Since its opening, the Shanghai Pudong Art Museum, located on the bank of the Huangpu River, has quickly become a hot topic in the city with queuing up to visit the exhibition. This is the third time that the collections of the Musee d'Orsay have been exhibited in Shanghai, and all three times have sparked a wave of exhibition enthusiasm.

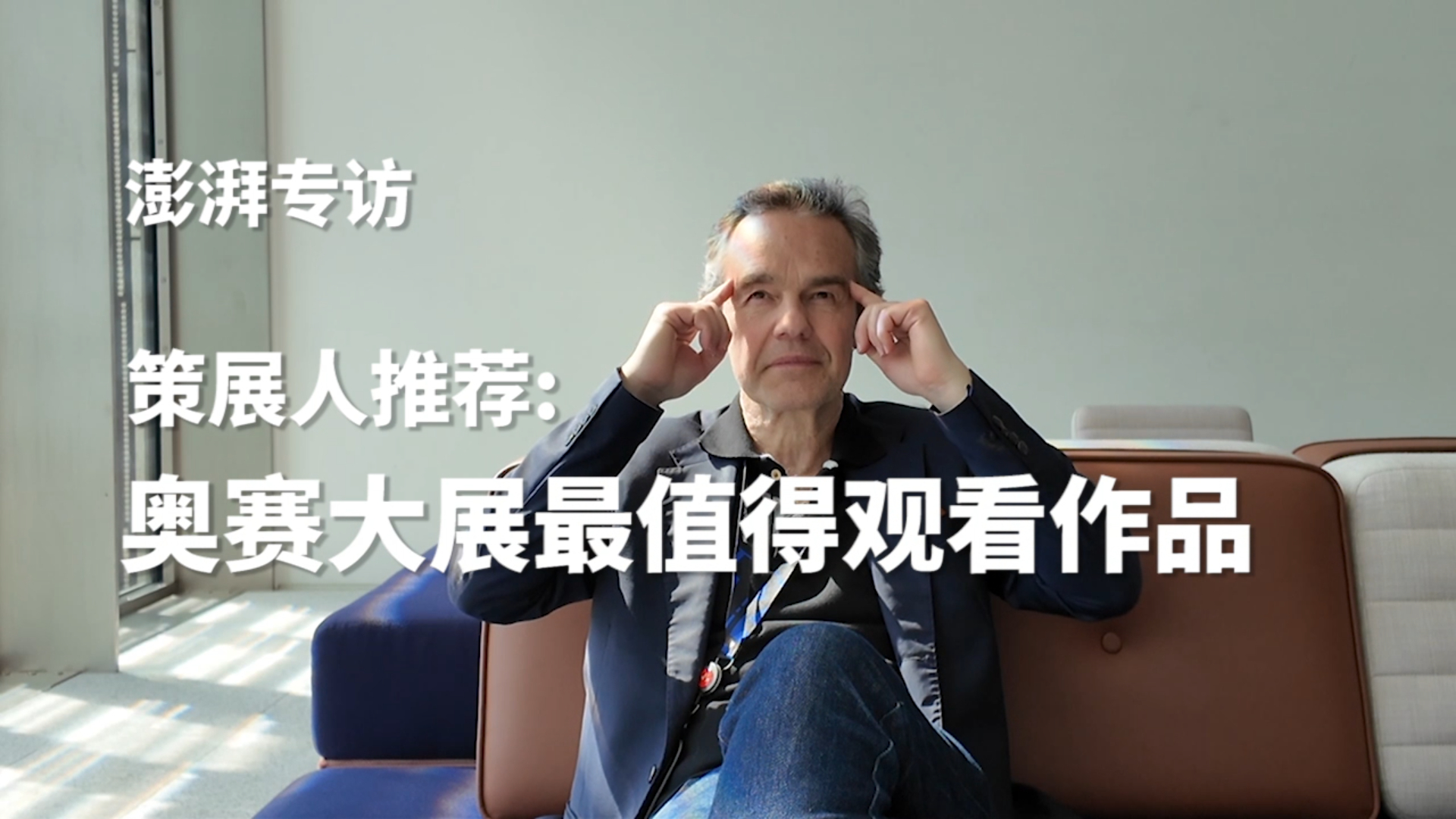

On the occasion of the exhibition of "Creating Modernity" in Pudong, Sylvain Amic, president of the Musee d'Orsay, gave an exclusive interview to "The Paper·Art Review".

"Previous exhibitions held by the Musee d'Orsay in Shanghai or other places often focused on a certain group of artists or a specific period of time. This time in Pudong, Shanghai, we hope to present the 'birth of modern painting' in the true sense. This is an interweaving and resonance between different artists, and a concentrated display of the overall historical process and artistic phenomena." Amick said that he is very much looking forward to the continued cooperation between the Musee d'Orsay and Shanghai in the future.

The exhibition hall on the first day of the “Creating Modernity: Art Treasures from the Musée d’Orsay in Paris”

"The Louvre is in charge of the past, the Pompidou Center faces the future, and the Musée d'Orsay focuses on art from 1848 to 1914, an era that underwent drastic changes. The contemporary world we live in today was born during this period." This is Amick's description of the era covered by the Musée d'Orsay's collection, 1848 to 1914, which is the period covered by Shanghai's "Creating Modernity", a period that "constitutes a profound transition from tradition to modernity."

Sylvain Amic, President of the Musee d'Orsay

Talking about the exhibition: Bringing together masterpieces and presenting many moments in the birth of modern painting

The Paper: How do you summarize and interpret the 107 paintings and sculptures exhibited in the “Creating Modernity” exhibition?

AMICK: An exhibition is a time-limited experience that takes years to prepare but lasts only a few months. This is a very special moment. France played a central role in the world in the 19th century. That's why we worked so hard to curate this exhibition - to make it as comprehensive as possible, to bring together many masterpieces, and to present many key moments in the birth of modern painting.

In this exhibition, the architectural context of the Musée d'Orsay is first recreated. The Musée d'Orsay was originally a railway station - this is meaningful in itself. It was not originally built to display art, but an industrial space.

At the exhibition site, the iconic clock of the Musee d'Orsay allowed visitors to enter the context of the exhibition and also became one of the "check-in points".

The existence of this kind of building provides a unique insight into that era. It is built with iron and steel - in fact, the Orsay Station has more steel structure than the Eiffel Tower. It symbolizes the progress of French industrialization in the late 19th century, and also symbolizes the rhythm and power of an era.

The exhibition unfolds in this industrial architectural imagination: we start from an old world ruled by fixed ideas, religious doctrines and art academy norms, and see how these rules are questioned and deconstructed step by step, thus ushering in the birth of new art.

The exhibition entrance features two works with old-world paradigms: Jean-Leon Gérôme’s “Young Greeks Playing Cockfighting”, 1846 (left), and Alexandre Cabanel’s “The Birth of Venus”, 1863 (right)

The exhibition begins with a group of works that are completely influenced by the French Academy tradition, with idealized nude images, classical mythological characters and composition methods - these pictures have almost nothing to do with real life. However, soon, with the appearance of Courbet, Millet, and later Impressionism, we see "reality" itself enter the painting: natural landscapes, workers, farmers, children on the street, the contrast between the city and the countryside - all these social realities began to dominate the artists' canvases.

Millet's The Gleaners exhibition hall, surrounded by works by artists such as Courbet and Bastien-Lepage

This is not just a change in subject matter, but also a reshaping of the essence of art: no longer expressing an idealized world, but facing the changes and turmoil that are taking place.

At the same time, we can also see how artists constantly reflect on themselves in their self-portraits. They are no longer just the worshipped "creators" in the paintings, but are thinking about their position and meaning as modern individuals in this new social structure. This is a search for identity and also a spiritual confession.

All of this unfolds quietly in the exhibition, constituting a profound transition from tradition to modernity.

The last hall of the exhibition is dedicated to the works of the Nabis.

The Paper: The interweaving of the works presented in the exhibition reminds me of the concept of "image ecology" proposed by Gombrich, which emphasizes that images need to return to their social and historical contexts to gain true meaning. What kind of messenger role do images play in cross-cultural dialogue?

Amick: Images have an extraordinary power. They can touch us directly without the need for words.

Because of this, the power of images is twofold: on the one hand, they can transcend the boundaries of language and culture and immediately generate emotional resonance; on the other hand, this power can also lead to misunderstandings. If it lacks the support of background knowledge and historical context, it may be misinterpreted, misunderstood, or even abused.

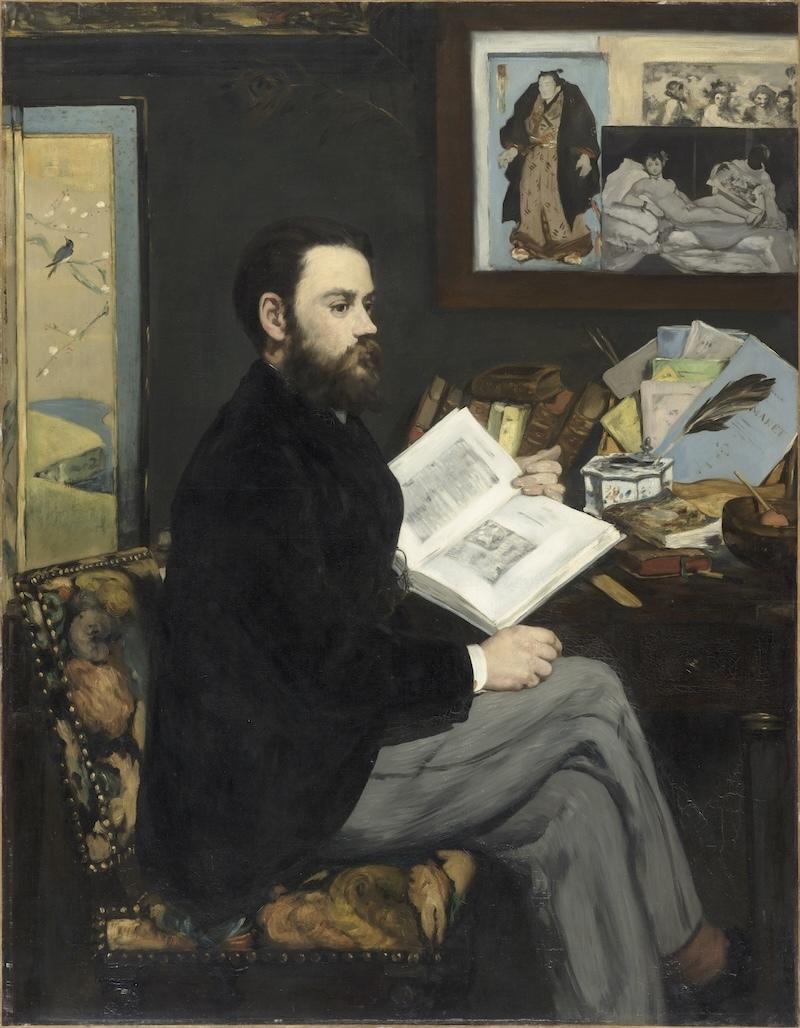

Édouard Manet, Émile Zola, 1868, oil on canvas © photo : GrandPalaisRmn (Musée d'Orsay) / Patrice Schmidt

This is exactly the responsibility of the museum: it is not only a space for displaying images, but also a place to give these images context and meaning. Through their academic training and curatorial logic, researchers and curators in the museum provide audiences with a path to "watch", allowing people to understand why these images were created in this way, when they were produced, and what social context they responded to.

Charles-François Daubigny, Spring, 1857, oil on canvas © photo : RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d'Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

At the same time, images always retain a kind of original, cross-cultural "directness". Just as before the invention of writing, humans have expressed and communicated through images. The power of images is ancient and universal, and therefore must be guided and interpreted.

When we bring these works to another cultural context, such as this time in Shanghai, we are very clear that the audience's reaction will be different because they have their own cultural experience and visual habits. Understanding this difference is a process of getting closer to each other and listening to each other. We try to understand how Chinese audiences view these images with their own cultural background, and they also try to understand the meaning of these works in the French or European context.

Exhibition view, Paul Cézanne, Portrait of Madame Cézanne, 1885-1890, oil on canvas

Every exhibition like this is a two-way process: we take a step towards each other, and the other side also moves closer to us. This kind of mutual understanding and learning between cultures is the most fascinating and precious thing.

On cooperation with China: Re-examining France through the eyes of others

The Paper: This exhibition is the largest exhibition of the Musee d'Orsay in China to date. Can you talk about your impression of Shanghai and your collaboration with the Pudong Art Museum?

Amick: I first came to Shanghai five years ago when I was the director of the Rouen Museum in Normandy, France, and curated an exhibition on abstract art at the Shanghai Minsheng Art Museum. But I have been to China many times in the past thirty years. For me, Shanghai is a very special city, full of modernity and with the power to control the future and destiny.

In 2019, Amick, then director of the Rouen Museum, curated the exhibition "Invisible Beauty" at the Shanghai Minsheng Art Museum. Pictured is him guiding the audience at the exhibition site.

I was in a hurry in Shanghai this time and didn't have much time to visit, but I went to see the West Bund Art Museum to see what my colleagues at the Pompidou Center are doing here. The ongoing exhibition explores the theme of "landscape" and the exhibitors include not only French artists, but also creators from all over the world.

West Bund Art Museum and Centre Pompidou’s five-year exhibition collaboration project, permanent exhibition “Reshaping the Landscape: Collection Exhibition of Centre Pompidou (IV)”, West Bund Art Museum, photo by Alessandro Wang

I am glad to see that there are many cultural projects initiated by French cultural institutions in Shanghai, which never only show one aspect of French culture, but an open artistic vision. This also shows that Shanghai has a high level of understanding and appreciation of art, as well as the important position of art in contemporary society.

We have noticed that the Shanghai public is very interested in cultural projects, art, especially French art, and is eager to see various open and diverse art presentations. Previously, many exhibitions on different eras and cultures have been held here. I am honored that France can participate in it and bring an exhibition of the corresponding level and quality.

Amick (second from left) at the exhibition

At the Pudong Art Museum, we felt the extremely high professional standards and saw the organizer’s outstanding ability to organize major exhibition projects.

Planning an exhibition requires a lot of investment and effort, so finding the right partners is the key to achieving the best results. At present, we have begun to explore future cooperation projects. Although it will take a few years to prepare, we can be sure that we will continue to cooperate with the Pudong Art Museum and may also promote new exhibition projects in other parts of China. We will wait and see.

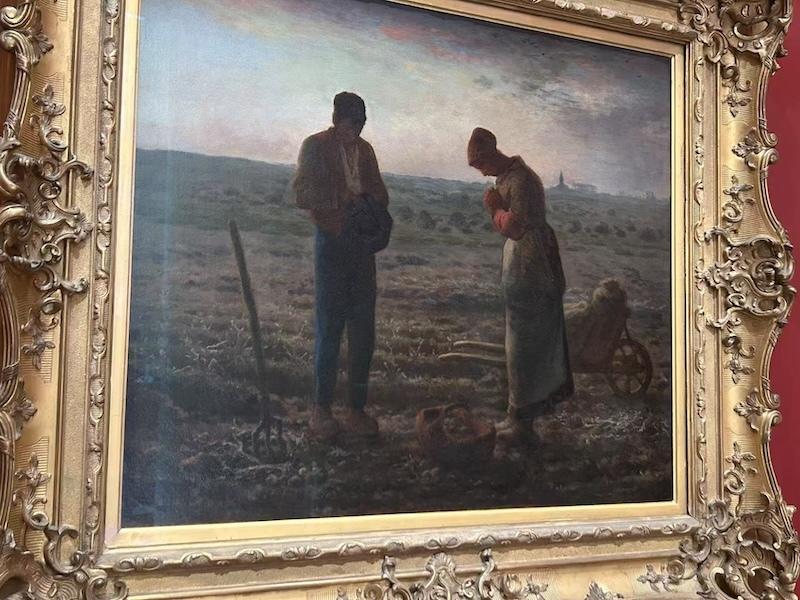

Visitors in front of The Gleaners at Pudong Art Museum

Another important work of Millet, The Vespers, in the Orsay Museum

The Paper: How do you understand a national museum’s responsibility to express itself when facing a “global audience”?

Amick: This is a question I think about every day, and this is the fundamental difference between a "national museum" and an ordinary museum: as a "national museum", we must first face all French people, not just the elite, or Parisians. For this reason, we need to develop strategies to make the exhibitions of the Orsay Museum reach all of France, even in places where there are no museums. For example, a "museum truck" is being built to bring art to regions that have never had museums.

France is diverse, with people from different countries and cultural backgrounds, each with their own experiences and concerns. How can we make all these people from different backgrounds feel at home in the museum—feeling welcomed, treated equally, and taken seriously? This means that before we tell our stories to the world, we must first learn how to communicate with the diversity of France.

The Musee d'Orsay on June 18, 2025

At the same time, the museum has another important mission: to go global. Next year will be the 40th anniversary of the establishment of the Musee d'Orsay. Looking back, our international cooperation is mainly concentrated in Western countries, and has also touched Asia a little, but the cooperation with China is actually very limited, and there is almost no intersection with Africa, the Arab world, and South America.

Therefore, the challenge before us is: how to truly become a "global" museum - an institution that operates around the world and engages in dialogue with the world.

Manet's "Boy with Piccolo" was exhibited in Shanghai in 2004.

This visit to China is of great significance. China is a great country with a long history, a land with a long cultural tradition, and a country with deep cultural ties with France. Moreover, China has a very large population. For us, China is not only a key cultural partner, but also an important window to understand Asia and other regions of the world.

This also means that we need to accelerate our research and deepen our understanding of the exchanges and interactions between France and Asia, and China, during the period covered by the Orsay. At that time, there were artists coming to China, and there were Chinese collectors, diplomats, and travelers coming to France. These cultural connections are real in history, and we need to do more research to understand them. Therefore, this visit to China is not only to establish connections with Chinese audiences, but also to deepen our understanding of our own history - and from here, to other regions that we have not really reached yet.

We need these external eyes to look at French culture and art and discover new meanings in them.

Visitors take photos at the entrance of the exhibition "Christian Krauch: People of the North" at the Musee d'Orsay in Paris, France, on March 20, 2025, local time. The exhibition is the first retrospective of Norwegian painter Christian Krauch outside of Scandinavia and the end of the Musee d'Orsay's trilogy on Norwegian art in the early 20th century. The exhibition will run until July 27, 2025.

Talking about "Impressionism": Re-understanding Impressionism 150 Years after Its Birth

The Paper: Last year, the Orsay organized a series of commemorative projects for the 150th anniversary of the birth of Impressionism. As the leading institution of this "grand narrative", is the Orsay trying to rediscover Impressionism? And sort out the positioning of Impressionism in the global context?

Amick: Taking advantage of the 150th anniversary of the birth of Impressionism, we raised the question "How to understand Impressionism again?"

This is also an opportunity to share these works with as many audiences as possible. Over the past year, we have loaned many masterpieces to various places in France, and in Paris, we have curated an exhibition that looks back to the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874 - trying to show that the birth of this movement did not happen in isolation. For a long time in the past, people have consciously or unconsciously ignored the complex context of the time in order to simplify the narrative.

Exhibition view of “Paris 1874: The Making of Impressionism” at the Musee d’Orsay

Impressionism is a revolution, but it is not just a break. It also has a profound continuity with previous traditions. In other words, it stands at the intersection of "break" and "continuity". What we hope to show is the complexity of this period of history. This is also one of the significances of this Shanghai exhibition: it shows that the struggle between artists is far from a clear-cut camp, but a process of ideological collision and collaboration in multiple schools, which together gave birth to a "new painting".

Therefore, this is also a way for us to re-examine how Impressionism came into being. Impressionism, like all important art movements, deserves our further study. One very interesting angle is its relationship with the world.

Édouard Manet, Woman with a Fan, 1873-1874, oil on canvas © photo : Musée d'Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

For example, its influence from Asian art is well known. But don't forget that it was collectors who helped spread Impressionism around the world. And each time it was "transplanted", a new painting language was born in different parts of the world. It can be seen in Asia, in the United States, and even in the Arab world. Therefore, Impressionism has become a truly global phenomenon. That's why these paintings are so popular and audiences around the world are eager to see them. But I think the research on these issues has just begun.

In 2024, the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo, Japan, will include a hall in its exhibition "Monet's Water Lilies Period" that will display Monet's water lilies collected in Japan.

The Paper: While commemorating Impressionism, how does the Museum of Orsay sort out the influence of its collection on the writing of 20th century and even contemporary art history?

Amick: This also represents how we think about the future of museums and how we connect with the public in the present.

Over the years, we have been strengthening one direction: inviting contemporary artists to have a dialogue with the collection. Because these works have become "image logos" familiar to audiences around the world, artists willing to have a dialogue with them come from all over the world.

For example, we are currently showing an artist from Brazil, Lucas Arruda, who is our first artist from the Southern Hemisphere. He is very interested in the Orsay collection, which is a feeling shared by many artists - because the Orsay collection is not only important, but also always relevant to the present.

Installation view of Lucas Arruda’s “What’s the Use of Landscapes” at the Musee d’Orsay

We also planned a special project called “Le Jour des Peintres”, which took place on September 19 last year. On this day, we invited 80 contemporary artists, aged between 30 and 77, to bring one of their works and place it next to their favorite Orsay works.

Contemporary artists and their works are presented side by side with 19th century art, making us realize that this is not a generational issue, but a strong emotional resonance, and they are also proud to be next to the works of their role models.

"Painter's Day" event poster

More importantly, this is a way for contemporary artists to re-examine past art in their own way, not through academic interpretation, but through a completely new perspective. This is also the direction in which the Musee d'Orsay is paving the way for the future: giving history new vitality through the participation of artists.

The Paper: In your opinion, what is the key to why Impressionism can still inspire such international resonance 150 years after its birth?

Amick: I believe that Impressionism is still worth our continued revisit and exploration, because it is an extremely rich artistic phenomenon and we can always discover new meanings from it.

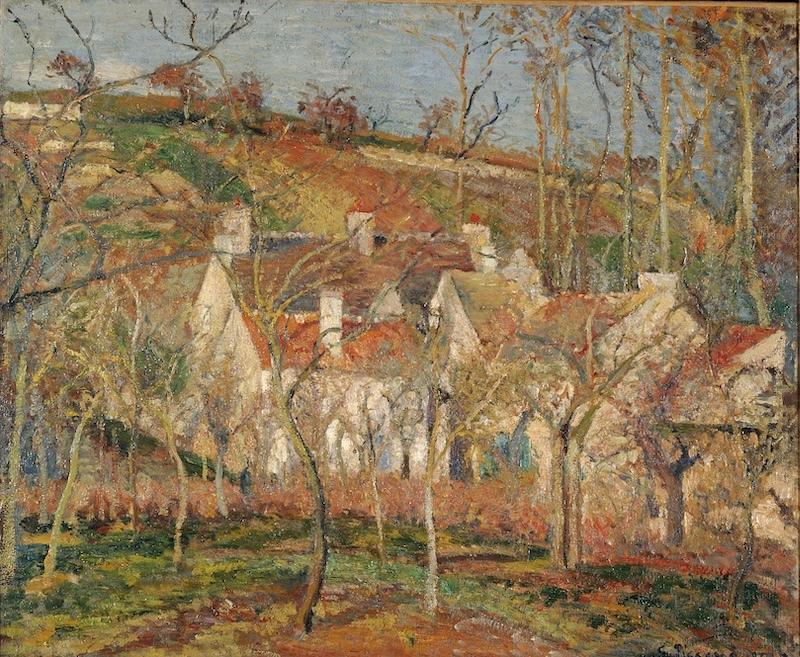

Camille Pissarro, Red roofs of a village in winter, 1877, oil on canvas © photo: Musée d'Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

For example, we are now re-examining Impressionism from the perspective of "climate" and "biodiversity". We realize that the Impressionists were also the first artists to promote nature conservation. They promoted the creation of the first national forest park in France (such as the Forest of Fontainebleau). The concept of "natural park" that we are accustomed to today was actually born in their time in the 19th century - when people began to realize that nature was gradually disappearing and the traditional natural world was under threat.

This is a new interpretation of Impressionism: they were not only pioneers of the artistic revolution, but also forerunners of environmental awareness and "early warnings" who were sensitive to climate and the survival of nature.

Exhibition view, Constantin Meunier, “Black Land”, circa 1893

Of course, there are many other themes worth exploring, such as the role of female artists, which we have already presented in an exhibition; and the topic of modernity. In this exhibition at the Pudong Art Museum, we also presented the status and role of Impressionism through the process of industrialization and urban changes.

I always believe that the most powerful cultural phenomena can always be reinterpreted by generations and constantly respond to current issues. This is the charm of Impressionism - it is far from exhaustive, and it can always bring new surprises and new inspirations.

"Creating Modernity: Art Treasures from the Musee d'Orsay in Paris" exhibition site

Talking about the Orsay: Responding to current issues in a museum centered on the 19th century

The Paper: Compared with other French museums such as the Louvre, which collects ancient art, and the Pompidou, which collects modern and contemporary art, what else makes the Orsay unique besides its collections and research?

Amick: The Louvre is in charge of the past, the Pompidou Center is oriented to the future, and the Musée d'Orsay focuses on a very small period of time - only 75 years: from 1848 (the February Revolution in France) to 1914 (the outbreak of World War I). This period sounds short, but its density and importance are extremely high: science, art, politics, economy... almost everything has undergone drastic changes. The contemporary world we live in was born during this period.

Therefore, the challenge we face is how to open a "narrow" window of time and show the public its decisive significance in understanding contemporary society today and even in facing current problems.

"Art in the Streets" special exhibition at the Musee d'Orsay in Paris

This period has both glory and shadow, but it has almost laid the foundation for the present and the future. Climate issues were first recognized in the 19th century; colonial issues are also an important legacy of this century. But at the same time, this is also the era of the invention of vaccines, the birth of movies, the laying of railways, and the beginning of the emergence of technology and modern lifestyles.

This is a highly charged and complex period, full of hope and contradictions, and it is not just history, it continues to affect us. Therefore, in-depth research on this period is crucial to our understanding of the world today.

The Paper: As the "temple of 19th century art", how can museums transform from "guardians of classics" to "storytellers of the future"?

Amick: It is true that the primary mission of a museum is to preserve – but preservation is meaningless if it is not used by people.

Even though people in the past made great efforts to preserve art, we still need to ask ourselves: Is this concept still relevant today? Therefore, the way we work is to make the museum as "contemporary" as possible - by responding to today's problems, showing how the collection, art history and the history of that era are still important resources for us to understand the world and draw inspiration.

For example, the status of women in art and society was a very tense issue in the 19th century. Today, this issue is still the focus of public discussion in Western society and even in Asia.

"Creating Modernity: Art Treasures from the Musee d'Orsay in Paris" exhibition site

We can revisit this question by drawing on the collection itself and the history of the artists and the models. In this way, a contemporary issue can be addressed in our museum, which is centered on the 19th century. This is a vivid example of how we can make the museum "up to date".

The Paper: In recent years, the Musée d'Orsay has also made frequent moves in the digital field, such as virtual exhibitions, social media operations, and immersive cooperation projects. Do you think digitalization will change the "power structure" of museums?

Amick: Digital technology is an extremely valuable tool, and we are constantly expanding related practices. For example, in this exhibition, visitors can use virtual reality to personally "travel" to the site of the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874 - this is an experience that cannot be achieved in real exhibitions.

Scene from the "Paris 1874 Impressionist Night - Immersive Exploration Experience"

It is a channel to the past and a way to help us better understand the context of the exhibition. We mentioned earlier that to understand the works, we need to understand the context of the times in which they were created, and virtual reality provides such an opportunity.

For us, this technology also provides a new possibility: to allow a wider audience to access art without having to use the original work every time. Artworks cannot appear in multiple places at the same time, but technology can. For example, this immersive experience is currently appearing in Dubai, France, the United States and other places at the same time. Relying on the same technology platform, audiences can share the same experience in different locations.

Of course, a real work of art is a kind of "one-time" encounter, and the advantage of virtual technology is that you can repeat it many times, become more familiar with it, and be more proactive in exploring the details of art history.

I am not at all worried that this technology will weaken the audience's feelings about the artwork itself - photography, film, television, and the Internet in history have never replaced museums. New technologies will not replace them either. On the contrary, they are extremely powerful auxiliary tools to help us understand art more deeply and in a more three-dimensional way.