system is an evolutionary design that is clearly intended to connect with local culture; it was also used in the design of the Suzhou Museum in 2000.

The Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong, designed beginning in 1982, and the glass pyramid in the Louvre renovation project in Paris, which began in 1983, are both variations on the triangular geometry-based spatial grid structure developed after the East Building of the National Gallery of Art in the United States. The Louvre's glass pyramid's conical surface utilizes a plane grid structure based on triangular fractal geometry, combined with a cable-net system derived from force-bending moment diagrams, to form a lightweight and efficient spatial grid structure. This structure reduces the size of supporting members by introducing cables, achieving a high degree of transparency and simplicity. The Bank of China Tower's design builds on the quadrilateral by incorporating triangles into the plane and volume, achieving a highly integrated geometry and structural loads. This supertall building, over 300 meters tall, eschews the traditional core to resist horizontal loads. Instead, it achieves structural stability through a diagonal bracing system composed of rods. This approach is a groundbreaking structural design move and also allows for flexible layout of standard floor plans. Although I.M. Pei likened the exterior of the Bank of China Tower to a bamboo growing segment by segment, in reality, it is perhaps the cleverness between structure and geometry that gives the building its inherent oriental charm.

The Louvre's shopping mall, Paris, France, completed in 1993, has an inverted pyramid-shaped top structure. Photo: Hercules Milas / Alamy Stock Photo, 2016

In 1999, I.M. Pei designed the Oare Pavilion, a small building in Wiltshire, England, which was completed in 2003. The pavilion's ground floor plan is a cross, but the raised floor and roof transform into an octagonal form that hints at both a cross and a triangle. The roof is supported by a steel truss structure combining quadrilateral and triangular elements, creating an almost ambiguous double eaves. The Oare Pavilion's structure was designed by Leslie Robertson, the structural engineer who previously worked on the Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong. Later, pavilions of this structure appeared in the Suzhou Museum and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, both of which Pei designed during the same period, demonstrating his continued interest in this structural configuration. The Oare Pavilion's architectural language blends classical geometric order with modern structural systems, while also featuring a highly abstract spatial expression, forming a geometric model that transcends scale, function, and geographic constraints. Perhaps precisely because of its cross-cultural potential, Pei repeatedly employed this form in his later architectural works in various countries.

Museum of Islamic Art (2000–2008), Doha, 2022. Photograph commissioned by M+, 2022. © Mohamed Somji

Suzhou Museum (2000–2006), Suzhou, 2021. Photographed on commission from M+, 2021. © Tian Fangfang

Whether it's Pei's early geometric structures based on planar composition or his later spatial geometric structures, derived from spatial truss systems and emphasizing the stable force-transmitting logic of triangles, both embody the dual qualities of geometric rationality and rhetorical tension. This geometrically grounded structural language creates a clear sense of rhythm and balance in space, imbuing architecture with a perceptible order. It not only embodies the rationality inherent in a professional stance but also offers sensual comprehension for audiences of diverse cultural backgrounds. This is a geometric form that can be physically perceived, structurally integrated, and culturally internalized. It is in this sense that Pei achieved a design paradigm of "geometry as structure, structure as space," transforming geometric language into an architectural expression that transcends time and culture.

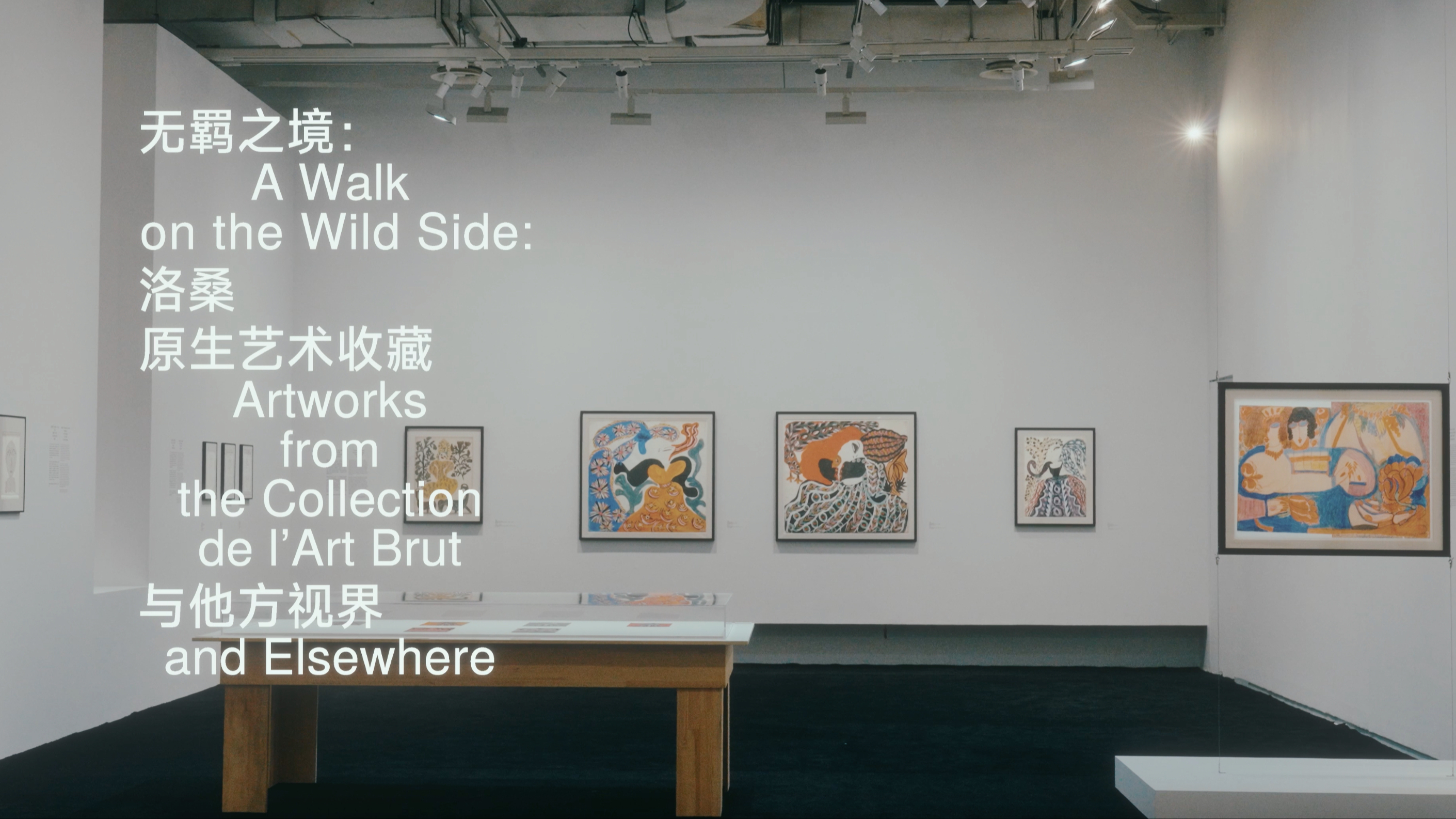

Exhibition view of "I.M. Pei: Life as Architecture" at the Power Station of Art, Shanghai

Book cover of Walking with I.M. Pei

(This article was originally titled "I.M. Pei's Geometric Variations")