The Frick Collection is a museum located in New York, USA. The museum houses the collection of industrialist Henry Clay Frick (1849-1919) and is famous for its outstanding European painting masters, sculptures and decorative arts. The Paper Art learned that now, flowers are blooming outside the Frick Collection on Fifth Avenue, and inside the museum, after five years of renovation and reconstruction, this venue is about to open to the public, presenting art masterpieces from the Renaissance to the 18th century to the public.

As one of the few remaining Gilded Age mansions in New York, the Frick Collection was built in 1914 and was once the residence of Henry Clay Frick. Frick loved art and collected a very rich collection of works throughout his life. After his death in 1919, his family donated the mansion, art collection and 15 million yuan fund to society in accordance with his will. In 1920, Frick's daughter Helen (Helen Clay Frick) established the Frick Art Research Library in her father's former mansion in memory of her father. As an important part of the Frick Collection. In 1935, the Frick mansion was transformed into a museum and opened to the public. The collection includes art masterpieces from the Renaissance to the 18th century. Currently, this venue is undergoing a $220 million renovation and expansion.

Frick Collection

During this time, the museum’s collection of masterpieces—including works by Bellini, Vermeer, Van Dyck, Rembrandt, Fragonard, Turner, and Whistler—was on rent at the Whitney Museum of Art a few blocks away, looking as charming as ever but a little lonely in the aesthetic gallery they call home.

Inside the Frick Collection

Inside the Frick Collection

Frick Collection

By this definition, the Frick Collection is a distillation of a particular history and sentiment, and the reopened museum retains familiar artworks while adding new features, most notably by converting the entire second-floor family room into an intimate gallery.

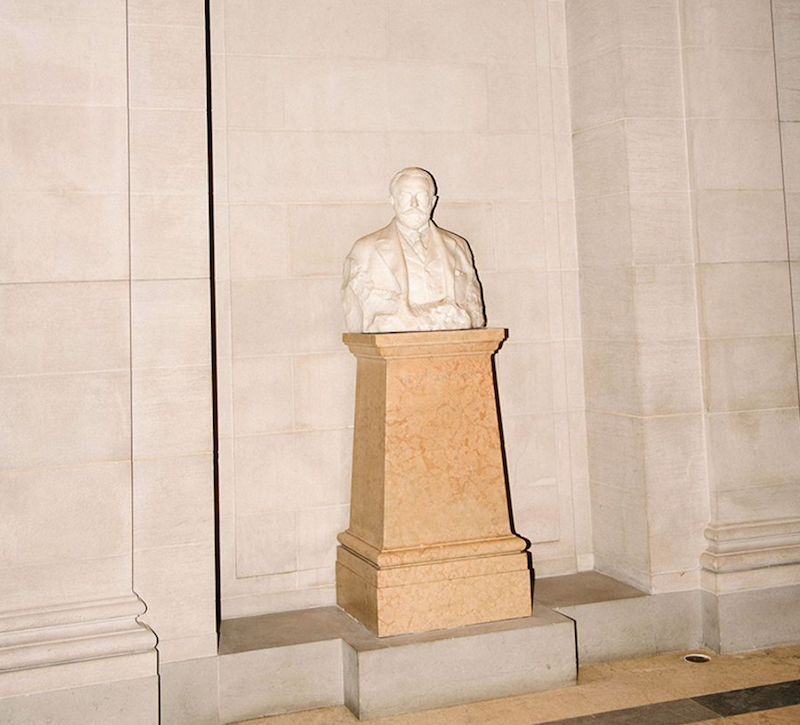

Statue of Henry Clay Frick

What does this particular collection memorialize? Some would say, of course, it memorializes one man: Henry Frick. He himself assembled the collection in just a few decades and gave it to the public. Like many art museums, the memorial celebrates the complex power of private wealth. Of course, Frick’s benevolent populism had serious limitations: he was a notorious and staunch anti-unionist in American labor history.

Adelaide Childers Frick

It is a story of taste during the Gilded Age of Europe and America (late 19th and 20th centuries), and of a family whose taste in art celebrated ideas of beauty. Frick's wife, Adelaide Childs Frick, was a lover of Rococo paintings and decorative arts, and their daughter, Helen Clay Frick, amassed a large collection of religious works from the early Italian Renaissance after her father's death.

Frick's daughter Helen Clay Frick

The Frick House is a large-scale "family" museum, a lifestyle museum. Whether it is the reception space facing the street or the lounge space upstairs, it is family-style. In 1935, when the house opened as a museum, it was officially transformed into a museum. Over the years, the museum has been expanded many times.

Enter the main entrance and look to the right. This is the new extension designed by Selldorf Architects and Bayer Blinder Belle Architecture and Planning. It includes a two-story reception hall, cloakroom, cafe and special exhibition hall. Here, "Vermeer's Love Letters" will be unveiled in June. However, if visitors choose the path on the left, they can lead to the original house facing Fifth Avenue in 1912.

Dining room

Describing his plans for his future home, Frick wrote that he envisioned "a house that is comfortable, well-appointed, simple, tasteful, and not ostentatious." Of course, unassuming is a relative term. He didn't have a ballroom, but he did have a bowling alley in the basement. Today, the bowling alley is still intact. He got everything he asked for, and added plenty of luxurious decoration. The dining room of the Frick House is the first major exhibition room a visitor encounters. It's simple and bright, and the high-ceilinged space has the atmosphere of an 18th-century English manor.

The Frick House's Dining Room

The female portraits of artist Thomas Gainsborough, a favorite of the Frick collection, shine here. The tall, supple, and peaceful figures of Lady Frances Duncombe and Peter William Baker set the noble tone for the room, while Gainsborough's ruddy, spirited Grace Dalrymple Elliott adds a sensual spark to the room.

Gainsborough's Grace Dalrymple Elliot

Gainsborough's Francis Duncombe and Mrs Peter William Baker

Fragonard Room

In the adjacent room, the drawing room of the mansion, there is a set of 14 paintings by the French artist Jean-Honoré Fragonard called "The Progress of Love". The works were originally four paintings commissioned by Madame du Barry, the lover of Louis XV. But for unknown reasons, Madame du Barry rejected the works. Fragonard kept the paintings and 20 years later, he created 10 more paintings on the theme in a self-commissioned manner.

Fragonard Room

By then, Fragonard had left Paris to escape the Revolution, and his new paintings had a hurried feel. Politically out of touch, they passed from one owner to another, eventually ending up in the hands of JP Morgan, from whose estate Frick bought them. He also bought many small decorative items, including Italian Renaissance bronzes, Chinese porcelain, and French enamels.

Fragonard: The Progress of Love

Fragonard's "The Progress of Love" in the exhibition hall

The Fragonard Room, which, with its vegetation and clouds, resembles a springtime snow globe, has long been one of the Frick Collection’s signature attractions, and along with the rest of the original house, forms the museum’s “Masterpiece Center.”

Living Hall

Living Hall

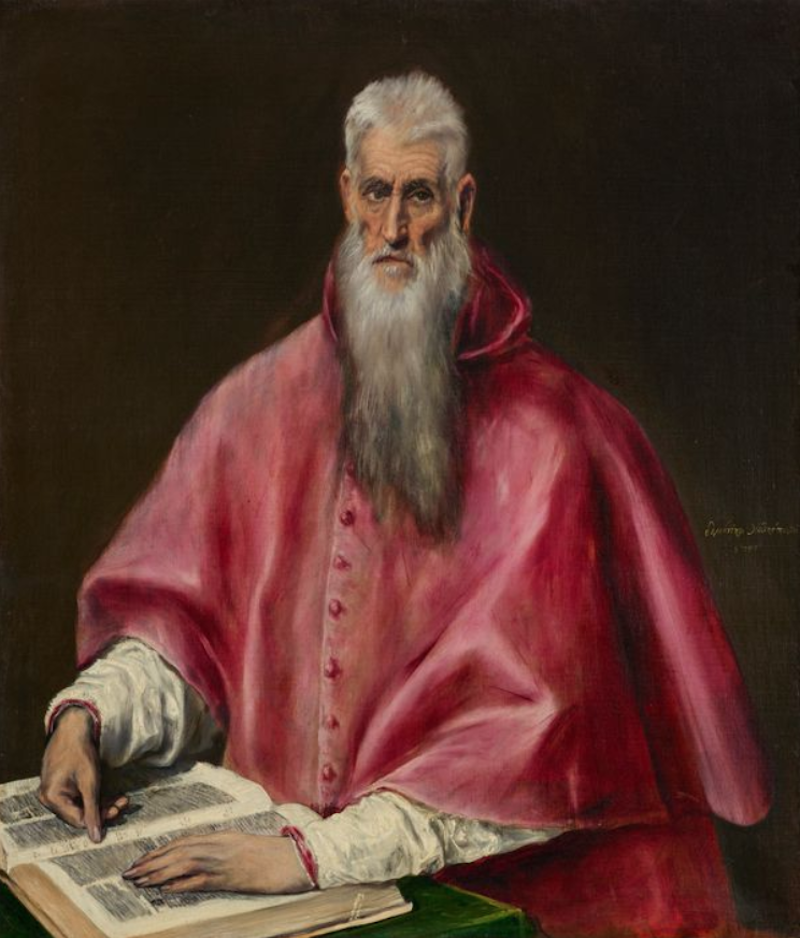

The Living Hall contains five great paintings from the 15th and 16th centuries, all displayed as Frick arranged them. He placed El Greco’s portrait of Saint Jerome, a gaunt fanatic in a pink robe, over the fireplace. On either side are Hans Holbein the Younger’s portraits of two English ideological warriors, one Sir Thomas More, who opposed the English Reformation, and the other Thomas Cromwell, who supported it. Cromwell played a major role in More’s political downfall and execution, but More won on the aesthetics of the portrait.

El Greco, Portrait of Saint Jerome

Hans Holbein the Younger, Portrait of Sir Thomas More

Hans Holbein the Younger, Portrait of Thomas Cromwell

Directly across the room is Giovanni Bellini's panoramic painting St. Francis in the Desert (c. 1475-1480). It was one of the few religious paintings Frick purchased, and he seemed to love it. Who wouldn't? The birds in the trees, the donkeys in the fields, the shadows of the clouds, the painting shows both the sacredness and wonder of nature and the holiness of human beings. The only work that rivals this marvelous painting is in the West Gallery.

Giovanni Bellini: Saint Francis in the Desert

West Gallery

The West Gallery is a room as long and wide as an airport runway, built specifically for art. In 1915, it was the largest private gallery in New York City, and it houses some of the most beloved treasures from the Frick Collection. Ninety years later, they remain here.

West Gallery

Frick was particularly fond of portraits, especially of pretty women and voluptuous men. This is the case with Anthony Van Dyck’s 1620 portrait of the Antwerp artist Frans Snyders, a painter of plants and animals who was as famous as Peter Paul Rubens. In history books, he ranks second only to Rubens, but Van Dyck made him into a fashionable dream man. When Rembrandt completed his huge self-portrait in 1658, he was already in the twilight of his career. But he still looks like a star, dressed in rich scarlet and gold, holding a scepter-like staff, his face half-lit, half-shadowed, with a faint smile.

Anthony van Dyck, Portrait of Frans Snyders

Velázquez: Portrait of Philip IV, King of Spain

Velázquez's 1644 Portrait of Philip IV of Spain is a true royal: a strong man at the height of his power, wearing a coat of silver filigree. Frick's collection of Spanish art was modest, but the Spanish art he did collect put him ahead of other industrialists.

In 1914, Frick bought Goya’s massive painting The Forge (1815-1820), which put him a step ahead of other industrialists. The painting depicts three burly, hunched, ragged workers hammering at a red-hot sheet of metal. It seemed an unlikely subject to interest him, especially given his complicated relationship with labor politics. But he saw immediately the role of the blast furnace in painting, and this painting does just that.

Goya's The Blacksmith

Frick’s interest in Vermeer was also unusual. At the time of his acquisition, the Dutch Golden Age painter was not as famous as he is today. Frick owns three Vermeers. Two smaller ones hang in a narrow corridor near the garden courtyard added by architect John Russell Pope in the 1930s, and the largest, Mistress and Maid (1666-67), hangs in the West Gallery. It was also the last painting Frick bought.

Vermeer's The Mistress and Her Maid

It is worth mentioning that Isabella Stewart Gardner of Boston, a rival of Frick, had bought a Vermeer painting in 1892, which won the Vermeer auction. Isabella bought The Concert, but it was stolen in 1990 and its whereabouts are unknown.

Second floor of the collection hall

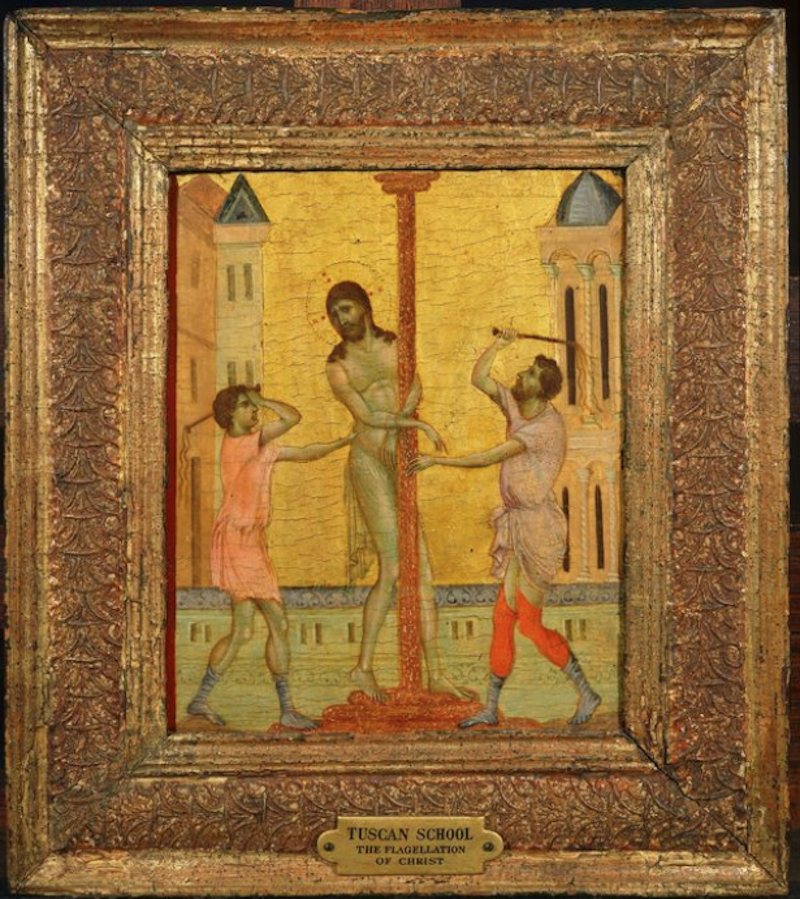

There used to be a masterpiece in the doorframe at the end of Fifth Avenue, as you looked down from the West Gallery: Piero della Francesca’s “St. John the Evangelist.” It was one of the early Italian altarpieces Helen Clay Frick acquired after her father’s death. She acquired other altarpieces by Cimabue and Duccio, Gentile da Fabriano and Paolo Veneziano, and placed them in a small room that was once a private office.

Cimabue's Altarpiece

Duccio's Altarpiece

When the collection reopened, this section was moved to the first floor, the original family home, which visitors can reach via two staircases: the grand staircase, carved from five-coloured marble, original to the house, and the additional staircase from Selldorf that leads to the second floor from the new wing.

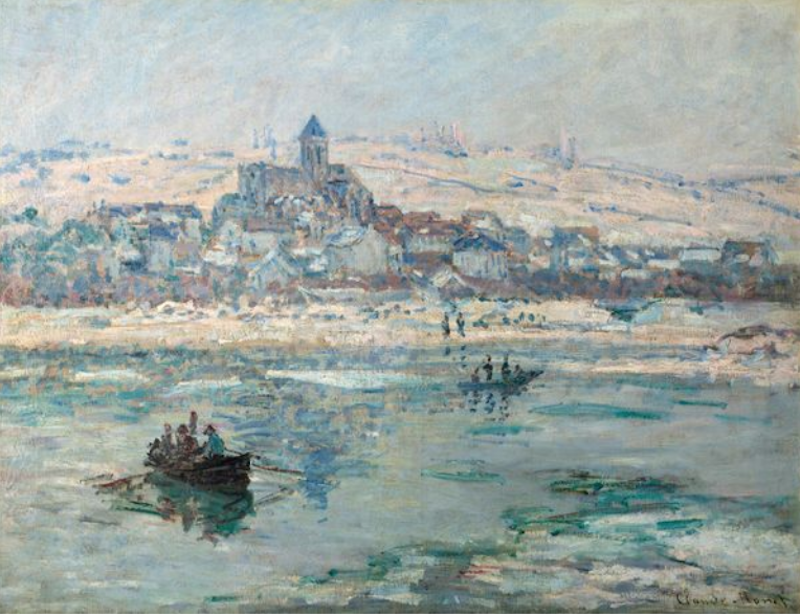

Stairs leading to the second floor

After Frick’s wife, Adelaide, died in 1931, much of the second floor was converted into staff offices. Now, 10 of the rooms—bedrooms, living rooms, guest rooms—have become galleries, some of which display art from Frick’s time. This was once the family’s breakfast room, and it looks much as it did when they gathered in the morning for coffee. The walls of the room are covered in newly woven silk damask, on which hang landscapes by Corot, Daubigny, and Troyon. These small-scale Barbizon landscapes inspired Henry Frick’s collecting passion. A few steps away, in a room of comparable size, visitors can see Frick’s early interest in modernism. He collected small-scale works by Monet and Manet.

Corot "The Lake"

Claude Monet: Vétheuil in Winter

Manet's Bullfight

In fact, the biggest benefit of having the second floor as an open space is that it allows for the exhibition of lesser-known parts of the museum’s collection. Visitors can admire the museum’s collection of clocks and other art treasures. But what is particularly touching about the second floor is the sense of presence it evokes of its original occupants. Helen Clay Frick’s Italian Renaissance collection was displayed on the first floor for ninety years. Today, 15 paintings are on display in her bedroom. Two works are temporarily not at home, a Cimabue on loan to the Louvre and a Duccio on display in the special exhibition “Siena: The Rise of Painting.” However, Piero’s work is here, between two windows. Paolo Veneziano’s “The Coronation of the Virgin” is also here.

Paolo Veneziano: The Coronation of the Virgin

Collection of clocks

Bouchet Hall

In contrast, the Boucher Room, named for the group of allegorical paintings by 18th-century French court painter François Boucher (1703-1770) that hang on its walls, was once Adelaide’s private sitting room. After Adelaide’s death, the room was disassembled and moved downstairs for public viewing, but now it has returned with details that she no doubt enjoyed every day: Sèvres porcelain, Rococo-style furniture, and soft 18th-century wooden floors.

Bouchet Hall

Boucher's Arts and Sciences

Henry Clay Frick's bedroom

Of all the spaces on the second floor, the one that best reflects Henry Clay Frick’s personal style is a dark-wood walnut room that was once Frick’s bedroom. However, the furniture here is not original. The most important work of art here, a portrait of Louise de Broglie (the Countess of Hausonville) by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingre, was not in his collection. It was acquired eight years after his death.

Henry Clay Frick's bedroom

Ingres: Portrait of the Countess of Hausenville

The image of the Countess has long been the mascot of the Frick Collection, the image of the museum that everyone identifies with. So it makes perfect sense to put it here. But the Frick did choose a painting for this room, and it’s right in the center of it.

This is Emma Hart, later Lady Hamilton, a portrait painted by the English artist George Romney in 1782. It shows a smiling young woman dancing against a distant landscape and a dawn (or perhaps sunset) sky, holding a small dog in her arms. It was not a masterpiece in the collection, but it was one of which Frick was privately most proud, and he kept it almost reverently, framed in a wreath of carved wood leaves, above his fireplace, directly opposite his bed, as if to see it first thing every day and last thing every night.

George Romney, Emma Hart, Later Lady Hamilton

There is evidence that as he aged and his health declined, Frick spent more and more time alone with his art. In the book The Fricks Family Collection: The Taste and Evolution of an American Family in the Gilded Age, former collection curator Ian Wardropper says Helen remembers finding her father alone, lying on a couch in the West Gallery, quietly contemplating the paintings there, a week before his death.

Xavier Salomon, the collection’s chief curator who oversaw the gallery’s installation, has suggested that Emma Hart’s face was the last Frick saw, as he died in bed in this room.

A poet wrote: "All we have left is love." Many people say that Frick is a cold machine, but he seems to have poured all the passion he could possibly give to human beings into art. And this artistic passion of Frick created his museum. This museum is loved by many people and continues to grow.

Rembrandt's Portrait of Nicolas Root

Constable's The White Horse

Saint Francis Ivory Sculpture

This is a tour of the Frick’s collection, and you’ll also see Rembrandt’s Portrait of Nicolaes Ruts and Constable’s panoramic landscape The White Horse, acquired the same year. There’s also a ivory carving of St. Francis from northern France, acquired last year. Dating from around 1300, it’s one of the oldest objects in the Frick’s collection. But it’s also new, like the reinvigorated museum itself.

Frick Collection

The Frick Collection will open to the public on April 17.

(This article is translated from The New York Times, author Holland Cotter, photography Adrianna Glaviano)

NcvyFL Gjt ilLd VmMZ xYWMrJU