"Like a mayfly in the universe, like a grain of sand in the vast ocean" - this famous line from "Red Cliff" written by Su Dongpo in Huangzhou in the Song Dynasty, with its great sense of time and space travel and vastness, has influenced countless Chinese literati for thousands of years. So much so that more than a hundred years ago, a teenager came to Shanghai from Changzhou, the place where Dongpo died, and resolutely changed his name to Liu Pan, taking two characters from "a grain of sand in the vast ocean".

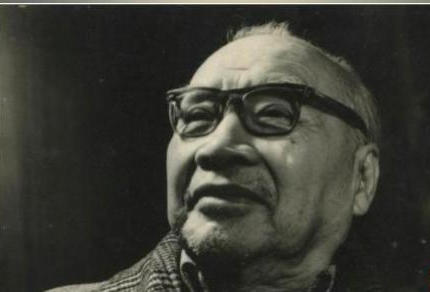

This was Mr. Liu Haisu, who later had a great influence on the history of modern and contemporary Chinese art.

This name change shows his feelings. Throughout his life, Su Dongpo's personality, thoughts, poetry, calligraphy and painting had a profound influence on Liu Haisu. His calligraphy and thoughts were passed down from generation to generation, and they were a huge spiritual support for Liu Haisu, especially when he was in difficult circumstances.

Detail of "Portrait of Su Shi" (painted by Zhao Mengfu)

Liu Haisu

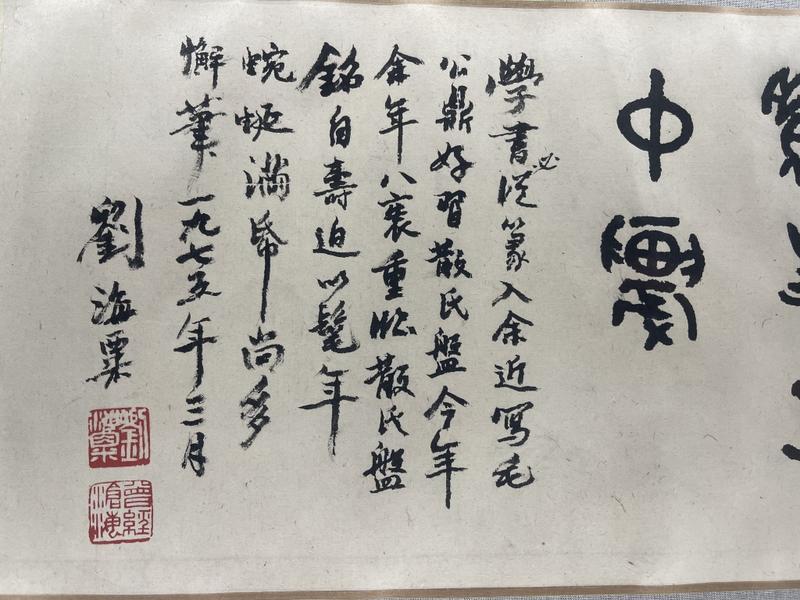

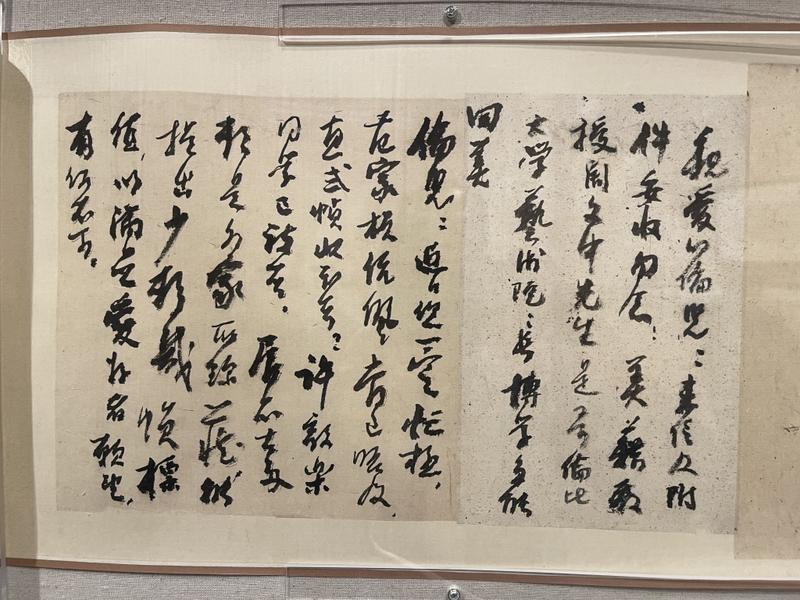

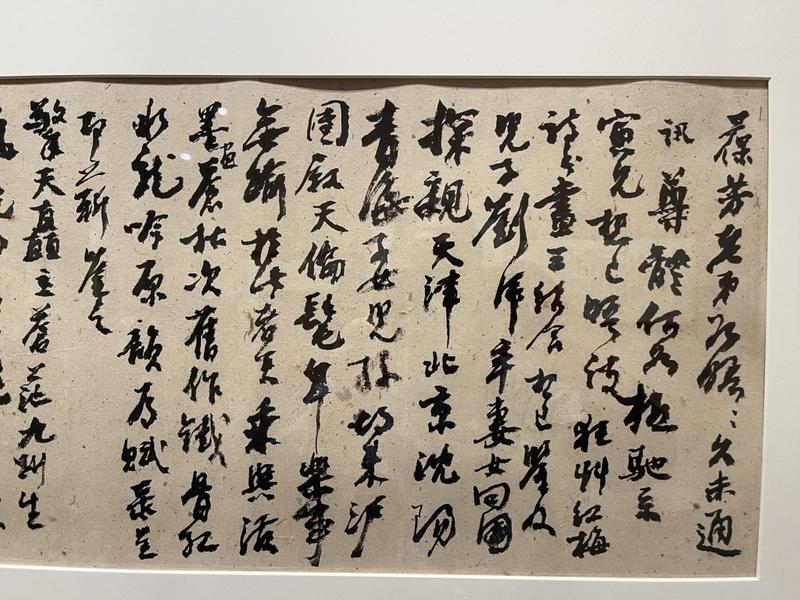

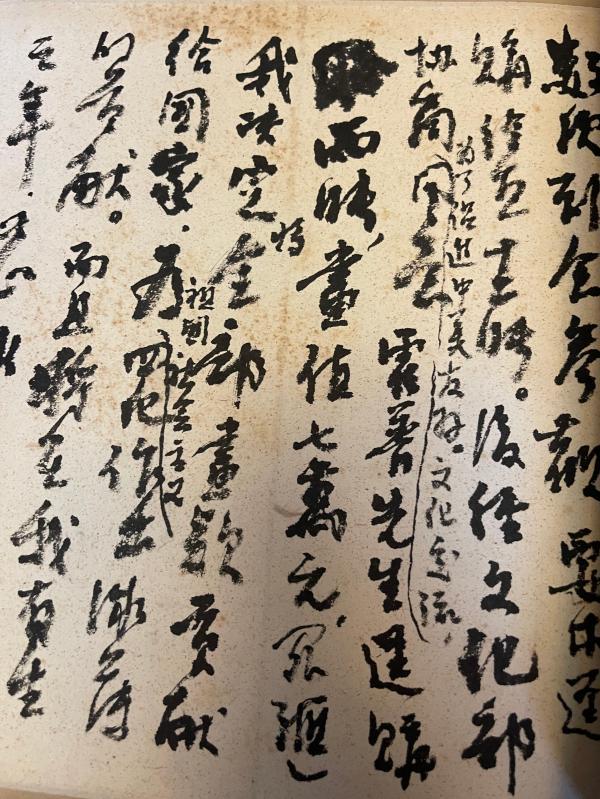

Similarly, both Liu Haisu and Su Dongpo became famous at a young age, but fell into the trough of life in their middle and old age. Huangzhou after the Wudai Poetry Case was the darkest moment in Dongpo's life, but it was also the place of his nirvana and rebirth. In the 1950s and 1960s, Liu Haisu fell to the bottom of his life due to his outspokenness in Shanghai, which led to the hardships of political movements in the second half of his life. He then turned to inner artistic cultivation. In addition to painting, he devoted more attention to calligraphy, integrating inscriptions into calligraphy, and practicing bronze inscriptions, the so-called "gathering vitality and letting it run in my wrist." Finally, around 1975, his calligraphy truly reached its peak, which can be seen particularly in his letters. It can even be said that the calligraphy in the letters around 1976 can be compared to Dongpo's "Huangzhou Cold Food Poems", witnessing the inheritance and fortitude of Chinese literati in the face of huge adversities in life.

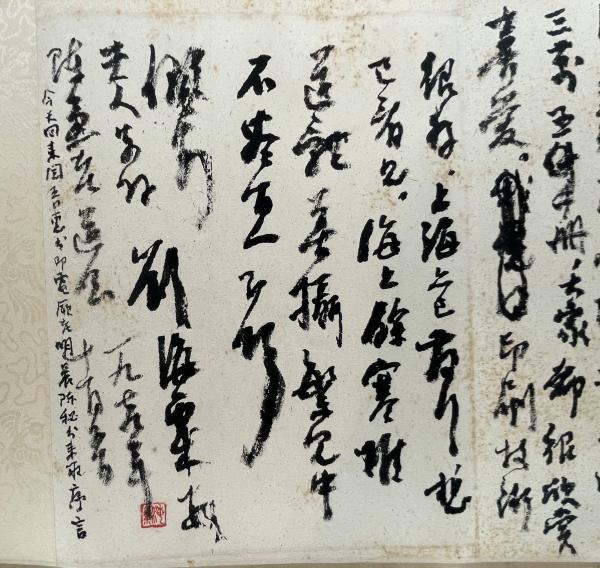

In the letters that Mr. Haisu sent to his family and friends at that time, he might have been worried about the country and the people, or thinking about a meal and a drink, or trivial matters of family life. He had no intention of writing, but he could be said to have aged both physically and mentally, and his writings were full of his own freehand style, vigorous and powerful. Reading them was like reading Lu Gong's "Sacrificial To My Nephew" and "Dispute over a Seat". For example, his letters to his wife Xia Yichao in 1976 and 1977, his family letters to Liu Yinglun in 1977, his family letters to Liu Qiu in 1977, and his letters to Li Baosen, Jiang Xinmei, Zhu Fukan, and Li Luogong in 1977 are all masterpieces of his representative calligraphy works, and they occupy a place in the entire history of Chinese literati calligraphy.

The experiences and sufferings of Mr. Liu Haisu in his later years were the "quenching" of life. It can be said that without those sufferings and long-term silence, there would probably not have been the brilliance of his later landscape paintings with splashes of ink and color, let alone such a style of wild, majestic and heavy calligraphy. The realm reached by Mr. Liu Haisu's letters in his later years and his paintings are the inside and outside of each other, and reading them can move people. The loneliness, indignation, transcendence and emotions expressed in them cannot be described in a few words.

This experience, on the one hand, reminds us of Dongpo's transformation during his stay in Huangzhou, and on the other hand, it reminds us of the famous works of all dynasties recorded in Sima Qian's "Letter to Ren An", most of which were "written out of anger. These people all have something in their minds that they cannot express, so they recount past events and think about the future. They are like Zuo Qiuming who is blind and Sun Tzu who has a broken foot. They are ultimately useless, so they retreat to discuss books and strategies to vent their anger and express themselves through empty writing."

Liu Haisu's Notes in His Later Years

(one)

When examining Su Dongpo's influence on Liu Haisu, it is related to his hometown Changzhou, his family, and his nature and character.

Su Dongpo's life was full of ups and downs. After leaving Sichuan, his footprints covered the whole country. He wandered for half his life, was sometimes appointed as an official, and sometimes was constantly demoted. The farthest he went was to the desolate Danzhou, Hainan. It is said that "his heart is like an ashes tree, and his body is like an untied boat. When asked about your life's achievements, they were Huangzhou, Huizhou, and Danzhou." All of these were passively caused by external forces. Only buying land in Yangxian, Changzhou, and returning to Changzhou in the north were his subjective choices. The famous line Su Shi left for Changzhou, "Thank you for the dim lamp that does not mind my guests, and for letting us stay together in the lonely boat for one night," is still engraved on the wall of the Dongpo Memorial Hall in Changzhou.

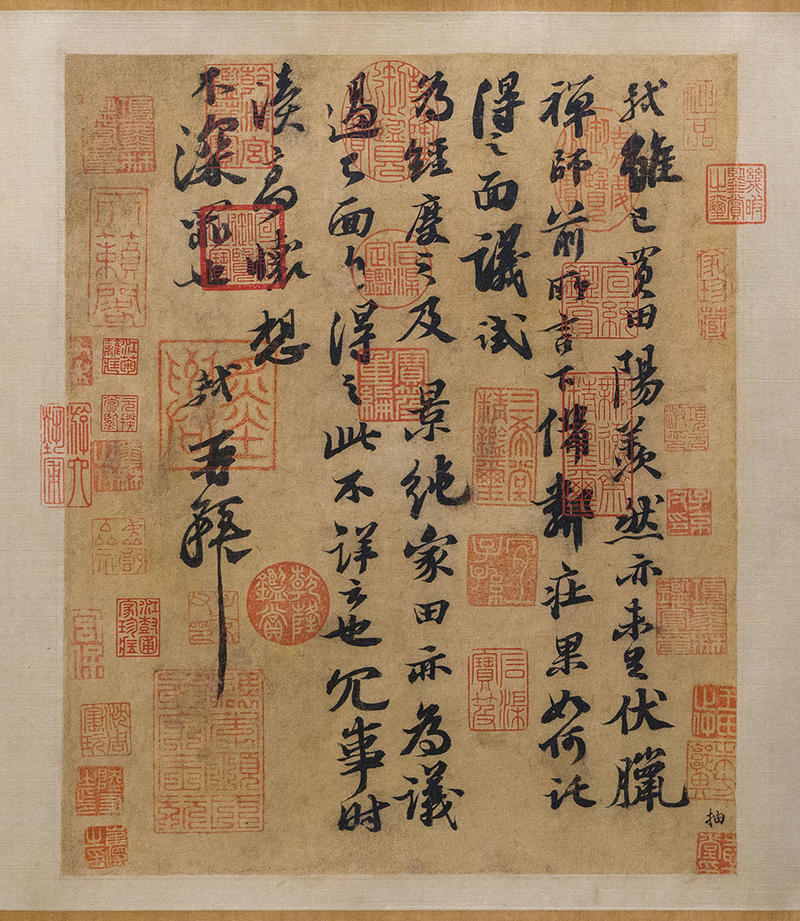

Su Shi's "Yangxian Tie" is collected by Lushun Museum. Interpretation: Shibsp; Interpretation: Although Shi has bought land in Yangxian, it is still not enough for the New Year. As the Zen master said before, about the preparations for the neighboring village, how is it really going? I will ask him to discuss it in person and try to make a rough estimate for me. Jingchun's family land was also discussed, and it has been made clear, but it is not clear how this was obtained. When busy with trivial matters, one neglects his lofty aspirations and does not think deeply about the sin. Shi bowed again.

In the fourth year of Xining (1071), Su Shi first encountered Changzhou on his way to Hangzhou. In mid-June of the first year of Jianzhong Jingguo in the Northern Song Dynasty (1101), Su Shi was pardoned from Danzhou and went north. He lived in Sun's Pavilion on the north bank of Gutang Creek in Changzhou and died of illness. He came to Changzhou more than ten times and left behind a large number of relics, cultural relics and poems, which can be seen in the old pavilion of wisteria flowers, the inkstone washing pool, the "Su Family Begonia" and the boating pavilion.

Su Che's "Epitaph of Mr. Dongpo" records: "In the seventh month of autumn, he fell ill and died in Piling. The people of Wu and Yue cried together in the market, and the gentlemen paid their respects at home. The news spread to all directions, and everyone, regardless of whether they were wise or foolish, wept. Hundreds of scholars from the Imperial College came together to give a feast to the monk Huilin at the Buddhist temple. Alas, culture has fallen! Where can future generations look up to it?"

The people of Wu and Yue mourned for the loss of a great culture, and their deep love was evident. In order to commemorate Dongpo, the people of Changzhou in the Southern Song Dynasty built a mooring pavilion to express their remembrance. Dongpo had a profound influence on the local culture of Changzhou after the Song Dynasty.

The relics of Su Dongpo in Changzhou have been chanted and remembered by literati of all dynasties in Changzhou.

In the Qing Dynasty, the historian Zhao Yi originally lived in Daixi Bridge in Wujin, and later moved to the front and back north bank (Baiyun Creek). His poems include: "I moved to the city for no reason, and I envied Su Dongpo's residence in Gutang", "I am ashamed that I don't have a seat as full as the Beihai Palace, but I am fortunate to have Su Dongpo's house as a neighbor". Hong Liangji, a writer and historian in the Qianlong and Jiaqing periods of the Qing Dynasty who was known for his outspokenness, recorded this: "Beside the Gutang Bridge on the north bank is where Su Wenzhong, the Duke of Song, played the zither. When I was a child, I would linger in this building every time I passed by it and could not bear to leave." Regarding Dongpo's inkstone pool, Hong Liangji wrote a poem: "The purple wisteria flowers bloom and the ink pool rises. Don't resist the colorful ancient colors"...

Changzhou Dongpo Inkstone Washing Pool

It is quite interesting that Hong Liangji was exiled to Xinjiang for his words. He wrote to the military minister Yongyan to express his opinions on current issues, which angered Jiaqing. He was imprisoned and sentenced to death. Later, he was exiled to Yili, Xinjiang. These hardships were a major blow to his political career, but they made him a literary peak. "I walked alone for thousands of miles, without seeing anyone. I passed through the Tianshan Mountains and waded through the vast ocean. I heard and saw wonderful things that I had never seen in my life. So I occasionally picked up my pen, but I wanted to describe mountains and rivers, and I would never dare to mention other things." His Yili Miscellaneous Poems, "Tianshan Hakka Talk", "Yili Diary", etc., either recorded the majestic scenery, or wrote about the peculiar folk customs, or described the beauty of the scenery. As the Qing Dynasty poet Zhang Weiping said: "Before you arrived (Xinjiang), your poems about famous mountains and scenic spots were mostly strange and warning... After traveling thousands of miles with a spear, you have experienced strange dangers and are full of strange spirits. It is true that mountains and rivers can help people."

Liu Haisu's great-grandfather, Qing Dynasty scholar Hong Liangji (1746-1809)

This is very similar to the situation where Su Dongpo was demoted to Huangzhou because of the Wudai Poetry Case.

In his Beijiang Poetry Talk, Hong Liangji emphasized "temperament" and "style" in his discussion of poetry, and believed that poetry should "have a unique style and express one's own temperament", which is consistent with Su Dongpo's theory of tone. Hong Liangji's Juanshige also had a collection of Shou Su Hui, which shows his deep admiration for Su Dongpo.

——And Hong Liangji’s granddaughter Hong Shuyi is Liu Haisu’s mother Hong Shuyi.

Mr. Haisu's daughter Liu Chan once told the author in a conversation during the Liu Haisu Calligraphy Exhibition in Shanghai that before her father passed away, she recalled that when she was a child in Haisu, her grandmother Hong Shuyi often told him stories, stories about Sima Qian and Su Dongpo, who did not care about adversity, were detached and open-minded, and the more difficult and difficult the situation was, the more motivated they were.

Mr. Haisu's memoirs include: "My mother, Hong Shuyi, is the granddaughter of the writer Hong Liangji. She was my enlightenment teacher in literature and art. In summer, she let me sit on her lap; in winter nights, she sat in bed, holding me in her arms, letting her warm heart touch my back, and taught me to recite ancient poems one by one. Until she passed away, I could not fully understand these poems, but I just thought they were nice and interesting, and I remembered them without any effort. When I was a child, the two writers my mother talked about the most were Mr. Hong Beijiang and his close friend Huang Zhongze. When talking about their unswerving love, She was very affectionate and was extremely proud of her grandfather's thousands of miles trip to the funeral of Huang Jingren. She often said: "A scholar must first have character and knowledge before he can be literary. Character and knowledge include moral character, knowledge and cultivation. There are those who are not of good character but have high art, such as Yang Su and Liu Yu who are good at poetry, Cai Jing and Yan Song who are good at calligraphy, Qian Muzhai who is good at both poetry and prose, and his annotations on Du Fu's poems with extraordinary insights. In the end, they were burdened by their character and were looked down upon by the literati and despised by others. If a person is not useful to others, he is still dead. A scholar who does not farm for food, does not weave for clothes, forgets the nourishment of our people, and is proud of his ability to serve the ministers, his literature and art must be worth watching. Will you work hard? ! '"

Another person worth noting is his uncle, modern scholar and historian Mr. Tu Jingshan, who was chivalrous and righteous by nature. He admired Sima Qian, Dongpo, Yun Nantian and other predecessors. He often took the childhood Liu Haisu to Dongpo's ruins and Tenghua Old House to tell the stories of Dongpo and Changzhou, interpret the Red Cliff Fu before and after, and comment on the life and articles of Sima Qian, Dongpo and others. Mr. Haisu also recorded in the article "Mr. Tu Jingshan", such as "My uncle admired Sima Qian the most in his life. He was generous and chivalrous, his writing was unadorned, and he kept his promises. Whenever he was half drunk, he would recite "Reply to Ren Shaoqing" aloud, and the window glass would buzz and echo. Whenever he talked about the gains and losses of political affairs and the suffering of the people, he would sometimes slap the table, sometimes sigh, and his eyes would be crystal clear. Tears came from the bottom of his heart and he couldn't help himself."

It can be said that the dual influence of local literature and history and family education made Su Dongpo's spiritual personality grow in the deepest part of the young Liu Haisu's heart: both Sima Qian and Su Dongpo had a lifelong influence on Liu Haisu, especially his bold and unrestrained personality, his tenacity and fortitude, his broad-mindedness and clarity, as well as his "a belly full of inappropriateness".

(two)

What is the significance of Dongpo? Qin Guan, a disciple of Su Shi, said: "Su Shi's teachings are most profound in the state of self-satisfaction with one's nature and life." The so-called self-satisfaction with one's nature and life refers to a kind of great freedom that transcends utilitarianism and the pursuit of life, or it can be said to be the great freedom of letting nature take its course.

Su Dongpo was a man of utmost sincerity and temperament. Reading his works is like reading Zhuangzi: "I had insights in the past, but could not express them in words. Now that I have read Zhuangzi, I have felt it!" A sense of the vastness of life and temperament and great freedom runs through to this day.

Due to the times, there are of course huge differences between Liu Haisu and Su Dongpo. Su Dongpo's unrestrained and open-minded character shows his simplicity, while Haisu's eccentric character shows his sincerity. Su Dongpo's influence on Liu Haisu lies first in his pursuit of the utmost sincerity and nature of his personality and the pursuit of great freedom in life.

Liu Haisu once said in "Art and Life Confession" published in "Shishi Xinbao|Xue Deng" in September 1924: "The true meaning of life should also be to live naturally and return to human innocence, which will naturally be full of interest, not bound by material and interests, without any calculation or scrutiny, and without good or bad, good or evil... Art is emotional, and the confession of painting is to give full play to emotions."

Reading these words, it seems as if they came from Su Dongpo. Besides letting nature take its course, the so-called "art is the expression of emotion" is actually about writing about emotions and thoughts, which is in line with Su Dongpo's theory of freehand painting.

The so-called "utmost sincerity and nature" or "a life of letting nature take its course" is actually just an ideal. In real society, it is bound to be beaten to a pulp, just as Su Dongpo said, "a belly full of inappropriate things."

Mr. Haisu particularly loved Su Dongpo's line "When he puts pen to paper the wind and rain are swift, the energy is already swallowed before the pen reaches it." He wrote this line many times. Looking at his paintings and calligraphy in his later years, we can see that they are all full of heroic spirit and he wrote very quickly. In a letter to a friend, he mentioned Mr. Zhou Qingding, saying that the two were similar in that they "focused on qi" and that he "wrote qi rather than form." In another letter to Mr. Zhu Fukan, he mentioned the difficulties he faced in writing lyrics and in the 1960s, such as house confiscations and expulsions. The letter said that he was "fearless and unyielding." In contrast, I heard Xie Gongchunyan say that when he faced a criticism and denunciation meeting during the catastrophe of the Cultural Revolution, he saw the sea of heads below and actually imagined that it was the "sea of clouds at Huangshan." This was the darkest moment of his life, he was wandering in the sky, contented, and really got the essence of Su Dongpo's "a grain of sand in the vast ocean."

(three)

The handwriting reflects the heart. For example, Su Dongpo's calligraphy was influenced by the "Two Wangs" in his early years, and he liked Yan Zhenqing and Yang Ningshi after middle age. In his later years, he also learned Li Beihai. Huang Shangu said: "Su Dongpo Taoist learned the Lanting when he was young, so his calligraphy is graceful like Xu Ji. When he was drunk and unrestrained, he forgot about the skill and clumsiness, and his characters were thin and strong, like Liu Cheng. In his middle age, he liked to learn the calligraphy of Yan Lugong and Yang Fengzi, and his combination is no less than Li Beihai. As for the roundness of the strokes and the rhythm, his articles are wonderful in the world, and his spirit of loyalty and righteousness runs through the sun. He should be ranked first among the calligraphers of this dynasty."

In his postscript to Su Dongpo's "Ren Lai De Shu Tie", Dong Qichang quoted Du Fu's poem to praise Su Dongpo's calligraphy: "In a moment, the nine-fold true dragon emerges, washing away all the ordinary horses of the ages". In "Painting Zen Room Essays: On the Use of Brush", he said: "Suddenly, Su Dongpo's calligraphy is heavy. Mi Xiangyang called it painting words, which means that he writes freely." This reminds people of the famous sentence in Su Dongpo's composition: "Like flowing clouds and running water, it flows where it should flow and stops where it must stop". The grammar is the same as calligraphy, that is, the brush is natural and free, showing the state of life and emotional expression, and the emphasis is on writing "intention", and expressing emotions in the dots and strokes written "freely", that is, "my writing is created by intention" and "I have no intention of being good."

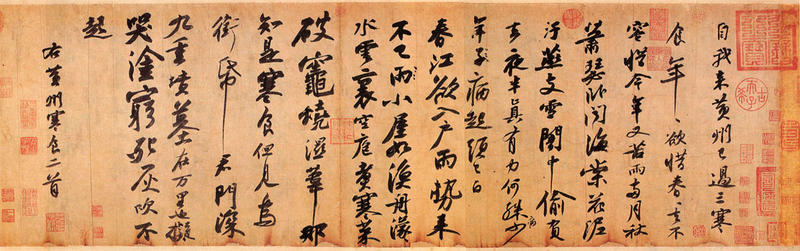

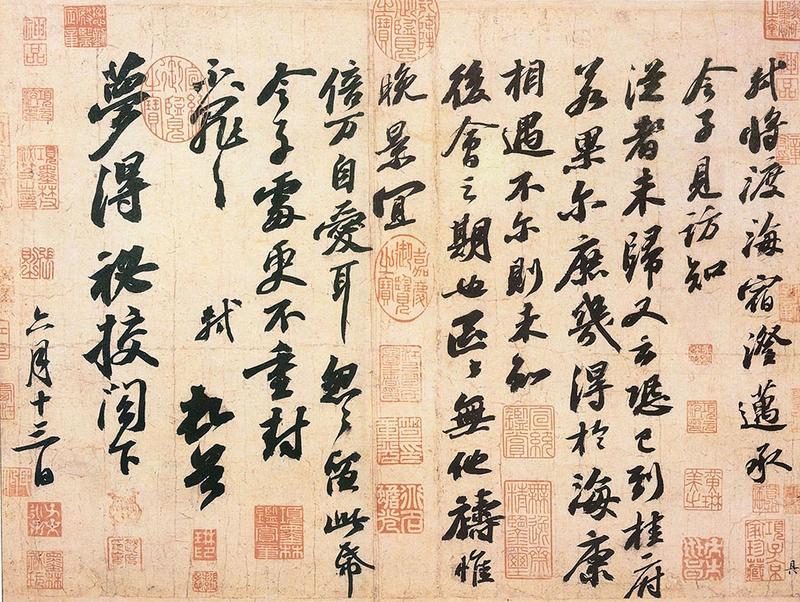

Su Dongpo's calligraphy mostly uses a sideward stroke, which is natural and vivid, with a flat and slightly fat structure, showing a sense of clumsiness. The "Huangzhou Cold Food Poetry Post" from his mature period of calligraphy style can particularly be seen in his emotional changes and freehand style. This poem of dissipation is a sigh about life expressed by Su Shi on the Cold Food Festival in the third year after he was exiled to Huangzhou. The poem is written in a desolate and melancholy tone, with a small house, an empty kitchen, cold vegetables, a broken stove, wet reeds, and a grave... Under such gloomy and sad imagery, the calligraphy was also written in this mood and situation, and the changes in mood and emotions are embodied in the changes of dots and lines, either straight or side, with various transitions, and they are connected smoothly and naturally. With the changes in mood, the characters are either large or small, sparse or dense, and they are scattered and scattered, just like nature. In particular, we can see the ups and downs of Su Shi's emotions and the sadness of his life.

Su Dongpo's "Huangzhou Cold Food Poems"

Among the early calligraphy works of Liu Haisu that can be seen at present, there are two inscriptions he wrote on photos of his father Liu Jiafeng's mourning hall in September 1919. He was 24 years old that year. His calligraphy skills can be seen. His strokes are fluent and free, and the characters are a blend of Yan and Liu, showing thick and plump characters. The influence of Su's characters can also be vaguely seen, especially in the characters such as "Big brother, who knows", which have a flat structure and a sideways posture, which is almost a typical style of Su Dongpo's calligraphy. Against the background of his family education, it can be said that it was inevitable that he practiced Su Dongpo's calligraphy and was influenced by him.

Liu Haisu's early calligraphy, 1919

In 1921, 26-year-old Liu Haisu was accepted as a disciple by Kang Youwei. Kang admired inscriptions, so Liu Haisu turned from calligraphy to epigraphy, and copied various inscriptions on bronze and stone inscriptions many times, including "Sanpan", "Shigu", "Shimen Inscription", "Zheng Wengong Stele", etc. He also learned Kang's style of calligraphy very vividly, which can be seen in his calligraphy works in 1923 and 1924.

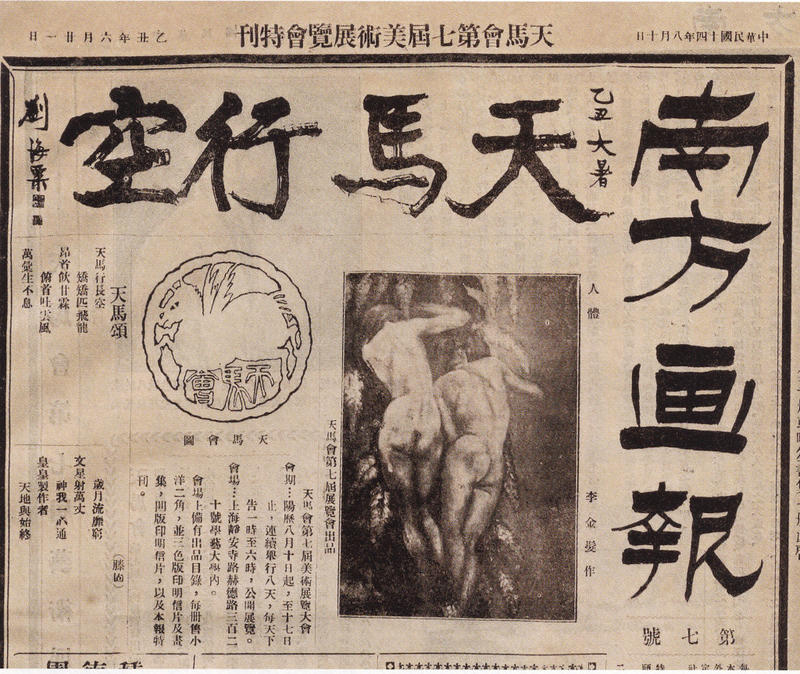

Liu Haisu's "Unrestrained Thoughts" in Kang Youwei's style, published in the Republic of China Pictorial

Interestingly, in 1925, four years after he became Kang's disciple, Liu Haisu, who was in his thirties, still wrote in Kang's style when he wrote inscriptions and paintings. However, a letter to Li Gufan that can be seen now is completely in the style of calligraphy, with the brushwork flowing smoothly, "My dear brother Gufan, it's been a long time since we last met. I miss you so much... Where is your residence in Shanghai after you came? This is written in a hasty manner." Perhaps there is no need to be pretentious when writing letters to friends. After all, he should show his true colors. He has no intention of writing, but instead shows the profound influence of Lu Gong and Dongpo's handwriting on him. The "Gong'an" at the end of the letter and the signature "Liu Haisu" are particularly elegant and powerful.

In his later years, he said in his article "Remembering Mr. Kang Youwei":

"I learned Kang style calligraphy and was quite good at it. After 1927, I started practicing the Sanshi Pan Inscription and also studied the cursive scripts of Zhang Xu and Huaisu for a while. Therefore, although I retained some of Mr. Kang's style in terms of the strokes, I changed it and began to pursue my own artistic personality, gradually breaking away from the confines of Kang style."

Liu Haisu's calligraphy after 1927 is more of an integration of inscriptions on the stele and has the simplicity of Wei tomb inscriptions. However, if one looks closely, whether it is "Letter to Bo Weng" in 1932, or the inscription "Haisu Masterpiece" in 1933, or the inscription on "The Solitary Pine in Huangshan" in 1935, one can see the slanting tendency of the brush strokes, and the characters are flat, slanted and plump, simple and crude, with a sense of official script, and one can also vaguely see the style of Su Dongpo and other Song dynasty calligraphers.

The earliest copy of Su Dongpo's calligraphy that can be seen at present is the four-panel copy of Su Dongpo's "Huangzhou Cold Food Post" in 1942, which was enlarged and copied. It was during the Anti-Japanese War when Liu Haisu went to Southeast Asia to raise funds. He was trapped in Indonesia and practiced calligraphy every day. In the morning, he copied Su Dongpo's "Cold Food Post" and in the afternoon, he copied Huang Tingjian's "Songfengge Post". Before and after this period, he also copied the calligraphy of Ming Dynasty calligraphers such as Wen Huiming. In comparison, although the copy of Su Dongpo's "Huangzhou Cold Food Post" also tries to follow Su Dongpo's calligraphy, and the shape is also flat and slanted, but it shows more thinness, and the inherent plumpness of Su Dongpo's "house" and "that" is also weakened.

Liu Haisu's imitation of Su Dongpo's "Huangzhou Cold Food Post" in 1942

However, the influence of Su Dongpo's and Han Shi Tie's calligraphy styles for a long time on Liu Haisu's calligraphy was almost deep-rooted. Especially when he was facing setbacks in the world, it was almost inevitable for him to draw spiritual strength from Su Dongpo's poems, essays, and paintings.

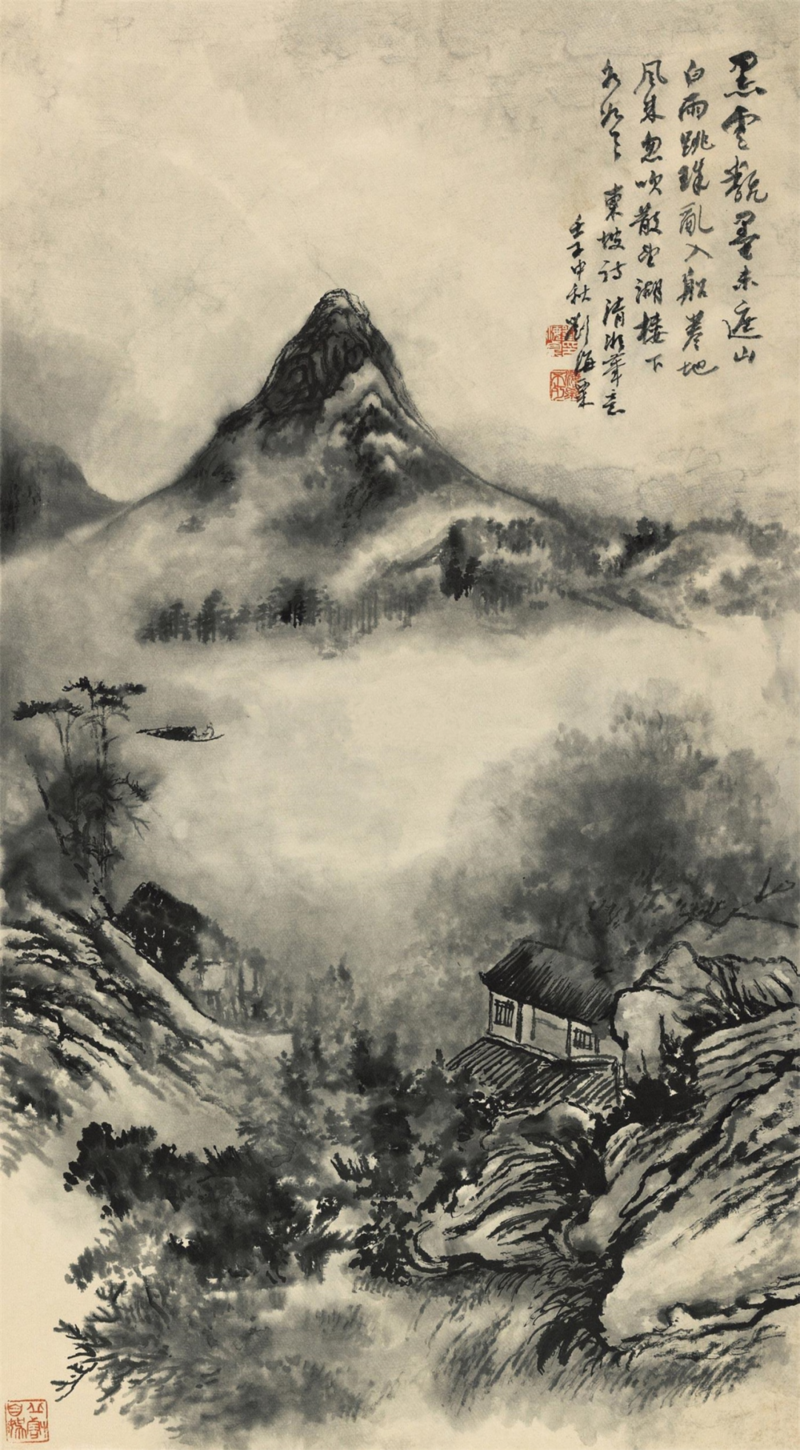

In 1972, he presented the British cultural scholar Jingru with a painting titled "Su Dongpo Poetry". It was written in the style of Qingxiang, with the inscription: "Black clouds are like ink but have not covered the mountains, white raindrops are like pearls and randomly fall into the boat. The wind blows and suddenly blows away, and the water under the Wanghu Tower is like the sky. Su Dongpo's poems, written in the style of Qingxiang. Mid-Autumn Festival of Renzi (1972), Liu Haisu."

Liu Haisu's landscape painting "Poetic Picture of Dongpo"

The poem "Bodhisattva Man" presented to Huang Baofang in 1970 blends running script with regular script and is written with meticulous brushwork. Words like "chao" and "zhu" are flat and have a touch of Su Dongpo's style.

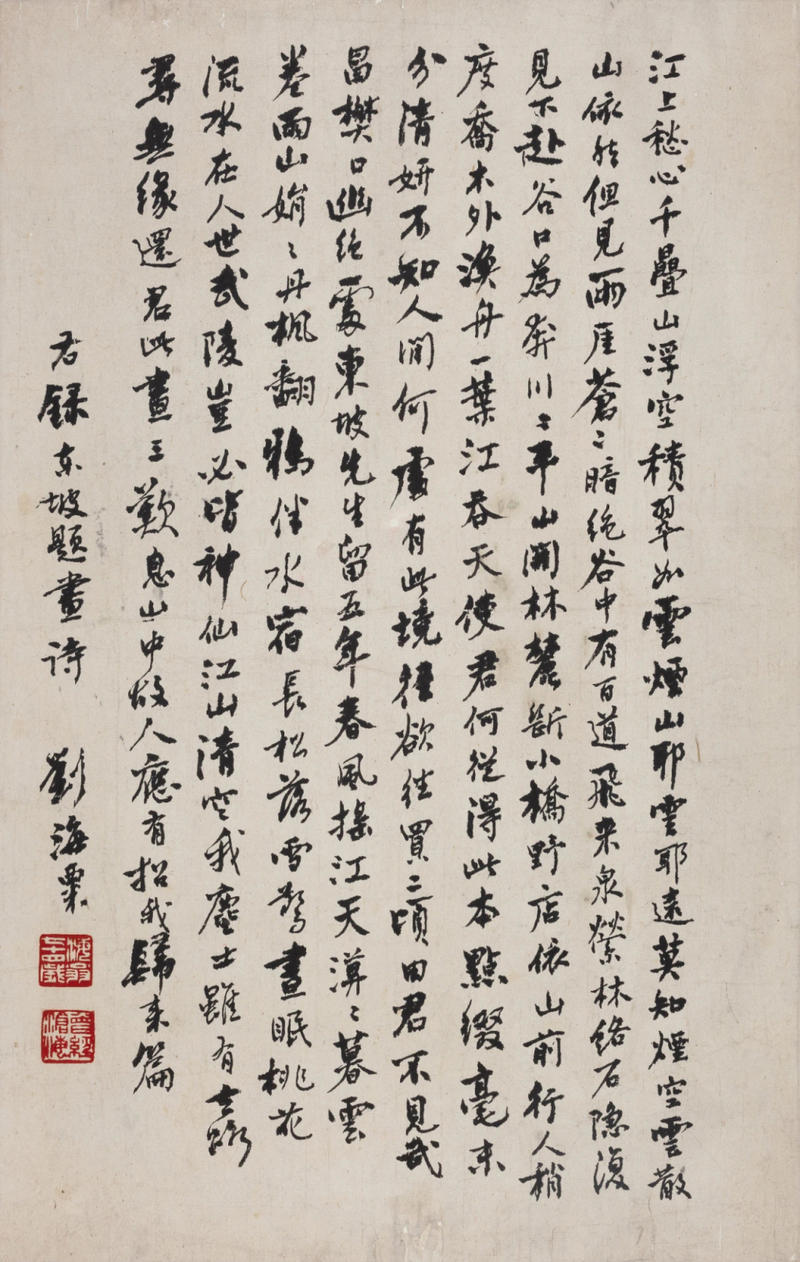

"Records of Su Dongpo's Poems on Paintings" (undated, but probably written around 1970 based on the style of calligraphy): "A thousand mountains of sorrow are stacked on the river, and the floating green in the sky is like clouds and smoke. Whether they are mountains or clouds is too far away to know, the smoke and clouds disperse but the mountains remain...A fishing boat is just a leaf on the river swallowing the sky. How did you get this copy, to embellish it with every detail to make it clear and beautiful. I don't know where in the world there is such a place, so I want to go and buy two hectares of land. Don't you see the secluded and remote place in Fankou, Wuchang, where Mr. Su Dongpo stayed for five years...My old friend in the mountains should have a poem to invite me back." This book is simply an homage by the elderly Liu Haisu to Su Dongpo's "Cold Food Poems" and "Red Cliff". The words "a fishing boat" and "return" all reveal a strong Su flavor.

Liu Haisu recorded Su Dongpo's poems on paintings in his later years

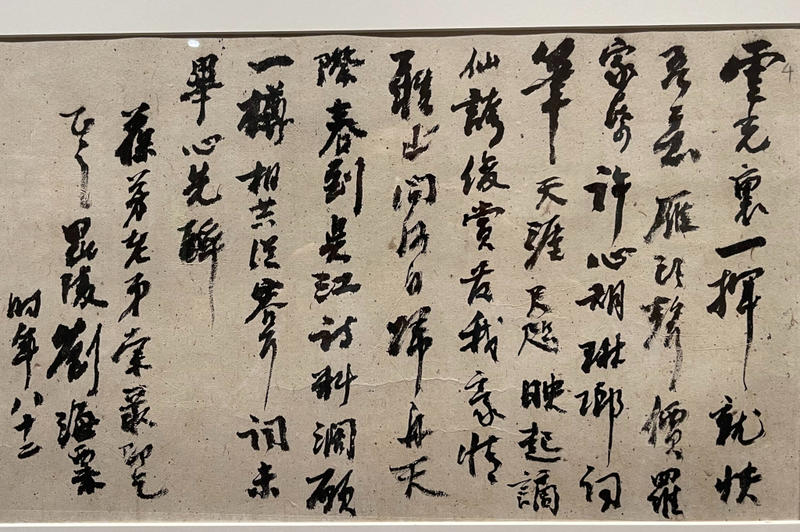

Even in his representative letter "Letter to Huang Baofang", which was his mature calligraphy period when he was 82 years old in 1977, the "wind god" and "thousand years" in his "Jinlou Qu" and the "(teng jue) in the cloud light" in "He Xinlang", his brushwork and writing style are exactly the same as the "(meng meng) in the water and clouds" in Su Dongpo's "Cold Food Poetry Post", the elongation of the last stroke of "hui" in "one stroke" and the elongation of "year" in "year after year".

Letter to Huang Baofang

(Four)

Liu Haisu's calligraphy progressed from calligraphy to stele in his twenties, and from stele to calligraphy in his forties and fifties. In the 1960s and 1970s, when he was at the lowest point in his life, he went from calligraphy to stele, and then back to calligraphy again. The richness, complexity, tension, and vigor of the brush and ink are different from those of his predecessors. However, if we examine the sources of his achievements in handwriting calligraphy, we have to say that the influence of Yan Lugong and Su Dongpo's manuscripts on him is the influence of his sincerity and naturalness, his unintentional attitude towards calligraphy, the so-called "unintentional calligraphy is good", especially in his letters around 1975, in which he put aside all the techniques of dotting and strokes, as if Lugong was fighting for a seat and falling down, with his mind and hands forgotten, and he wrote about his temperament, which is consistent with Su Dongpo's "My writing is created by my own ideas, there is no rule", with ideas as the main focus and his brush moving freely, thus truly creating the true peak of Liu Haisu's calligraphy.

This can perhaps be said to be the result of the hardships brought about by the ten-year catastrophe. It is true that blessing and misfortune may come together, and misfortune may also bring blessing and misfortune.

Mr. Haisu's calligraphy truly matured and transformed after 1975, which could be called the "transformation at the darkest moment": around 1957, he was labeled a rightist for his outspokenness, and later suffered a stroke. His recovery was short-lived, and in 1966, when the movement began, his home was searched, he was criticized and denounced, and he was forcibly "swept out" and moved out of his original home. After moving to Ruijin Road, he had fewer social engagements and instead became more immersed in his own heart.

In this regard, Liu Chan recorded in a conversation with the author: "During that period, my house was sealed off, leaving only a living room, where my father, mother and a few of us slept on the floor. The only furniture was a square table and four chairs, and the family had only 20 yuan for living expenses. Except for my father who had a bottle of milk, we had vegetables and hot sauce for three meals a day. After that, we were kicked out of the house again, and the whole family moved to another small place. But my parents never sighed, they were very optimistic and joked with each other. Although the family lived a hard life, they were very happy. As long as he could paint, my father was happy. He said: An old horse in the stable still has a thousand miles to go. He didn't believe that the current situation would last long."

"Fortunately, a male worker was kind-hearted and knew that Dad loved painting. Before moving, he took some brushes, inkstones, paper and painting albums from the old house while the Red Guards were out, and secretly sent them to Ruijin Road by stuffing them in his clothes." "Dad finally lived a peaceful life. His student found an old seven-light table lamp at a flea market on Huating Road. Dad was so excited that he picked up the brush again."

It can be said that the great value of these letters lies in the fact that they inherit the straightforwardness from Yan Lugong and Su Dongpo, that is, to use sincere emotions to control the writing, and to write freely and unrestrainedly under the outpouring of emotions, regardless of the skill or clumsiness. Those letters were the voices of extreme sorrow and indignation caused by the catastrophe, and the expression of emotions in a state of "forgetfulness". It can be said that they were not writing, but expressing the sorrow and indignation in their hearts.

During his illness in the 1960s and the 1970s, he experienced great changes in his life and reread the inscriptions on bronze vessels. His calligraphy style gradually began to merge with steles and calligraphy, and became vast and thick. However, his calligraphy still had many lingering flavors of calligraphy. Although the vastness of bronze inscriptions had gradually been incorporated into his style, it had not yet reached maturity. In 1975, on the occasion of his 80th birthday, Liu Haisu wrote two copies of "Inscriptions on the Sanshi Pan", one for a friend and one for himself. The postscript reads: "Learning calligraphy must start with seal script. I have recently been copying the Maogong Ding and am fond of studying the Sanshi Pan. This year I am turning 80, and I am copying the Sanshi Pan again to celebrate my birthday. As I am old, the words are winding all over the paper, and I am still a bit lazy."

Postscript to Liu Haisu's Linsanshi Pan Inscription

By repeatedly copying inscriptions on the Sanshi Pan and other inscriptions, he borrowed from that kind of strange, vivid, simple and unrestrained font, and integrated it into his brushstrokes, transforming his sixty or seventy years of calligraphy exploration. He was also influenced by the transcendent and open-minded style of his previous copy of Su Dongpo's "Cold Food Post" and other calligraphy works, so he injected the loneliness and indignation in his heart during the catastrophe into his cursive script with a winding brushstroke and a dry meaning, and finally achieved a true state of both man and calligraphy.

Su Shi's "Crossing the Sea Letter", running script, the third year of Yuanfu (1100), collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Letter from Liu Haisu in His Later Years to Liu Lun

Liu Haisu's Letter to Huang Baofang

Liu Haisu's Notes in His Later Years

First draft on the evening of January 13, 2025, Shanghai Sanliu Bookstore

(This article was originally published in the first issue of Shanghai Art Review in 2025)