During the Age of Exploration, European ships returned home from the distant East loaded with precious Chinese blue-and-white porcelain. When porcelain was introduced from China to Europe, the unique decorative style of "Chinoiserie" also emerged, carrying Europeans' fantasies about the East and their obsession with exotic cultures, embellishing the living spaces of countless European families. Recently, the special exhibition "The Beauty of Grotesque: Chinoiserie from a Female Perspective" at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York put "Chinoiserie" in a dialogue across history and the present, and explored the prevalence of ceramics in Europe from a female perspective.

Exhibition Hall Atrium

Ceramics, this elegant but fragile material, was once closely linked to women's aesthetics in history. Its fragile and sharp characteristics have become a metaphor for women's identity, giving them a leading role in desire, consumption and cultural narratives. The exhibition title "monstrous" was once used to describe porcelain, alluding to people's fear of the unknown. And it is precisely these indescribable and disturbing existences that are often full of mysterious attraction and tempting people.

Willem Kraft (Dutch, 1619-1693), 1659, oil on canvas

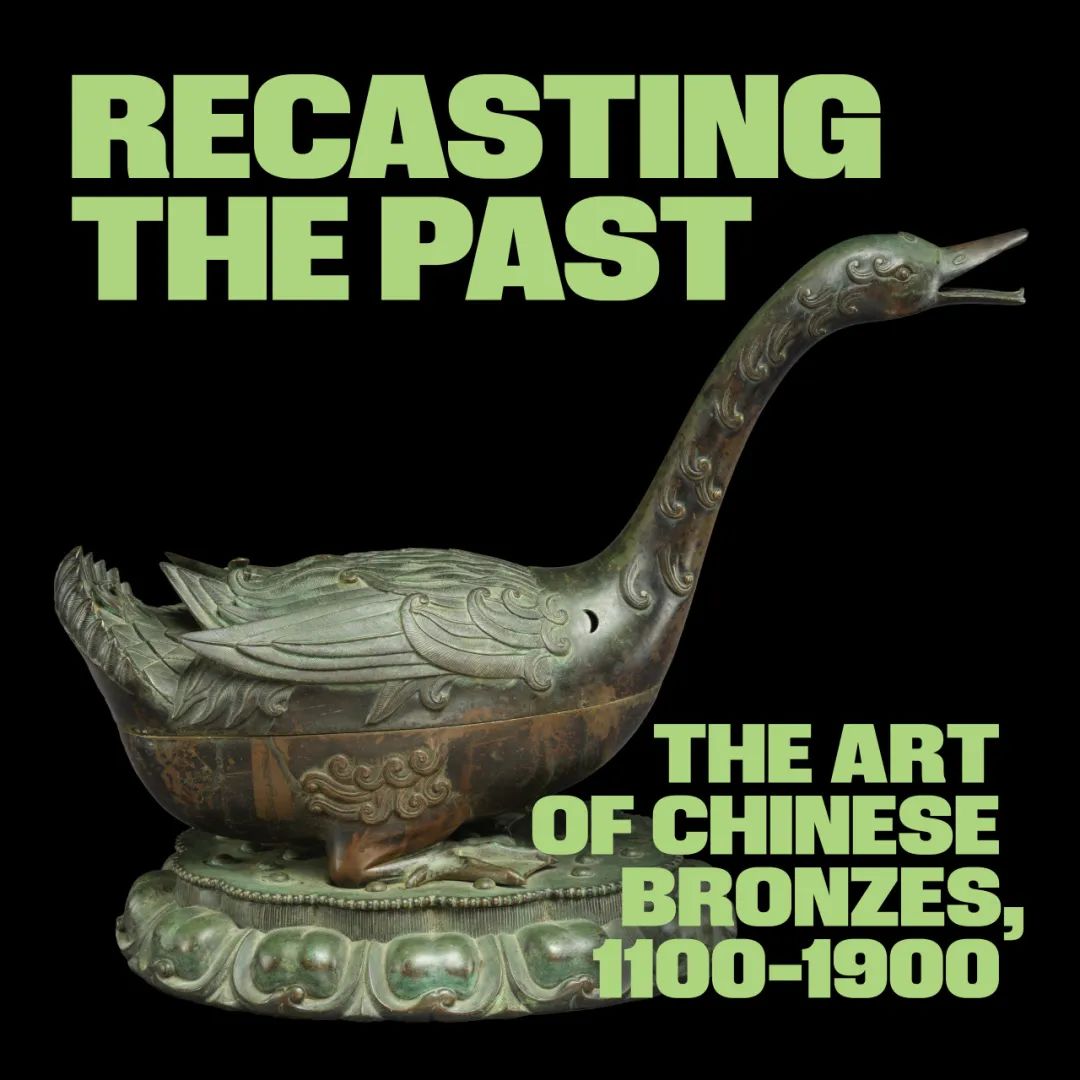

From European artifacts from the 16th century to installations by contemporary female artists such as Zhang Yi and Liu Huide, the exhibition "The Beauty of the Grotesque: Chinese Style from a Feminist Perspective" brings together nearly 200 historical and contemporary works, revealing that Chinese style is not a neutral, harmless exotic fantasy, but a complex cultural phenomenon. In addition, the exhibition will also explore how porcelain plays a role in the identity of European women, but how it deepens the racial and cultural stereotypes surrounding Asian women.

Shipwrecks and Sirens: When Porcelain Arrived in Europe

In the 16th century, when blue and white porcelain arrived in Europe across the ocean, it was regarded as a mysterious and wonderful foreign object. At first, merchants used these porcelains as ballast to stabilize ships and withstand rough seas. Until one day, they realized the commercial value of these porcelains.

Previous: Porcelain salvaged from the Dutch shipwreck "White Lion"

At first, the nobles regarded porcelain as a treasure, decorating and displaying it with gilded stands. By the end of the 17th century, shiploads of porcelain were circulating among the fiercely competitive trading powers such as Portugal, England and the Netherlands, and were auctioned at high prices.

Cup and saucer, China, early 18th century, hardwood porcelain

During these voyages and trades, the anxieties of shipwrecks, wars, and colonization, though never expressed directly, secretly emerged in the decorative patterns on porcelain. The image of the siren, both beautiful and deadly, appeared in painted teacups and carvings, just like the characteristics of porcelain itself: full of temptation, but elusive. Europeans tried to reveal the composition of porcelain, some said it came from "rotten feces for many years", while others said it came from crushed shells.

Made in the Medici Porcelain Workshop (Italy, circa 1575-1587), ewer, circa 1575-80, soft porcelain.

Porcelain is both a rare object of desire and a source of derogatory language and prejudice. The name “porcelain” comes from the Venetian slang “porcellana”, meaning “little pig”, which was originally used to describe the narrow slit of the shell of the porcellus, which was believed to resemble the private parts of a pig. Ironically, this shell was later used as currency by European merchants to trade and enslave African people.

The double: Marie II's obsession with porcelain

At the end of the 17th century, Queen Mary II of England developed a deep obsession with the "Chinese style". This obsession not only shaped her personal aesthetic, but also sowed seeds and spread in the hearts of generations of European female collectors.

Studio of Adrianus Cox (Netherlands, 1689-94), Tile with upper bust of William III, c. 1694, Delft ceramics.

Mary grew up in the Stuart dynasty, which was characterized by intense political and religious disputes. At a young age, she was forced to marry her distant cousin, William, Prince of Orange of the Netherlands, and moved to a foreign country. It was in the Netherlands that she encountered the world of exotic luxury. A few years later, her Protestant husband overthrew her Catholic father and ascended the throne of England, and Mary returned home with her beloved ceramic collection.

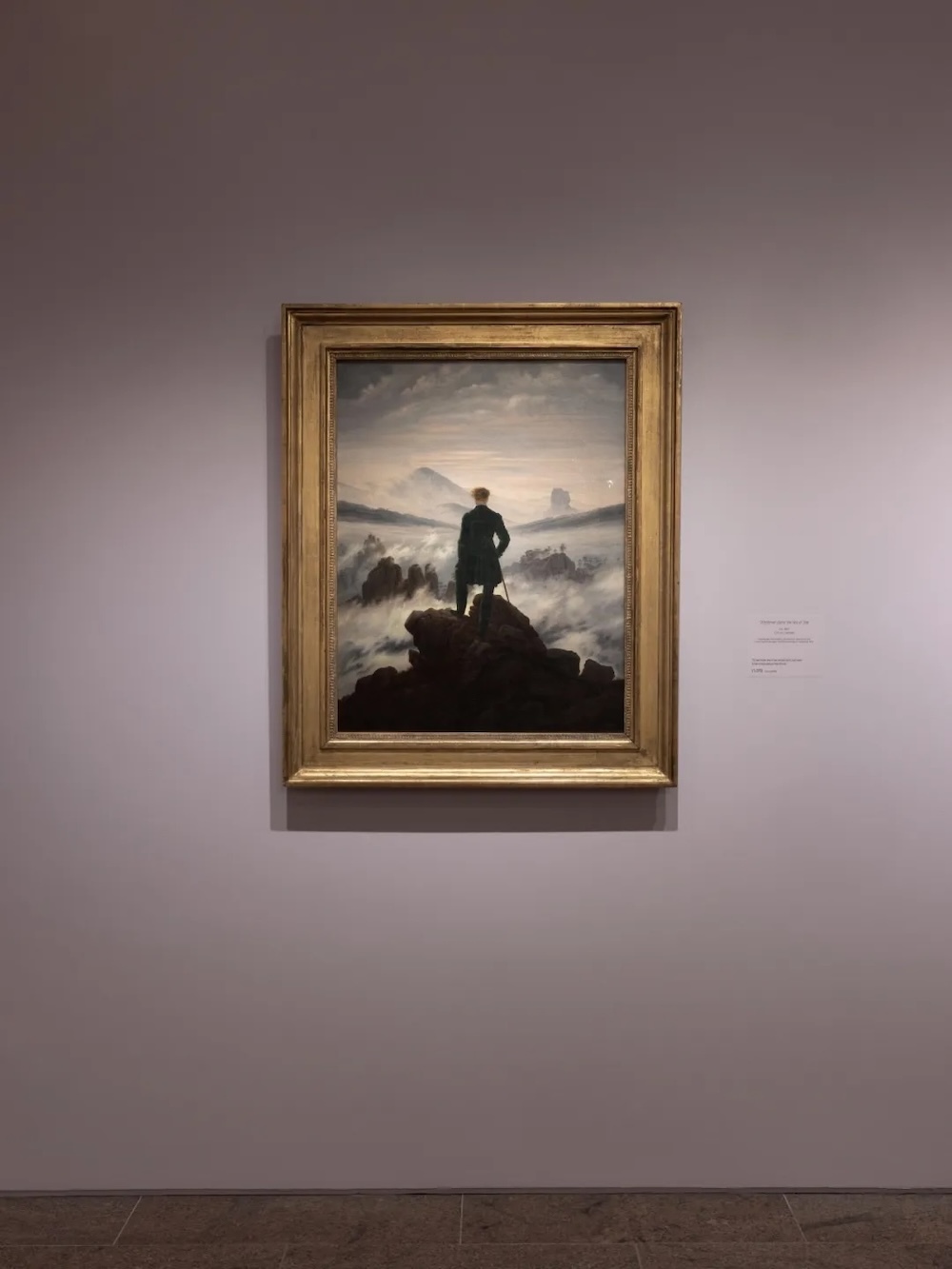

Tourists admiring the portrait of Queen Mary II at Through the Looking Glass

But even the Queen's body never belonged to her. Although she shared the throne with William, Mary's most important task was only one: to give birth to an heir. However, Mary never had children. So she gave birth to her own continuation in another way - she gave birth to a taste, a style. Porcelain became her stand-in, decorating her palace full of colored porcelain, brocade and lacquerware. Her interpretation of "Chinese style" was private and feminine, far different from the way the French royal family used exotic beauty to demonstrate absolute power.

Exhibition View

After Mary’s death, one prominent writer lamented that she had unleashed a “fatal spending frenzy” that would lead women to a frenzy of china purchases that would eventually lead to economic ruin. But few people heeded his warning.

Tea talk: daily family life

In 1662, Portuguese Princess Catherine of Braganza first arrived in England. She asked for a cup of hot tea from the greeter, but the greeter looked confused. Tea, this exotic drink from China, was still unfamiliar to them.

However, it wasn’t long before tea became a fashionable new favorite among the nobility. By the 18th century, it had become deeply rooted in everyday European life. Especially in England, tea was seen as a symbol of civilization and a tool for the empire to draw a clear line between itself and the “barbaric” lands it plundered. At the same time, stereotyped images of Africans and Chinese frequently appeared as decorative patterns on European tea sets. These “decorations” became an embellishment of luxury life, but also witnessed the real scars brought by colonial history.

Teaware exhibits of different styles

Porcelain gradually became a symbol of proper family order. On the dining table, women, in their roles as hostess, mother, wife, daughter, and even maid, skillfully arranged the utensils depicting oriental exotica. However, behind this daily routine, there was an undercurrent of unease - the family was like a cage and a lock.

Lin Congxin (USA), Tea Table, 2016, etching on Japanese mulberry paper.

The popularity of porcelain made women gradually rise to become consumers and tastemakers, gradually occupying a more important role in society, and also triggered social anxiety at the time. The "fragility" of porcelain is not just a physical property, it is also projected as a metaphor for uncontrolled female desire. Even the whispered gossip in a seemingly peaceful tea party is regarded as a destructive and dangerous behavior.

Some of the tea sets on display

Some of the tea sets on display

Some of the tea sets on display

Artificial Mothers: Porcelain Dolls and Women

In the 18th century, porcelain dolls of Asian women appeared in Europe, bringing with them a strange and complex world. This world includes goddesses, mothers, monsters, and performers on stage. Early European porcelain craftsmen imitated the images of Asian gods out of religious contexts. In the later period, these porcelain dolls gradually solidified into a set of standard types that could be reproduced, mostly from images in prints.

Prints of Asian women

Ceramic Crafts

Porcelain figurines dressed in gorgeous clothes and posing in exaggerated postures are randomly placed and displayed on shelves, beside dining tables, or in cabinets. Their bodies are made of an artificial material that should have been used to make plates, saucers, and teacups, which is in sharp contrast to the female nude statues that were praised and deified in the European classical tradition. These porcelain figurines have become both a projection of desire and an object of deification. Their existence has become one of the origins of the subsequent stereotype of Asian women.

Ceramic Crafts

In this area that is considered "artificial", another possibility of women quietly emerges: a weird, substandard image that is outside the scope of classical perfection.

These small, toy-like porcelain figurines, along with the painted mirrors for export during the same period, were originally luxury goods that catered to superficial interests and lacked any deep meaning. However, when we look at them again today, they seem to become a crack, leading to another time and space - where women's self-awareness and the projection and expectations of the outside world on them are intertwined and confronted with each other.

Exhibition Hall Scene

The lingering charm of "Chinese style"

The illusion of porcelain did not stop in Europe. In the United States in the 19th century, the new medium, like the popularity of porcelain in Europe, reflected the imaginary projection of "Oriental women", and porcelain also became a tool of national ambition at this time. Through the route across the Pacific, American merchants gained wealth from the trade of luxury goods such as porcelain. At the same time, their growing participation in the illegal opium trade also gradually tainted the so-called "Chinese style" with danger and sin. This transformation is exactly the same as the hostile attitude of American society towards Chinese workers at that time.

When Empress Dowager Cixi of the Qing Dynasty and Anna May Wong of Hollywood appeared in the public eye, the "Chinese style" had already been covered with a layer of nostalgia. These two women from different cultures and classes used themselves as a medium to make changes through the public, but they were also stared at and simplified as symbols of moral corruption. In that era, they were out of place and a microcosm of the dilemma of Asian women's image: there was only a fine line between fame and stigma.

The evening gown worn by Anna May Wong is on display at the exhibition

Porcelain is not always a gentle ceremonial object. It has also shaped some cultural stereotypes that are still difficult to shake. For this reason, this fascinating history must also become a necessary dismantling of old myths - myths about race, gender and desire. As a result, the exhibition raises a question that goes straight to the heart: Can we love the past without being trapped by nostalgia?

Today, in order to break these deep-rooted myths of "exoticism", while examining history, several contemporary female artists have responded with their art and challenged the old system with their actions. Their works are displayed in the exhibition hall with bright neon labels, turning the negative elements of "Chinese style" into a powerful new visual narrative.

The exhibition will run until August 17th.

lEOvVUgh qLoRmwb gUYVO zdSYepI lGEJslZw