Dai Shihe, a well-known oil painter in his 80s, was once the director of the Oil Painting Department of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, the dean of the School of Plastic Arts, and the president of the Chinese Mural Society. He is also one of the main practitioners of oil painting sketching and freehand oil painting in recent years.

The "Dog Days of Summer - Dai Shihe Oil Painting and Document Exhibition" sponsored by the Central Academy of Fine Arts and the Liu Haisu Art Museum was recently exhibited to the public at the Liu Haisu Art Museum in Shanghai. "The Paper|Art Review" conducted an exclusive interview with Dai Shihe.

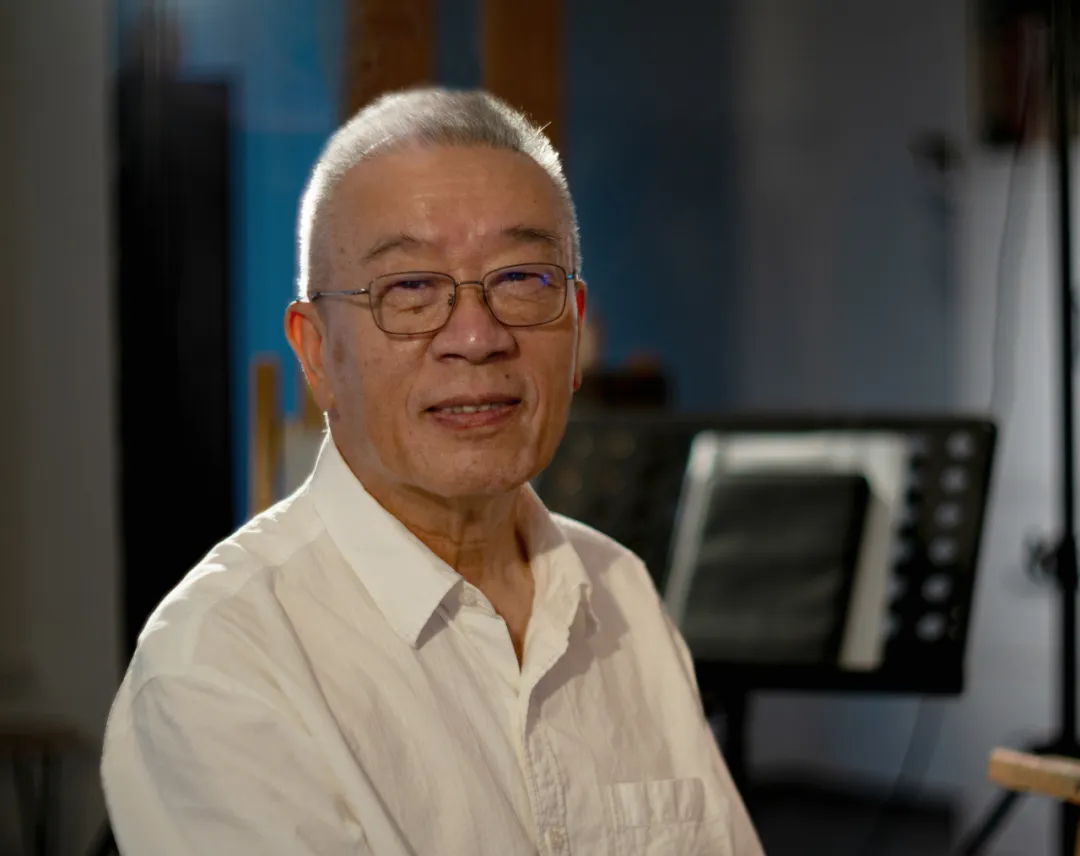

Born in 1948, Dai Shihe, with his short, pure white hair, looks younger than his actual age. He speaks with a thick Beijing accent, wears glasses, and is elegant and refined. Although he is an oil painter, as some commentators have said, "He is actually more like a literati in the oil painting world."

Oil painter Dai Shihe

The exhibition in Shanghai brings together 130 works in various formats, including oil paintings, murals, and sketches, along with documents. The exhibits span a wide range of time periods, starting with a 1958 sketch and a 1962 watercolor sketch of "Fragrant Hills." Oil paintings on display include "Young Xu Beihong," "Beneath the Studio Window," "Mother and Child," and "A Stack of Sketchbooks." Among them, paintings such as "Dog Days," "High Five with Me," and "Manlun Village" are being exhibited for the first time. Related sketches are also included in the exhibition.

A close reading of his works reveals his fascination with sketching, as well as his enjoyment of a studio-style life and reflection, particularly his admiration and research of Qi Baishi, Huang Binhong, Guan Liang, and Lin Fengmian. In fact, he studied at the Repin Academy of Fine Arts in his early years. However, during his travels throughout Europe and his artistic practice, he deeply felt the importance of national spirit in oil painting, and sought to incorporate the "freehand spirit" of Chinese art into his paintings. "No matter how good or how much I enjoy Western oil paintings, they are only nourishing. The classics of Chinese art, no matter when you begin studying them, are part of your blood," he told The Paper. "Freehand painting refers to both a painting technique and a spirit."

Mother and Child, oil on canvas, 30.5x30.5cm, 1985

To truly explore the roots of the concept of "freehand oil painting," beyond his teacher, Mr. Luo Gongliu, we might also need to trace back to Dai Shihe's childhood and the influence of his family. As Zhang Xiaoling, the exhibition's academic director, put it, "The first nurture of his art was a profound sense of simplicity, emptiness, and a refined, profound aesthetic, emphasizing materiality. This, to some extent, confirms a belief I've held for many years: that both humanity and art are products of childhood memories."

The Paper : Let’s start with the name of your exhibition, “Dog Days of Summer.” The last work in the exhibition is a small painting of a watermelon. Now that the beginning of autumn has passed, is this also your first comprehensive retrospective exhibition in Shanghai?

Dai Shihe: I've held exhibitions in Shanghai before, but this is the first time I've had such a comprehensive exhibition, complete with so much documentation. The exhibition's final small oil painting, "Dog Days," depicts a watermelon. While the subject matter and the canvas are both small, within this tiny space, I embody my pursuits in oil painting, life, and my career. The exhibition's title, "Dog Days," is both fitting and fitting, as the heat is intense and demanding. There's a saying, "Train in the dog days of summer, and the coldest days of winter," and artists all endure this. On the other hand, the dog days are actually the end of the dog days; it's already the beginning of autumn, and harvest season is quickly approaching.

Dog Days, oil on wood panel, 35x35cm, 1997

The Paper: Let’s start with your family in the documents on display, starting from your school days, including the influence of your family, the Children’s Palace, the factory, and then to the Central Academy of Fine Arts. Do you think this experience had a profound impact on your later theory and creative practice of freehand oil painting?

Dai Shihe: Yes, the teachers and elders who were close to me created excellent learning conditions for me from a young age. If I were to say family influence, it was actually the influence of the overall cultural atmosphere. My father was a very good painter, a quick sketcher. He loved painting and had studied it. He studied at the Peking Academy of Fine Arts, where Zhang Henshui was president. When I was young, my father took me to exhibitions. From a very young age, he took me to various national art exhibitions and oil painting exhibitions. I saw a lot of them, and listening to his various opinions had a great influence on me. But he never pressured me to learn, telling me to paint this way or that way. Never, not even once.

The Paper: From the very beginning, you are given an environment where you can freely face art.

Dai Shihe: Yes, as a child, I was studious, but I was also spoiled by my family. We had particularly good art albums, and I'd tear out the contents. I remember one was a collection of Käthe Kollwitz's paintings edited by Lu Xun. (Thinking back on it now), it's quite precious. My father never criticized me; he thought sketching was a good thing. My family never forced me to learn to paint; they just let me enjoy it. My father had a real influence on me. Back then, he took me for a walk and told me, "In winter, the leaves have all fallen, but not a single branch is not beautiful." I still remember this sentence today. He didn't say, "Look, this is beautiful," but "Not a single branch is not beautiful." It's all life. I've always remembered this. It was truly the influence of the family atmosphere, not the specific, "I have to teach you, you want to sketch, but the colors aren't right, you have to start with sketching." My formal art education began at the Jingshan Children's Palace in Beijing. Back then, admission was based on academic performance. The art education there had a very formal impact on me. The painting "Fragrant Hill" I created in junior high school was from that time.

Dai Shihe and his brother drew Dai Shihe reading in 1957 (left), and a sketch of 10-year-old Dai Shihe in 1958

Dai Shihe's portrait of his father at the age of 100

The Paper: Is the art education received at the Children’s Palace different from the free-range education at home?

Dai Shihe: It was different. Every child at that time was very proud and felt that they were little adults. They felt that their paintings were not children's paintings, and they felt ashamed to paint children's paintings. At that time, everyone had a very high opinion of themselves. There were only so many adults in the whole of Beijing, and very few people could enter the Children's Palace to study art. At that time, it was considered formal education, and no one felt that formal education conflicted with my personality. No, I felt that it was a way to improve, enrich and nourish my personality, so everyone was willing to learn.

The Paper: Did the Children’s Palace have different types of paintings at that time?

Dai Shihe: There are two types of painting: oil painting and traditional Chinese painting. Wang Mingming and his classmates studied traditional Chinese painting, while I was in the oil painting group. After the Children's Palace, it was 1966, and many of my classmates went to the countryside to work in the fields. I was lucky enough to stay in the factory and became a propaganda cadre. I was later admitted to Beijing Normal University and then the Central Academy of Fine Arts.

The Paper: This journey in artistic pursuits is truly fortunate. Nowadays, when people mention you, they often associate you with freehand oil painting. In fact, freehand oil painting isn't just practiced by this generation; it dates back to the Republican era. It can be said that Chinese oil painters have long been exploring nationalistic approaches, including the theories proposed by Mr. Luo Gongliu. You have deepened and systematically summarized his theories. Could you please share more about your journey?

Dai Shihe: The modern and contemporary concept of "freehand oil painting" and the idea that "oil painting should be freehand" was coined by Mr. Luo Gongliu, who had just returned from studying in the Soviet Union in 1959. He stood out among the painters who had studied there. He was absolutely unconventional and possessed his own unique perspectives, which was truly remarkable. Upon his return, he declared that we shouldn't blindly follow European oil paintings, arguing that many paintings in museums were still subpar. He summed it up in seven words: "Complexity, tediousness, and rigidity." He believed this was not the quality of an artist, and that China's thousands of years of tradition were no less artistic than theirs. "We should combine the Chinese freehand spirit with the powerful expressiveness of oil painting to contribute to the world." Mr. Luo proposed this idea, probably in the 1950s. What a vibrant atmosphere then! At the time, most paintings were copied from Soviet art. While he felt that the Soviet Union had many excellent works worth learning from, he also insisted that we shouldn't blindly follow the Soviet Union; we must exercise our own independent judgment. He personally strove to achieve this in his teaching and creations, but by 1966, he had put his work aside. Many years later, after I'd grown up, Mr. Pan Gongkai mentioned to me the importance of freehand brushwork in oil painting and asked me to write a textbook, hence the name "Freehand Oil Painting." In fact, modern European works also have their own freehand touches. Monet's large "Water Lilies" are so freehand, and even Rembrandt's late "The Return of the Prodigal Son" is quite freehand. I believe these works share a high-level connection, not opposition.

Exhibition site

The Paper: Freehand brushwork itself is a long-standing tradition in Chinese art.

Dai Shihe: Yes, it should be more refined, more flexible, more simple, and more direct, instead of doing it like a handicraft. I think this is true. My teachers, Mr. Luo Gongliu, and we have all explored this all the way since we started learning oil painting. Chinese people cannot forget the good things left by our tradition, and it is best to combine these.

The Paper: When did you write the Italian oil painting textbook?

Dai Shihe: 2007.

The Paper: I just saw paintings by several masters of Chinese freehand brushwork in the exhibition hall, such as Qi Baishi, Huang Binhong, Guan Liang, etc. Mr. Guan Liang, you have also said before that Qi Baishi and Huang Binhong have a great influence on your oil paintings. How do you understand this?

Dai Shihe: Regarding the influence of Chinese painting on oil painting, I really like what our predecessors said, "No matter how good Western oil paintings are or how much you like them, they are only nourishment. The classics of Chinese art, no matter when you start learning them, are your blood." This hits the nail on the head. Don't think that you are Soviet-style just because you have learned a little bit of foreign things, or a little bit of Russian things. In fact, there is a huge difference. Russians will never consider your paintings to be Soviet-style. The only way out is to inherit our own traditions well.

Dai Shihe, Lin Fengmian, oil on canvas, 180x60cm, 2022

Dai Shihe, "Young Xu Beihong", oil on canvas, 180x100cm, 2025

The Paper: You just mentioned nutrition and blood. When you went to the Repin Academy for further studies, did Repin and the famous artists of the Itinerant School have any influence on you?

Dai Shihe: Repin's paintings are fantastic, of course they are fantastic, but the problem is, I can't. Whoever can, can. I've never seen anyone truly paint like Repin. I admire Repin greatly, but my paintings are completely different from Repin's. That's the truth. I also particularly admire Surikov, Rembrandt, the Impressionists, and Van Gogh. I admire them immensely, and I would never dare put myself behind them. I can't paint like them, I really can't. We are just Chinese, playing chess and drinking tea, and that's how we get by.

Dai Shihe's Collected Works: Under the Studio Window

The Paper: You're influenced by many aspects of your family, including the lifestyle of a literati painter. Another point is that freehand oil painting, like Chinese freehand brushwork, requires a high level of cultural attainment.

Dai Shihe: You're absolutely right. Freehand brushwork is about the accumulation of concepts and cultural cultivation. Take Liu Haisu's lotus paintings, for example. You'll see a lot of freehand brushwork, expressing his emotions and temperament. This person must be a person of character, sincere, for the brushwork to express it. Just like what I just said about being "grabby and greasy," such a person can't have true freehand brushwork. That's not painting, it's crafting.

The Paper: Mr. Luo Gongliu mentioned the reduction and simplicity of freehand painting. I was deeply impressed by your works "Watermelon" and "Mother and Child". The brushwork is very simple, and a lot of your emotions are incorporated into them.

Dai Shihe: The word "simple" here actually means I am afraid of being "chatty" in the picture. I can say it clearly in one sentence, but I still want to show off. So I changed the way I put it. I try to be clear, simple and straightforward to make things clear. Don't be too rambling or show off, just don't be nagging.

The Paper : Simplifying the complex, here it seems like Liang Kai, Bada Shanren, Xu Wei, and Qi Baishi are all influenced by the same lineage. Just now in the exhibition hall, you said that the protagonist of one of your paintings is Qi Baishi. Can you tell us more about the influence of Qi Baishi on your creation?

Dai Shihe: I've never been against Qi Baishi since I was little. I can only say this because my parents watched so many foreign films when I was little, and I couldn't resist, always wanting to watch them. So, growing up in a Western culture, I enjoyed symphonies, ballet, drama, and foreign films, not Peking opera or Chinese painting. When I was little, I couldn't really listen to Peking opera. Only after a certain amount of experience did I come back to it and appreciate its beauty. Every word and every sentence was so well-deserved! Looking back at all of Qi Baishi's works, I'm drawn to their simplicity, purity, and freehand style more and more.

Dai Shihe, High Five with Me, oil on canvas, 170x190cm, 2024

The Paper: When did you start to become interested in Peking Opera?

Dai Shihe: Too late, after I turned 30. It was only after a period of ups and downs that I became interested in traditional art, including Peking Opera and Suzhou Pingtan, and I became deeply attached to it, much like my later love for Qi Baishi and Huang Binhong. What I admire most about Huang Binhong is that he was more than just a painter. He had a big heart. When he was young, he joined the Tongmenghui with his friends, distributing leaflets, risking his life. He had such a strong sense of patriotism. This wasn't just some ordinary, honest painting; he had a sense of social responsibility. Such a person is truly remarkable.

Dai Shihe's paintings of Huang Binhong (left) and Qi Baishi (right) at the exhibition

The Paper: Let’s get back to your specific creations. I see that there are many of your sketchbooks and quick sketchbooks in this exhibition. You call them diaries. In what ways do sketchbooks and diaries like these influence your creations?

Dai Shihe: Sketching from life is the essential path to learning painting. Learning to sketch is like learning to observe, listening to what nature has to say, and constantly being nourished by the natural beauty of mountains and rivers. Speaking of diaries and manuscripts, take Qi Baishi, for example. In fact, there are actually numerous drafts left by Qi Baishi, as many as his finished works, including sketches. Some of these drafts have notes like "This section should be two centimeters longer" beside them. These are his true creative journey, his thoughts and creativity. Speaking of Rodin, I remember visiting the Rodin Memorial Museum in Paris. What impressed me most was that he created so many works in his life, but we didn't know about them. We only knew about "The Burghers of Calais", "The Age of Bronze", "The Thinker" and a few other works in the past, but in his memorial museum, his works are simply overwhelming. His mind is always thinking and creating. As an artist, his thinking has never stopped. It has always been a surging and continuous creation. That is Rodin, just like Qi Baishi behind the manuscript is Qi Baishi. That is the most admirable thing about an artist, a strong creative state.

The Paper: When you were the director of the Oil Painting Department at CAFA, could you share with us some of your thoughts on teaching and Chinese art education?

Dai Shihe: I think our modern art education differs from that of our predecessors, like Shitao and Qi Baishi. It's now an integral part of university education, art education. How to integrate academic art education with mentorship and the artist's real-life creative experience is a major challenge, one that hasn't been fully addressed in the West. We're also embarking on this path. Few artists actually have apprentices in their studios these days, as it's become socialized and a component of university education. This has led to many problems. Teachers don't necessarily paint themselves, and art professors in Western universities aren't necessarily artists themselves. Universities, after all, have their own cultural system, so they arrange for mentors to interact and exchange ideas. Every school has its own artistic vision. We need to gradually develop a Chinese, contemporary form of artistic creation, and only then can we develop a teaching model that serves it. Achieving this level of artistic achievement will take time.

Exhibition site

The Paper: You mentioned the “seeing the brushstrokes” and “writing” of oil painting. Could you elaborate on that?

Dai Shihe: My personal hobby is, for example, not tracing when writing. It doesn’t matter if it’s crooked. I can continue it in the next step and integrate it in the next step. The advantage of having brushstrokes everywhere on the picture is that there is a kind of spiritual temperament. The author can take responsibility and is not artificial. He stands up and says that this is how I draw. This stroke is biased to the left, and the next stroke is biased to the right, and when they are put together, it is correct.

Oil paintings can also be "written," and their flavor can be "written." Compared to "tracing," "writing" captures not only the form but also its meaning. Each stroke of "writing" contains a greater intensity of spiritual activity. The benefit of "writing" lies not in introducing the routines of calligraphy but in opening up new vitality.

Exhibited Works

The Paper: What is the state of mind you most desire in painting?

Dai Shihe: Seeing some of my contemporaries paint so well, and seeing the paintings of many young people, I'm deeply impressed not only by their skill, but also by their realm, their broad vision, their wisdom, and their sincerity. As for myself, I'm increasingly turning painting into a direct expression of my own state of mind. I strive for sincerity and simplicity, directness rather than indirectness. Every stroke is like my electrocardiogram, a pure expression of my own heart. This is a characteristic of mine. On the other hand, I've always felt that the true realm of the masters is their understanding of the wisdom of life, something I can never reach. There's a huge gap, so I'm trying to get closer to that by reading, keeping a diary, and creating. I've only reached that point now. There's a Chinese saying, "When you see a virtuous person, you should aspire to emulate him." It's true.