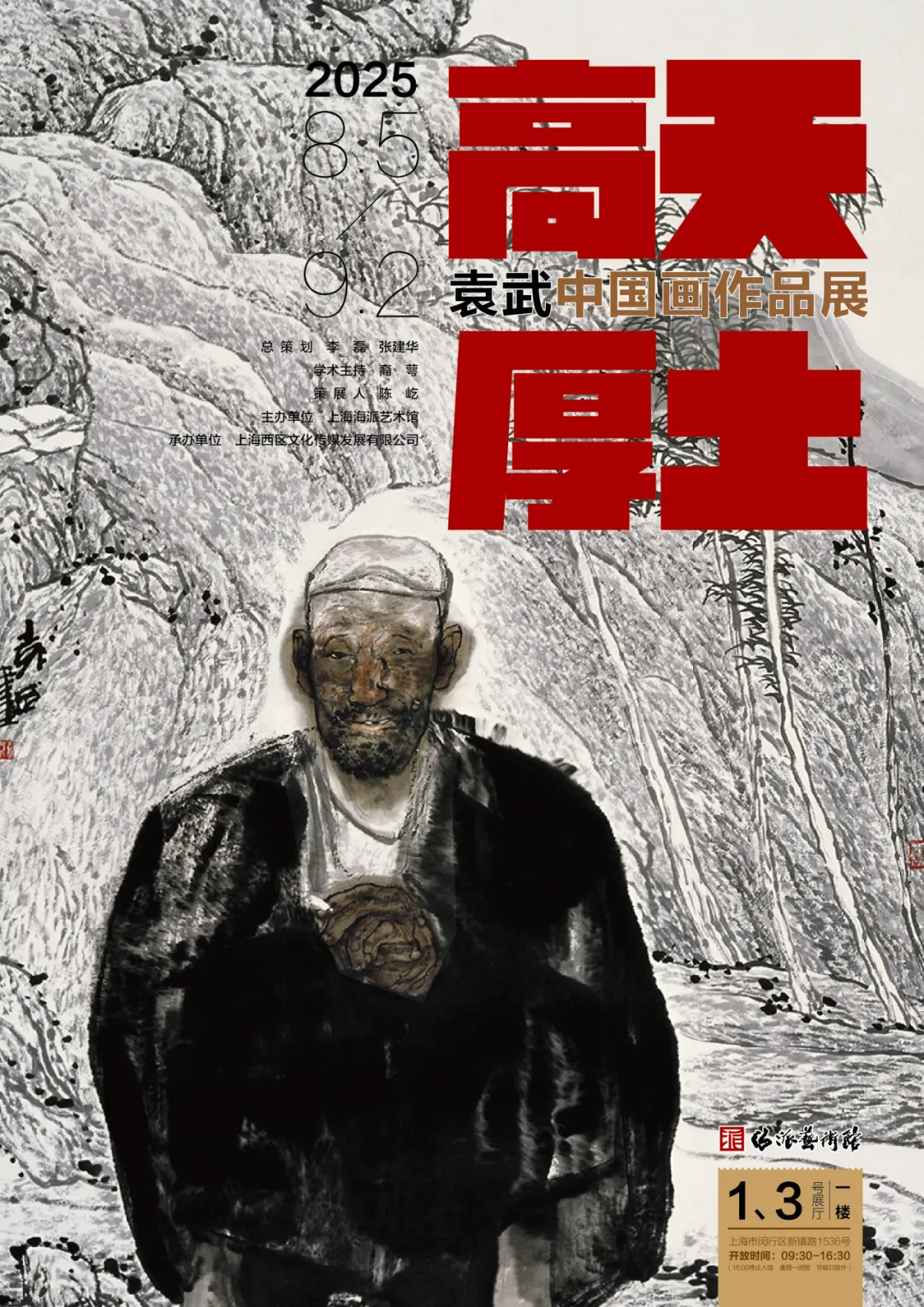

Born in 1959, the famous painter Yuan Wu was once the executive director of the Beijing Academy of Painting. He is unique in the field of Chinese figure painting with his heavy brushwork. By deeply cultivating the brushwork techniques of large-scale figures, especially the depiction of farmers and cattle, and Tibetan figures, he integrates the realistic tradition with the contemporary freehand spirit. His paintings have the simplicity and compassion between the vast sky and the fertile land. His paintings are like his personality. When you meet Yuan Wu himself, you will feel the same simplicity and honesty.

The "High Sky and Thick Earth - Yuan Wu Chinese Painting Exhibition" currently on display at the Shanghai Haipai Art Museum is Yuan Wu's first exhibition in Shanghai. In an interview with "The Paper|Art Review", Yuan Wu said that Shanghai's He Youzhi, Liu Danzhai, Fang Zengxian and others had a great influence on his figure paintings. Just as depicted in the exhibition "Farming on the Landscapes of Zhu Da (Bada Shanren)", he "has always been fond of the spirit of traditional painting" and pursues simplicity and sincerity in art, as well as a true realism.

Yuan Wu

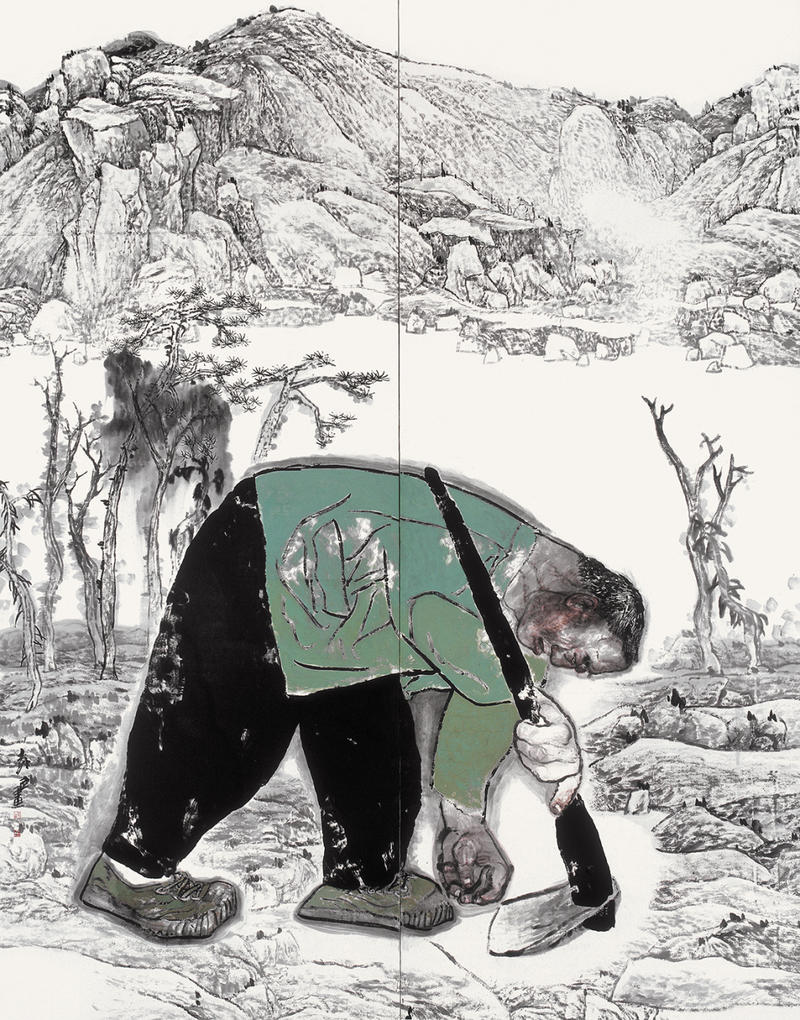

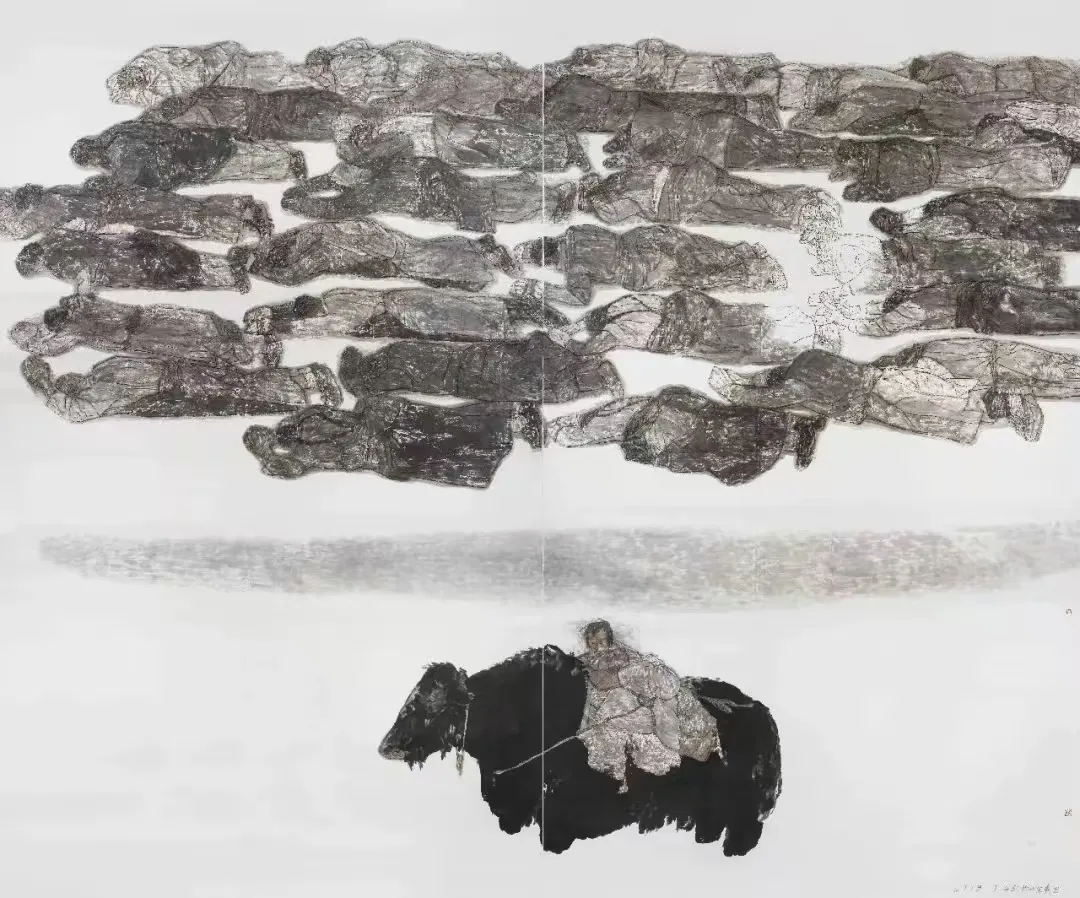

Farming on the Zhuda Mountain Water (366×290cm, created in 2011)

The Paper: This exhibition is also your first in Shanghai. You chose the two perspectives of high sky and thick earth, and most of your works are large-scale. Many people mentioned your realism. In fact, I think your understanding of realism is different from many people's understanding of realism nowadays.

Yuan Wu: I'd never held an exhibition in Shanghai before, and Shanghai art has been incredibly nourishing to me. Speaking of realism, I used to have a rather simplistic understanding, thinking it simply meant realistic expression. Later, I discovered there were critical realism and socialist realism, the latter characterized by its emphasis on eulogy. While this certainly has its merits and can be inspiring and positive, some works have become pseudo-realistic.

The Paper : There is a lack of sincerity.

Yuan Wu: Yes, because true realism touches the heart and embodies a critical and reflective spirit. True realism is scarce today, especially in major national exhibitions, where so many works are identical or similar, with overlapping themes and a rush to paint whatever they want. I actually believe painting is a deeply personal endeavor. I once said, "China has the most painters in the world, but it also has the fewest." Why? Because we have so many painters, but few of them truly reflect their lives, their feelings, or their deepest thoughts. They simply parrot superficially. For example, Jiang Zhaohe's "Refugees" and many other works painted before 1949 express personal feelings and experiences of life. Such works are rare today. I now realize that although I am a realist painter, I have two distinct orientations. Early on, I was socialist realist, while now I strive to be personal, down-to-earth, and reflective of everyday life, moving me and focusing on the human heart and destiny.

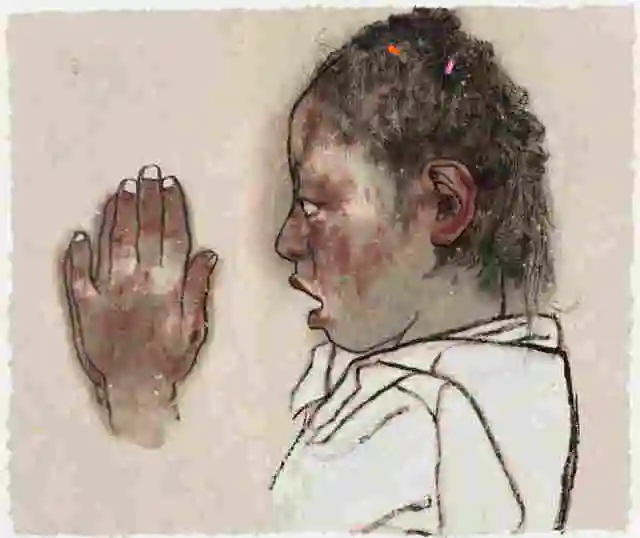

Details of Yuan Wu's paintings

The Paper: In fact, the farmers and cows in your paintings even reflect a sense of history, as well as a concern and reflection on the fate of ordinary Chinese people.

Yuan Wu: It should be said that the best painters are those who can paint their thoughts and ideas, but I can’t do that yet. I think I should be able to express my emotions and my mood now, but I can only do this, but I can be sincere and sentimental.

The Paper: A line in a Chinese painting carries the artist's emotions and accomplishments in brushwork. Your lines have a taste of astringency and metal and stone. What do you think of lines?

Yuan Wu: Chinese painting is essentially the art of line, with line modeling being a crucial form of expression. My habit is to use a slow brushstroke, which creates the metallic, stone-like quality and astringent quality you mentioned. Therefore, my paintings lack the strong rhythmic quality of a fast brushstroke. An artist's expressive methods can't all be strengths; if you emphasize one strength, you lose another. The use of lines and brushstrokes in a work may reveal an artist's emotions and accomplishments, but they don't necessarily convey the artist's character. A painter's character is revealed through a comprehensive examination of the work.

Some young artists today paint for the sole purpose of exhibiting, participating in official exhibitions, and aiming for success by getting selected or winning an award. This isn't the mindset of a true artist. I paint for myself now. I paint when I'm inspired, and after I'm done, I closely monitor the results of the painting, often revising it.

The Paper: I am reminded of Huang Binhong’s landscape paintings, where he would repeatedly dot and dye the landscape, looking at it and then adding more, and he would use very thick rice paper.

Yuan Wu : Yes, Huang Binhong is very inspiring to me. One year, the Zhejiang Museum held an exhibition to celebrate the 140th anniversary of Huang Binhong's birth. I went to see it and noticed that many of his paintings were actually sandwiched between glass and hung in the exhibition hall, allowing both sides to be viewed. I imagine that when Huang Binhong finished a painting, he couldn't decide which side was better, so he didn't write an inscription or frame it. This was his painting method and state of mind. He had his own standards and criteria, which are not what we usually understand. Why are so many artists today so mediocre? It's because they lack individual pursuit and independent heights in both subject matter and expression. They always adhere to a common, impersonal standard. In fact, artists must have their own standards and pursuits. Just as mathematics, physics, and chemistry can all be divided into right and wrong, art cannot be simply divided into right and wrong, or only into high and low artistic standards.

The Paper: Ouyang Xiu said, "Articles are like fine gold and jade, and they have their own prices in the market." Good articles and good art will be judged by time.

Yuan Wu: Yes, the standards can be different, but there must be a distinction between high and low.

Yuan Wu's paintings

The Paper: So we see many works of art that may be popular for a while, but become short-lived after ten or twenty years and disappear like duckweed.

Yuan Wu: Yes, but there are also many works that stand forever like mountains, like Fan Kuan's "Traveling in Mountains and Streams." Art is not science, and it can be said that the art of painting is not progressing. Just because Fan Kuan existed in the Five Dynasties, does that mean that Shen Zhou of the Ming Dynasty surpassed him? Or that Shi Tao of the Qing Dynasty surpassed Shen Zhou? Or that Huang Binhong surpassed Shi Tao? No, every era has its mountains, and mountains echo each other from afar, forming peaks of art.

The Paper: They gazed upon each other, inspired each other, and reflected each other. We just talked about Huang Binhong and Fan Kuan. Looking back at your upbringing, we all know you were deeply influenced by the "Xu-Jiang system" established by Xu Beihong and Jiang Zhaohe. I noticed that in the preface to your exhibition at the Shanghai School of Art, you said, "I have always admired the spirit of traditional painting."

Yuan Wu: When I first started learning Chinese painting, I definitely began within the context and spirit of Chinese painting, using the traditional Chinese copying method. When I entered university, my art education wasn't actually Chinese. The traditional Chinese painting apprenticeship system was master-apprentice, but at university, I was taught Western painting. This broadened my scope and supplemented the scientific modeling training of Western painting. My understanding is that without the fundamental skills of sketching, it's impossible to create a good modern figure painting.

The Paper: But among the famous artists of all ages, there are so many who are good at figure painting, such as Liang Kai’s figure paintings.

Yuan Wu: Yes, his artistry was exceptionally high, but that was a period in traditional Chinese figure painting, a peak, arguably. However, modern Chinese figure painting is now a must. Splashed ink alone isn't enough to express reality. We can't reach the artistic heights of Liang Kai, but with Liang Kai and his splashed ink series, there's no need for us to repeat ourselves. For example, I now try to minimize the variations in line and ink in my work, emphasizing the pure expression of line and ink while increasing the intensity of form. Yesterday, I was talking with Professor Zhang Peicheng. I remarked on his excellent painting skills, noting how relaxed and free his images are, something I can't achieve. My biggest frustration now is that I'm too tight in my drawings, too precise in my portrayal of form, and not relaxed enough. So I told Professor Zhang Peicheng, "My biggest frustration is my inability to feel free." I said, "Admit it or not, the looser the painting, the better." He said, "Of course, that's universally acknowledged." But looseness doesn't mean sloppy painting. I want to be free, but I just can't. It's true that Liang Kai's paintings are very loose and free, but that was the art of that era.

The Paper: Song represents freedom and ease, and is related to one’s mind. Perhaps you have a strong sense of realistic mission in your heart, and you may be greatly influenced by the Xu-Jiang system and Repin.

Yuan Wu: Our generation was definitely influenced by the foods we ate growing up, and that's undeniable. This includes storytelling and social concepts. After I turned fifty, I began to neglect storytelling in my work, avoiding it as much as possible. However, as my artistic practice matured, storytelling and a sense of mission became key elements. Actually, how much of a role does a painter's sense of mission really play? This is something I only realized later. But my approach to painting remains very serious. I strive to create works that resonate with everyone, and that's all I need. A painting's style reflects one's personality. If you're both clumsy and serious, your paintings will likely reflect that as well. You can't create something humorous, lighthearted, or elegant and lyrical—it's impossible.

The Paper: But the eyes of the cows and the old man in your paintings seem to go straight to the heart, simple and vivid.

Yuan Wu: Also, because I'm from Northeast China, my experience is somewhat unique. After graduating from high school, I spent three years as an educated youth in the countryside. After returning to the city, I worked as a worker for two years before going to university. Later, I taught at a middle school and a technical secondary school, and then pursued graduate studies. After that, I served in the army for 14 years, both as a soldier and a university teacher. At 50, I retired to work at the Beijing Academy of Painting, having experienced both work as a worker, a peasant, and a soldier. I was first Vice President, then Executive Vice President, then Legal Representative, and Executive President. Regardless of my position at the Beijing Academy, painting remained a constant focus. When I was a leader at the academy, I had two offices: one for my studio and the other for administrative matters. However, I almost always worked in the studio, calling everyone to come, painting while I handled my duties. I considered painting to be my most important priority.

The Paper: Actually, after going around in circles, the core is still around creation and expressing yourself through creation.

Yuan Wu: Yes, express yourself.

The Paper: And it feels like this state is very strong.

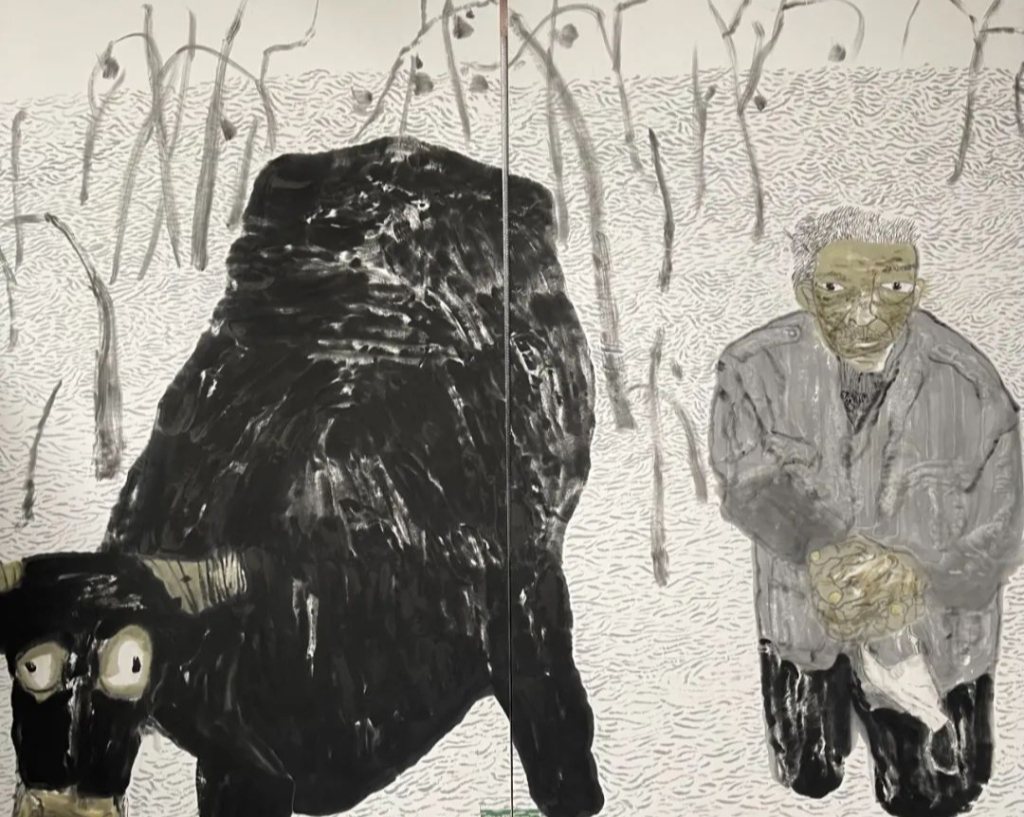

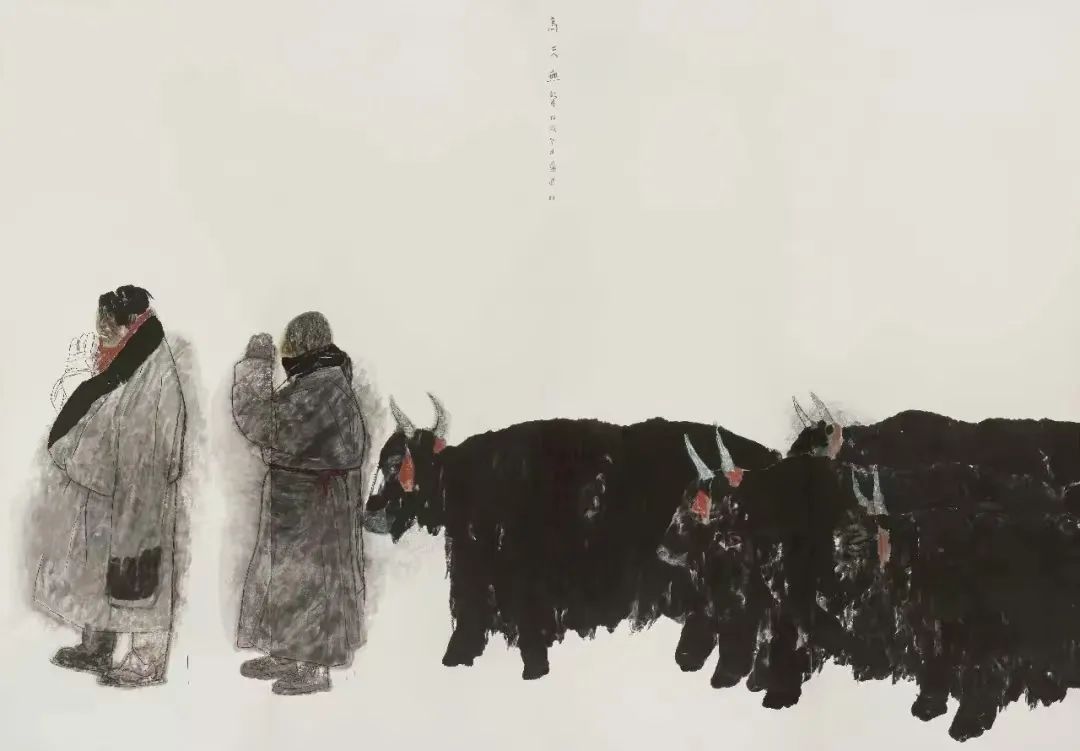

The Silent Sky, 2018

Yuan Wu: At this exchange meeting in Shanghai, everyone praised my energy, hard work, and dedication. I absolutely don't view painting as a job I must strive for or struggle with. Honestly, it's a hobby I deeply enjoy. I can't turn something I love into a chore. If I don't paint, nothing feels fun. Every morning, I drive to my studio, face a large sheet of rice paper, and conceive my paintings. In recent years, I've been painting large 2x2 meter portraits. Because of the subject matter, this series can neither be sold nor exhibited, but I desperately want to paint.

The Paper : Indeed, passion is the most important thing. By the way, you served as executive director of the Beijing Academy of Painting, but later resigned. What was the main reason at the time?

Yuan Wu: I'm not good at administrative work, and even worse at being in charge. When I was Vice President and Executive Vice President, I just did my job. But then I became Executive President and legal representative. I had to sign off on all the infrastructure costs for the organization. We were building a complex at the time, and there was so much money I couldn't even count, but I had to sign, which was very stressful. In my life, regardless of fame or fortune, I always avoid areas I'm not good at and strive to do what I'm good at. Quietly painting is what I want to do most.

The Paper: Any true artist would probably do this. When I heard you talk about the choices in life just now, I thought that your choices in painting are also very interesting. Style is the person, and the quality of the painting is the quality of the person. The choices you make in life and the choices you make in painting are also connected.

Yuan Wu's paintings

Yuan Wu: I should say so. It might not be absolute, but it at least accounts for the majority of the painting. A good painter's paintings will definitely make choices and not try to cover everything. So, when measuring the quality of a painter's paintings, the stronger the overall sense, the higher the artist's level. If they try to cover everything, the lower the level, the more vulgar and fragmented, and definitely not a good painting. I dare say this is a very important criterion.

The Paper: Indeed, vulgarity and fragmentation are actually related to subjectivity. Without choices, there is no self.

Yuan Wu: As I just summarized, I have my own internal criteria for painting, which others might also share. For example, I focus on capturing the essence up close and the momentum from a distance. When I paint a cow, I always devote the most ink and effort to the eyes and lips. I find the texture of those areas particularly appealing, especially the cow's eyes. When I look into their eyes, I empathize. I feel that only the eyes of a cow, a dog, and a human can communicate with each other. Looking at each other, yet unable to express themselves, creates a profound sense of sadness. Therefore, I particularly enjoy painting the eyes. As for other areas, such as the back, belly, legs, and knees, I rarely dwell on them. As long as the cow's volume is captured and the feeling is right, that's all that matters.

Old Man and Ox, 145×145cm, 2011

The Paper: That’s true. You have to make choices. And it seems that you have always had a sense of mission in the creation of modern figure paintings?

Yuan Wu: I hope that the best painters of our time will work together to create truly modern Chinese figure painting. "Chinese learning as the essence, Western learning for practical application" was coined by Zhang Zhidong. A Spanish gallery owner, Joan Miró, once visited my studio while I was working on the large figure painting "The Eastward Flowing River." Because rice paper wrinkles when hung on the wall, he was puzzled as to why a finished painting on rice paper would appear flat and clear when mounted on a large board. He asked, "How can a piece of paper become a work of art?" If you talk to him about mounting, he won't understand. It's the Chinese language and standards, or the Chinese materials, that shape Chinese art. In terms of Eastern and Western art education, I think Pan Tianshou did something particularly well: he advocated for Chinese painting to exist independently, away from Western painting.

The Paper: He rectified the chaos in the art academy education system at that time, but it was too difficult because he actually came from the literati painting system.

Yuan Wu: I don't think we are literati painters anymore. First of all, literati paintings must have the sentiments of literati. I have always thought that from 1949 to today, Chinese figure painting has really made progress. From Xu Beihong and Jiang Zhaohe to Fang Zengxian, Zhou Sicong, Lu Chen, and even Wang Ziwu, they are all excellent, and the historical period they lived in was more difficult than mine.

The Paper: Two years before Mr. Fang Zengxian passed away, The Paper interviewed him. He once said that it was a pity that he did not spend enough time on calligraphy when he was young. In his later years, he had been thinking about the creation of calligraphy and figure painting.

Yuan Wu: His calligraphy is far superior to ours, which is a shame. Fang Zengxian and Lu Chen were the figure painters who practiced calligraphy the most. In Lu Chen's later years, when I invited him to teach us, I saw a wall of calligraphy at his house. We simply can't achieve Lu Chen's calligraphy. Another point: modern Chinese painting isn't necessarily a fusion of poetry, calligraphy, painting, and seal carving. Our generation has new research topics in figure painting, as Jiang Zhaohe, Fang Zengxian, and Lu Chen have already taken modern Chinese figure painting far beyond its current boundaries.

The Paper: I saw that you exhibited "Farming on Zhu Da's Landscape," which seems to be a reflection of your own experience. Although you said that traditional poetry, calligraphy, and painting are distancing themselves, their spirits are in harmony.

Yuan Wu: Increasing distance doesn't mean giving up. It's like when you're carrying a ladder up a building. You have to go through three floors to get to the seventh floor. Can you still say you don't want the third floor? How could that be possible?

The Paper: Just like what you said about leaving blank space and making choices, your temperament and aura are all related to Chinese culture and Chinese aesthetics.

Yuan Wu: Leaving a large amount of white space is a very important Chinese aesthetic.

The Paper: I see that you have painted a lot of literati-style figure paintings before. Are you still painting now?

Yuan Wu: Actually, I am still painting. My next exhibition will be at the Shanghai Chinese Painting Academy. All the works will be by famous people, from ancient Su Shi, Bada Shanren, and Shen Zhou to modern Hu Shi, Lu Xun, Liang Qichao, and Lin Fengmian, all of whom are sages.

The Paper: In fact, if you want to paint Su Dongpo, you have to understand his works in order to capture his spirit.

Yuan Wu: I particularly like Su Dongpo. I have a large number of paintings of Su Dongpo. Among the ancient people, I painted Su Dongpo and Du Fu the most.

The Paper: You modestly say that your paintings are not literati paintings, but I always feel that they have a literati temperament. Mr. Liu Danzhai from Shanghai also likes to paint literati from all dynasties.

Yuan Wu: There are several painters in Shanghai whom I particularly admire, such as Liu Danzhai, He Youzhi, and Cheng Shifa.

The Paper: When I look at your line drawing works, I find that He Youzhi’s influence is very strong.

Yuan Wu: Yes, I particularly like his line drawings and copied many of his comic strips when I was a student.

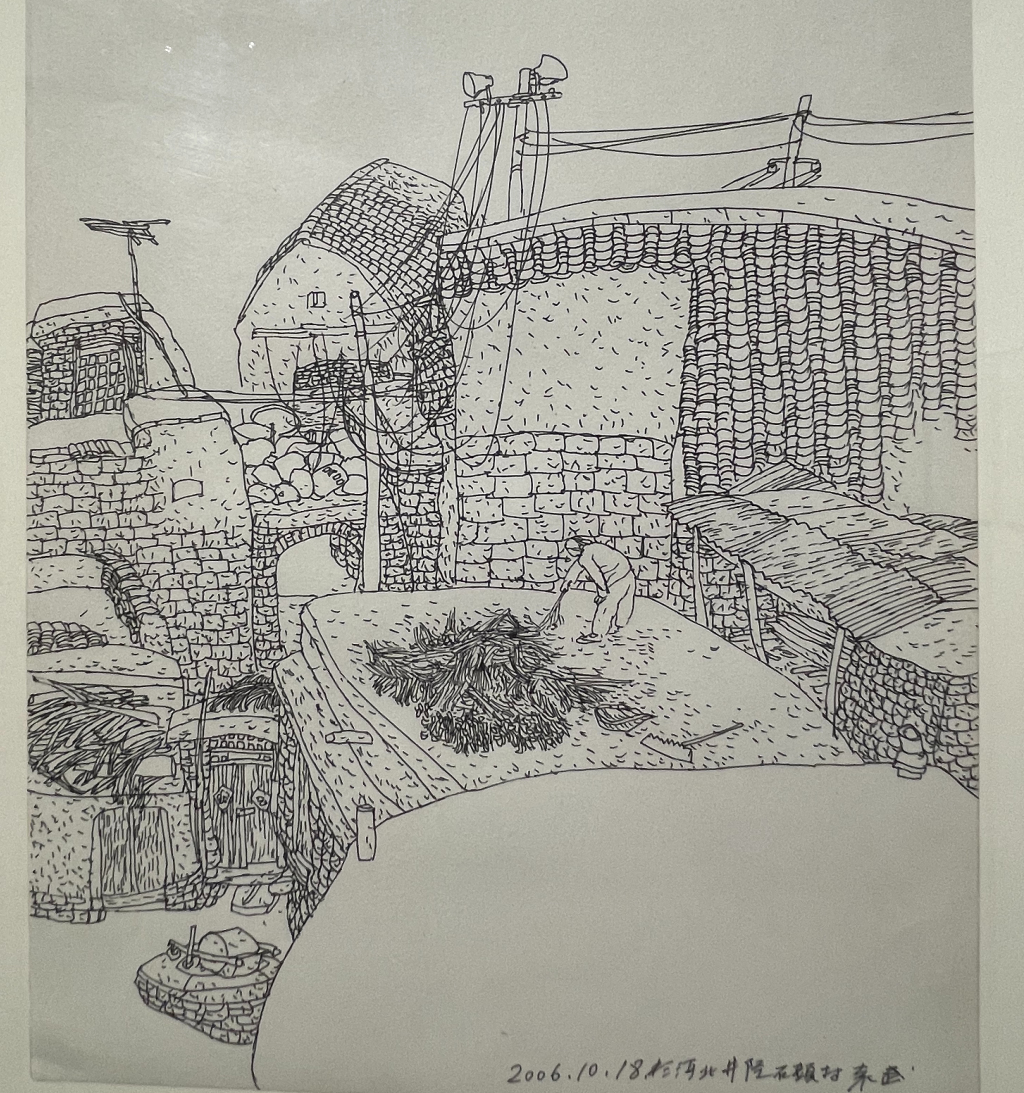

The Paper: Including your sketches exhibited this time, there are shadows of him, and of course, the shadow of Mr. Yuan Yunsheng.

Yuan Wu: When I was in college, I liked Yuan Yunsheng’s line drawing series “Yunnan Sketches” and copied one every day. At that time, I didn’t know how big the original was. I copied it every day with the newspaper “Changchun Daily” subscribed by our class. Because I used a direct brush to copy sometimes I couldn’t copy accurately, so my classmates joked with me, saying, "Xiao Yuan, are you revising Lao Yuan’s paintings?" When I was in college, I didn’t make drafts for sketches. I just used a direct brush to exercise my eyes.

The Paper: Train your eyes to be sharp.

Yuan Wu: Yes. Some people use charcoal, others light ink for drafting. I did the same at first, but later I learned from Jiang Zhaohe to use a brush with straight strokes. This is because as long as you keep moving, your emotions become focused, and your brushstrokes and observations become certain. Speaking of He Youzhi, for example, I copied one of his paintings, "The Great Changes in a Mountain Village," every day. His approach to each page was like a director's, and it has left a deep impression on me. Liu Danzhai, He Youzhi, and Cheng Shifa have all had a significant influence on me. Fang Zengxian and Lu Chen, because they practiced calligraphy, use dry and wet, thick and thin brushstrokes to create shapes that have a calligraphic quality. We can't achieve that.

Sketch of Yuanwushan Village

The Paper: There is actually a sense of writing in your works.

Yuan Wu: But my calligraphy is not good, so I cannot be so free. I now feel that the biggest problem with my painting is that I cannot relax and be free. I think that is a standard that is desirable but not pursued.

The Paper: Speaking of pine trees painted in brush and ink, Qi Baishi comes to mind. The Beijing Painting Academy has a permanent exhibition of Qi Baishi’s works.

Yuan Wu : Qi Baishi's greatest influence on me was during my time at the Beijing Academy of Fine Arts. I joined the academy at the age of 50. Our art museum has a permanent Qi Baishi Art Museum within a museum, where his works are permanently on display. I'd go upstairs during my lunch break to see them, sometimes just one painting. Qi Baishi was a true painterly genius, possessing a natural sensibility, passion, and ingenuity. Although he came from a peasant background, he was also a scholar, so his work is incomparable.

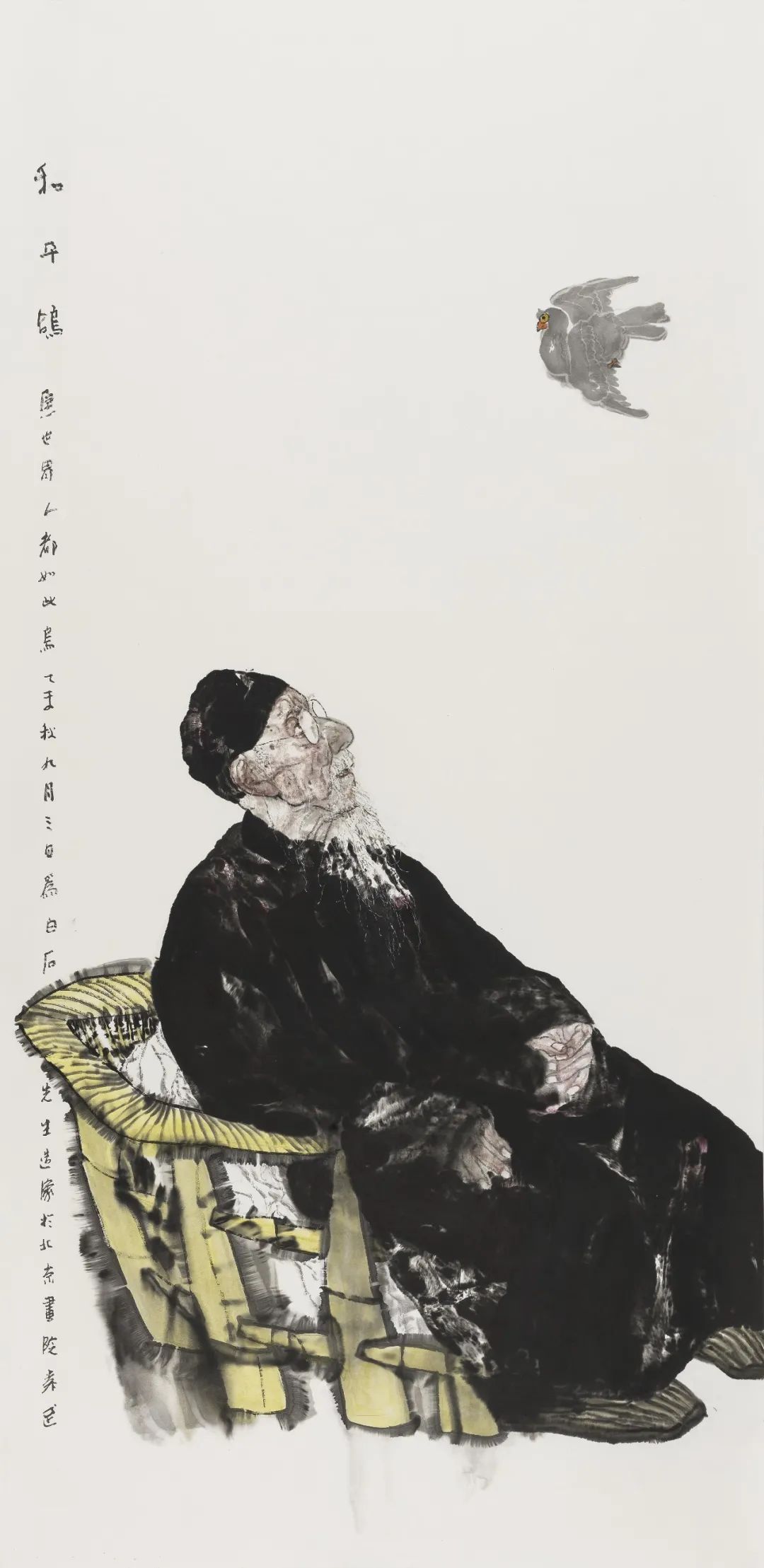

Peace Dove

The Paper: In fact, in your works, many compositional choices also have the shadow of Qi Baishi.

Yuan Wu: Yes, I've taught this in class. I say composition is a crucial part of creative work. Many people come up with an idea and immediately start painting it from a photograph. I say that no matter how many paintings there are in a museum, the first one to catch your eye is the one with the best composition, the one with a unique composition. A mediocre composition won't be appealing. Only by carefully considering the differences between reality and illusion, and choosing between the two, can we achieve the unity of content and form in a painting. This is the work of art beyond the painting itself.

The Paper: Speaking of skills beyond painting, although there are many large paintings on display this time, the scholarly atmosphere is still very strong. How do you understand the skills beyond painting?

Yuan Wu: I believe that besides painting, a painter should also focus on cultivating knowledge in other fields; otherwise, they won't achieve much. Fang Zengxian once said something, perhaps inspired by Sun Tzu's Art of War, that says, "In painting, one must make friends far away and attack those near." I read his book, "How to Paint Ink Figures," when I was a teenager, and this quote has always stuck with me. Culturally speaking, as a painter, you need to make friends far away, draw nourishment from literature, poetry, and film, and you must find a field you enjoy exploring. I love movies and usually listen to film music while painting. I also enjoy novels; I've been reading a lot of them since college. I also enjoy two visual arts: sculpture and photography. I don't practice them directly, but I enjoy looking at their works. In my studio, almost half of my collection consists of sculpture and photography, primarily Western works, inspired by the volumetric nature of sculpture and the black-and-white contrast of photography.

The Paper : This explains why your paintings have such a strong sense of volume and monumentality.

Yuan Wu: In addition, I particularly like contemporary art. Although my paintings are not contemporary, nor can I paint abstract paintings, nor do installation art, I have many such picture albums and am often inspired by them because they can tell me that the boundaries of painting are very far, and they let me know where the boundaries of painting are.

The Paper: So I think some of your figure paintings are landscape paintings.

Yuan Wu: Exactly. We should make friends with those far away and explore those near. Things far away, like movies and novels, are more distant from Chinese painting in the visual arts, such as sculpture and contemporary art. A painter must have a core interest beyond their specialty. You can never explore this interest, but you must pay attention to it. I can't make movies, write novels, or create contemporary art, but this is the inspiration I receive when I gaze upon them from afar. It always inspires me. In fact, even a small reference to them can be a significant step forward in my freehand figure painting.

The Paper: So it’s no coincidence that when people discuss your paintings, they mention compassion, poetry, and profound reflections on life.

Yuan Wu: I read a lot of novels when I was 30, 40, and even when I was 50. After I turned 50, I became particularly interested in history, including modern history, the history of the Republic of China, and the history of the Cultural Revolution. I would be immersed in them almost every time I read. For example, the characters of the Republic of China and the Cultural Revolution, their ups and downs, and development directly influenced my historical perspective and my understanding of the world.

The Paper: This explains why your works contain so many touching things. They aren't intentional. They're the result of digesting life and then feeling the urge to express it.

Yuan Wu: Yes, where does the impulse come from? It's being moved and burning by what you know.

The Paper: There's a burning passion within me, gushing out. It's not hypocritical, but a genuine desire to express my innermost feelings. A true artist possesses talent, diligence, inner sincerity, and a broad vision—all of which are crucial.

Yuan Wu: Yes, sincerity is important. Don't be pretentious or let others tell you what to do. Try to create art independently. It can be immature or flawed, but that's fine. It represents my true inner thoughts, whether it's my feelings, my thoughts, or my style of expression. For example, for ten years now, I've been painting modern figures within traditional landscapes. Many people don't accept this, even saying that adding modern figures to ancient landscapes doesn't work. I argue that if ancient people could be added to landscapes, why can't I also add modern people? A hundred years from now, modern people will still be ancient. You call this clothing modern, but a hundred years from now, it will still be ancient. If people don't accept this kind of imagery, it simply means I haven't handled it well, and this kind of work needs to be refined and improved.

The Paper: So art is essentially temporal. A true artist must be embedded in time. Only sincerity and real skills can make you embedded in time - technology is also very important.

Yuan Wu: Yes, and time is a long river flowing by. Whether you are a small stone or a wave, or even nothing, depends on what traces you leave behind.

Exhibition site