"The midnight sun shines, but noon is dark... the aurora burns between the stars, the storm and the waves... the fog almost condenses into a solid, covering the whole world in an instant." This is how Anna Boberg described her experience painting in the Norwegian Förden Islands in the early 20th century. This description also fits the theme of the exhibition "Northern Lights" currently being held at the Beyeler Foundation in Basel, Switzerland.

The exhibition presents 74 landscape paintings created between 1888 and 1937 by Nordic and Canadian artists such as Tom Thomson, Hilma af Klint and Edvard Munch, presenting a raw, brilliant and magnificent natural drama.

Tom Thomson, Aurora Borealis, c. 1916-1917 © National Gallery of Canada

The northern forests are a common source of inspiration for the artists in the exhibition. Natural phenomena such as the seemingly endless forests, endless summer light, long winter nights and the northern lights have given rise to a specific form of Nordic modern painting that continues to exert an enduring appeal and fascination.

At the entrance to the exhibition, Munch's Children in the Forest invites viewers to stand with six tiny figures at the edge of a sunlit forest, looking up at a forest of trees that tower like giants - transformed into mask-like faces, animal muzzles, circling arms, and even a giant boot. Will these children bravely step in, or will they shrink back?

Edvard Munch, Children of the Forest, 1901-1902 © Munch Museum

Like a stage set for the Brothers Grimm fairy tale Hansel and Gretel, this 1901 painting shows nature as a mysterious and mythical force, a space for both psychological exploration and physical adventure.

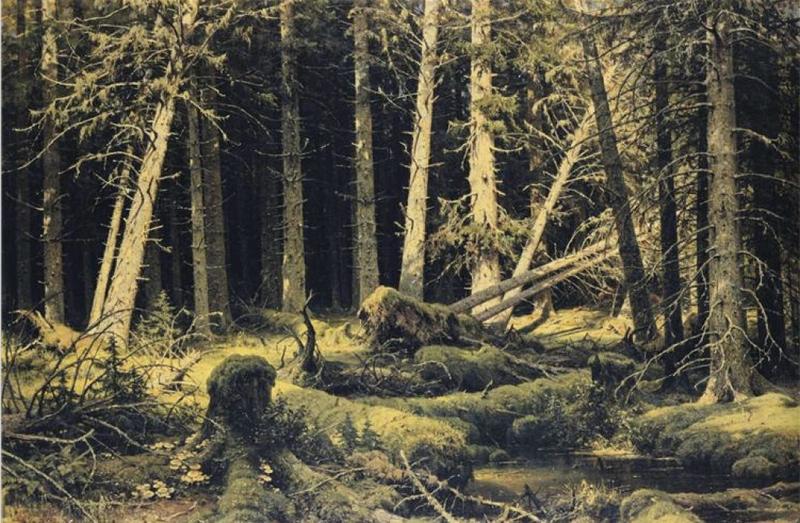

Ivan Shishkin, A Tree Blown by the Wind, 1888

What follows is a series of magical images of light and shadow. Ivan Shishkin’s Wind Fallen Trees (1888) draws the viewer into a vast and deep charcoal forest with bright white tree trunks. Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s Mantykoski Waterfall (1892-1894) uses abstract golden lines to outline the icy rapids. And in Lair of the Lynx (1908), he depicts the scene of deep winter in Karelia, Finland, after a hunting trip: fluffy snowdrifts and colorful shadows. In this land of pine, spruce, and larch that straddles the border between Finland and Russia, Gallen-Kallela, a fighter in the Finnish War of Independence, sought to establish a national artistic style, while Shishkin, the “Forest Tsar,” insisted that his epic scenes showcase “vastness, space, land… This is the wealth of Russia.”

Akseli Gallen-Kallera, The Lynx's Lair, 1908

Harald Sohlberg’s Country Road (1916), aglow in the midnight sun, is paired with the magnificent Winter Night in the Mountains (1901), which depicts the peaks of the Rondane mountain range gleaming in the twilight – the setting for Ibsen and Grieg’s Peer Gynt. Gazing at the mountains, Sohlberg wonders how “lonely and insignificant I am in the infinite universe”, but also feels “as if I had suddenly woken up in a new, unimaginable and inexplicable world”.

Harald Solberg, Country Road, 1916

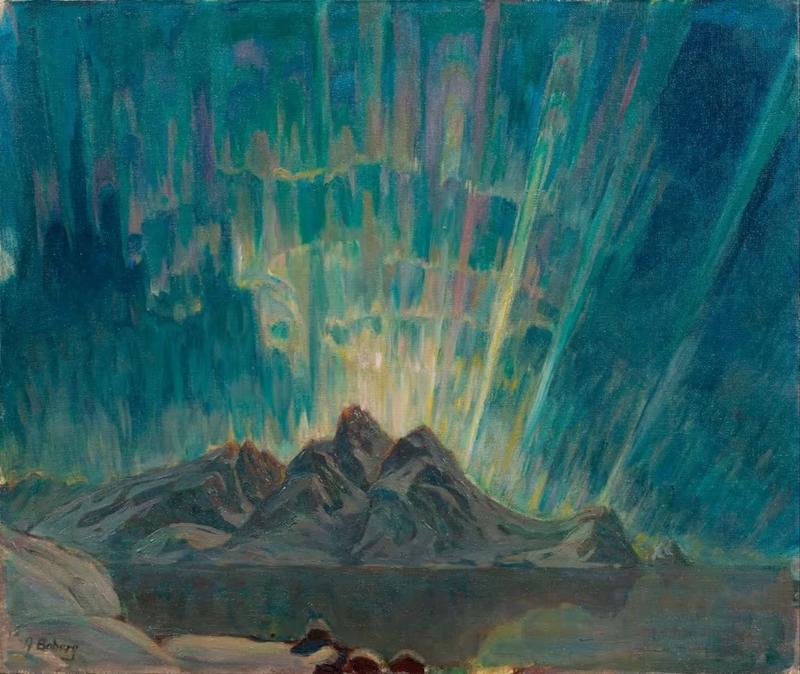

The dazzling splendor of the Aurora Borealis is both a visual motif – Anna Bobel paints them as ghostly turquoise and magenta curtains pouring over the Arctic Ocean, while Tom Thomson lights up the night sky over Ottawa with ghostly lime-green pillars – and a symbol of artists’ imaginative transformation of boreal forest landscapes. Between 1880 and 1930, northern landscape painting enjoyed a golden age, when geographical and political factors – the flight from industrialisation to untouched nature, the start of polar exploration, the rise of romantic nationalism – coincided with aesthetic opportunities, as the influence of French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism spread across the globe.

Exhibition site

The Fondation Beyeler has long excelled at recalibrating the narrative of modernism, bringing artistic perspectives from the margins into the mainstream, and the exhibition highlights the personal styles of more than a dozen artists through independent exhibition spaces. Bobel, for example, is little known outside Scandinavia: the wife of a Stockholm architect, she used to tie her easel and frame to a heavy fur coat, painting outdoors and depicting dizzying close perspectives with Monet-like persistence, such as the transparent and borderless "Glacial Lake."

Anna Borberg, Aurora Borealis, Study from Northern Norway © National Museum, Stockholm

On the other hand, there are artists who were once active in the international art world but have been forgotten by the Paris-centric history of modern art. For example, the Swedish painter Gustaf Fjaestad combined his meticulous observation with the decorative curves and rhythmic dots of Art Nouveau in his Frozen Trees at Dusk (1913). These works come from the collections of the Belvedere Palace and the Musée d'Orsay in Vienna - Fjaestad was a darling of European collecting before the First World War.

Gustav Fiesta, Newly Fallen Snow, 1909 © Belvedere Palace, Vienna

In 1912-1913, an exhibition of Scandinavian art that toured the United States (including works by Fiesta and Solberg) was shown in Buffalo, attracting the attention of Canadian artists, including the wealthy businessman Lawren Harris, who subsequently founded and funded the Canadian modernist art group the Group of Seven and supported two Canadian artists, Tom Thomson and Emily Carr, whose works were more self-consciously abstract than those of European painters, while still deeply rooted in their beloved landscapes, giving them an exhilarating intensity.

Exhibition site

Carr’s Forest, British Columbia (1931-1932) depicts the feeling of a storm sweeping through the forest with swirling, dynamic lines, and in Inside a Forest (c.1935), Sunlight in the Woods (1934), and Dancing Sunlight (c.1937), she brings the forest to life with dazzling swirls of white, as if the wind is howling through the canvas. As an environmentalist concerned with industrial logging, Carr painted in a trailer, diluting her oil paint with gasoline to create fluid, lifelike works on cheap Manila paper. She could greatly simplify forms—Abstract Tree Forms, 1931-32, and the repetitive triangles of Reforestation, 1936—but never gave up what she called “the form of the earth, the density, the juice of the grass. I wanted its volume, and I wanted to hear its pulse.”

Lauren Harris, Mountain Form, ca. 1926

Harris also initially painted in a lyrical style—his Fantasy of Snow (c. 1917), with its branches bearing a shifting iridescent sheen, could be seen as a stylized version of Fiesta’s decorative tapestry Moonlight on a Winter Night (1895), which he exhibited at the Buffalo exhibition. Eventually, however, Harris decided that Canada’s unique landscape—“the vast North and its vivid whiteness, its loneliness and abundance”—required a different artistic response. In Beaver Pond (1921), trees, foliage, and reflections in the swamp are sharp and clear; while in Lake Superior (1919) and Mountain Forms (c. 1926), hard peaks and black waters are reduced to angular, flattened forms that gleam like metal—a new, crystalline aesthetic of the North American sublime.

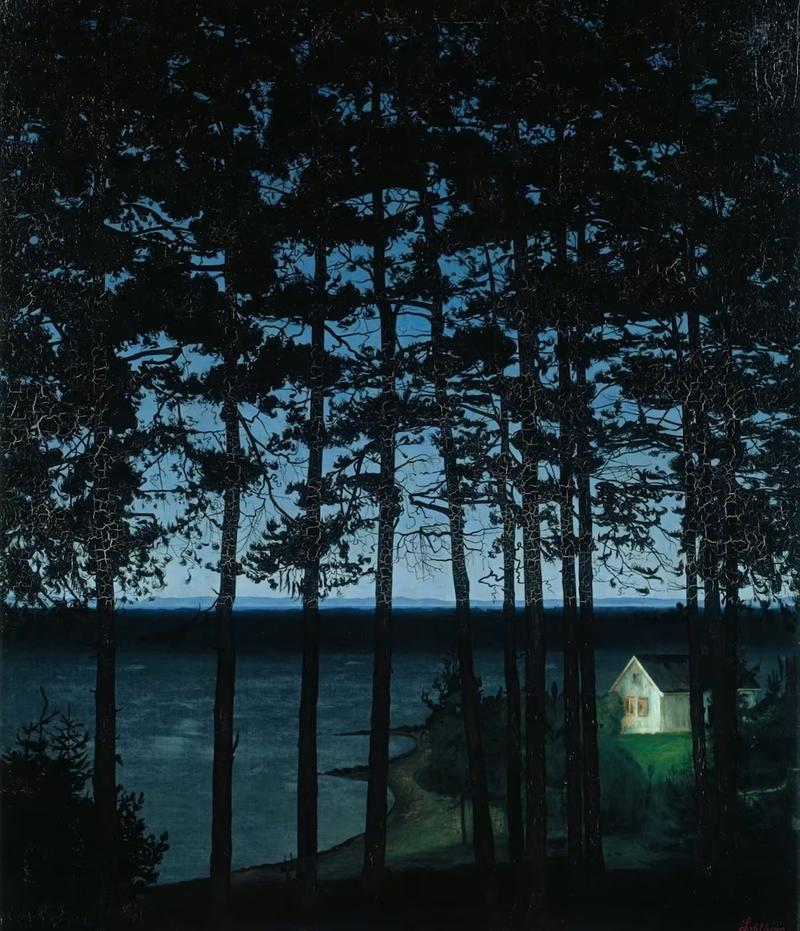

Harald Solberg, House on the Coast (Fisherman's Hut), 1906 © Art Institute of Chicago

The most fascinating transatlantic artistic inheritance comes from Solberg’s noir-style House on the Shore (1906), which depicts a lonely beach hut vaguely visible through the shadows of trees and has been exhibited in an American exhibition. John Thomson’s linear, melancholic River of the North (1915) depicts an autumn landscape in Algonquin Park and reflects the same image on the water, trembling behind the crisscrossing network of trees. This anxious and fascinating work by the young painter evokes Eliot’s poem in The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, published that same year: “As if a magic lantern, it casts on the screen a nervous pattern.”

Tom Thomson, The River of the North, 1915 © National Gallery of Canada

The sense of alienation in Thomson’s work (lattice-like compositions, pergolas, grids of rows of trees) profoundly influenced the painter Peter Doig in the 1990s. Thomson’s Canoe (1914) shows another theme inherited by Doig: a white boat lying empty on the shore. It was from such a boat that Thomson drowned in 1917.

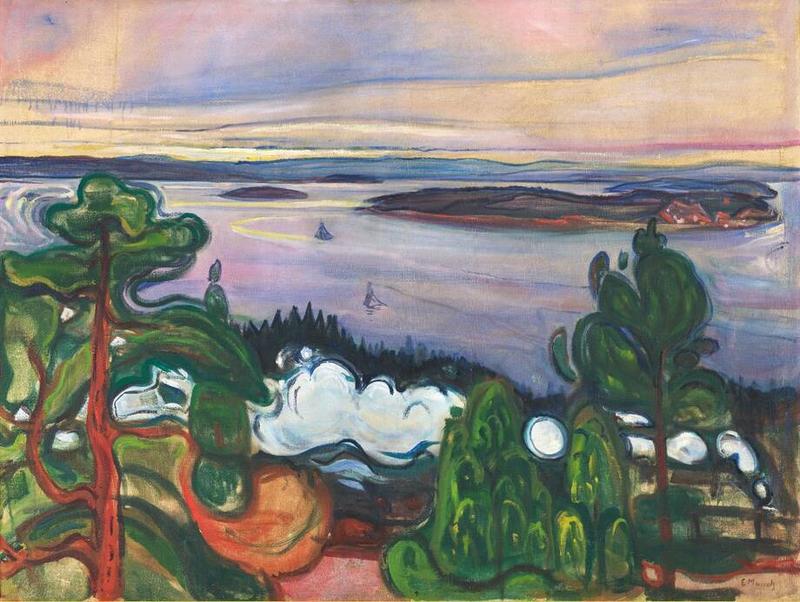

Munch, Train Smoke, 1900

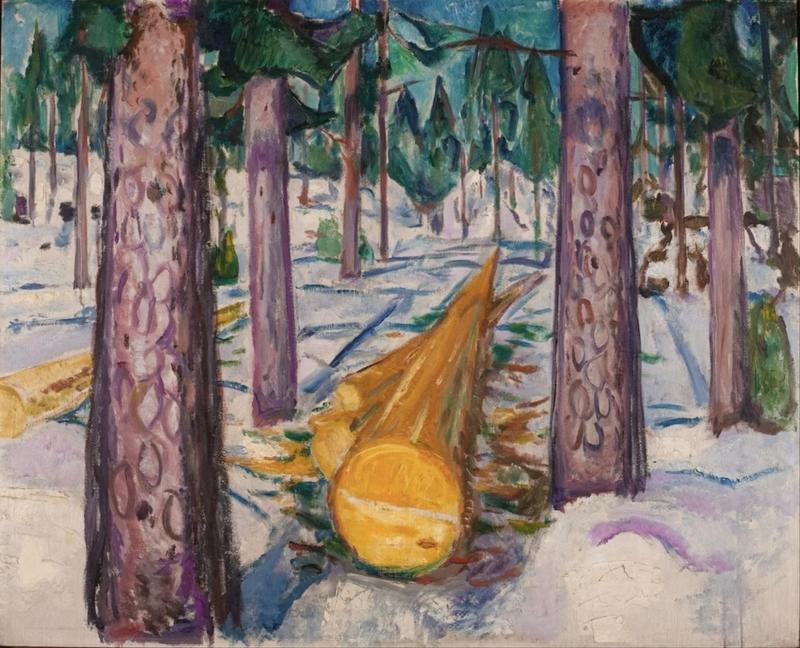

For European audiences, Thomson was the unforgettable discovery of the Fondation Beyeler, but even the exhibition’s most famous artist, Munch, offers an unexpected surprise: his landscapes seem so alive after the doom-laden figures disappear. White Night (1900-1901) depicts an insomniac’s vision of jagged, jagged spruce trees lining an icy fjord. In Starry Night (1922-1924), a blue sky swirls and swirls, shrouding the painter’s shadowy, mysterious form. In Train Smoke (1900), a streamer of steam swirls like a cheerful flag around a leafy tree, set against a lavender pool. And the wildly coloured, free-handed Yellow Log (1912) – lying in a snow-covered purple forest, glows from the central gallery; it is the successor to David Hockney’s fallen trees at Woldgate.

Edvard Munch, Yellow Logs, 1912 © Munch Museum

Although this work has been around for a hundred years, the shadow of contemporary art often comes to mind. It also reveals how painting, as a continuum that spans continents and time and space, continues and evolves between the past and the present.

Exhibition site

Note: This article is compiled from the Financial Times and the exhibition website. The exhibition will last until May 25

- mekyVPdOk04/01/2025