The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York is hosting an exhibition titled "The Diverse Lives of the Nakagin Capsule Tower," dedicated to the Nakagin Capsule Tower, designed by Japanese architect Kisho Kurokawa. The tower, built in Ginza, Tokyo in 1972 and demolished in 2022, consisted of 140 capsule-like "micro-apartments," each approximately 10 square meters in size and equipped with a television, refrigerator, and bed.

The exhibition presents a 50-year history of the building through background materials, original drawings, archival footage, and a fully restored capsule unit. It is not only a retrospective of the work of Japanese architect Kisho Kurokawa, but also a reflection on the life of architecture, urban transformation, and adaptive reuse.

The A1305 capsule unit of the Bank of China Capsule Tower on display

The interior space restored at the exhibition site Source: MoMA

The exhibition combines original drawings, photos, archival videos, etc.

It is reported that the MoMA exhibition displays capsule unit A1305 of the Bank of China Capsule Tower, one of only 14 capsules that have been restored to their original state. MoMA purchased this unit in 2023 after the building was demolished. The capsule was originally located on the top floor of the tower. During its restoration, original components salvaged from other units were used, including a complete set of audio-visual electronic equipment that was optional at the time. The capsule is exhibited together with original drawings, photographs, promotional materials, archival films and recordings, interviews with former residents, an interactive virtual tour of the building, and the only surviving architectural model from 1970 to 1972. The exhibition traces the project's ever-changing story - from its initial marketing positioning as micro-apartments for urban business people to its gradual decline and eventual demolition. It also showcases the ideals of the "Metabolism School" - growth and replacement.

Architectural models at the exhibition

The Bank of China Capsule Tower, built in 1972

In 1972, the Nakagin Capsule Tower, a futuristic building, stood tall in Ginza, Tokyo. As a landmark practice of postwar Japan's "Metabolism" movement, Kurokawa Kisho (1934-2007) rooted his design philosophy in biological metaphors—metabolism, like a living organism.

To understand the disruptive nature of the Nakagin Capsule Tower, we need to revisit the concepts of Metabolism. This avant-garde architectural movement, born in Tokyo in 1960, was "the first non-Western architectural revolution" to emerge from the devastation of post-World War II Japan. Led by Kenzo Tange, its core members, including Kisho Kurokawa, Kiyonori Kikutake, and Fumihiko Maki, used the biological metaphor of "metabolism" as a metaphor, proposing that architecture should dynamically grow, evolve, and decay like an organism.

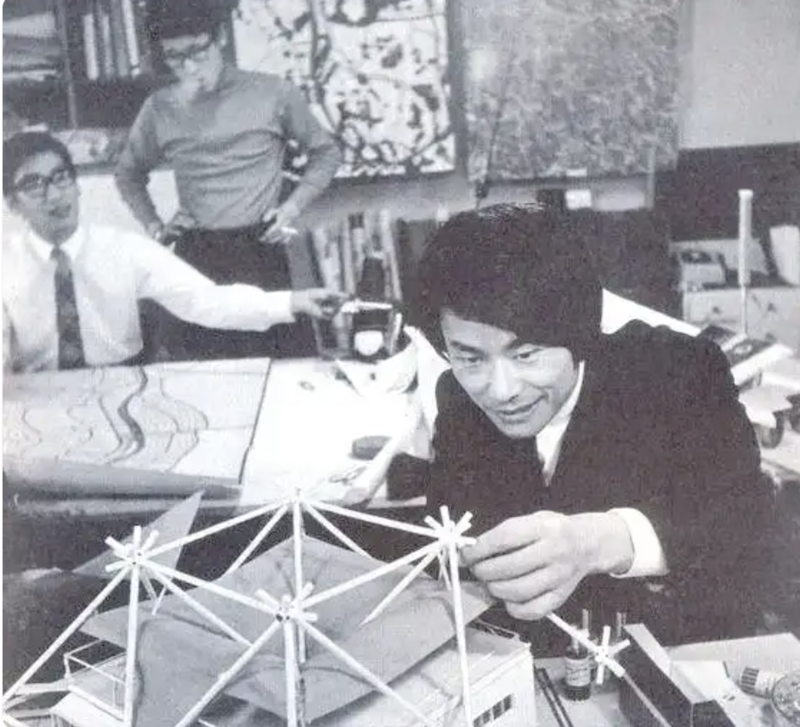

Architect Kisho Kurokawa

Kisho Kurokawa (1934-2007) was born into a family of architects in Nagoya. His father and brother were both architects. As a teenager, he witnessed the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and the Tokyo air raids, witnessing the reduction of wooden cities to rubble and realizing the inherent impermanence of architecture. In 1959, at the age of 25, Kurokawa published From the Mechanical Age to the Life Age, proclaiming his vision of transcending Le Corbusier's "machine for living." The following year, he became the youngest core member of the Metabolism movement, advocating that architecture should, like living organisms, undergo "a struggle between the old and the new, a dynamic alternation," using technology to achieve the disassembly, proliferation, and addition of space.

Everything was changing in post-World War II Japan. Massive migration, new cities rising from the ruins, and explosive economic growth were all part of the landscape. The future was arriving faster than anyone imagined, and architecture couldn't keep pace. Thus, the Metabolism school was born, a group of young architects' architectural response to the monotony of the city. Metabolism believed that cities and architecture were not static, but rather dynamic processes, like biological metabolism. They emphasized the importance of time in cities and architecture, clarifying the cycles of each element. Growth and renewal were central concepts.

Nakagin Capsule Tower at night, 2016 © Jeremie Souteyrat Source: MoMA

The Metabolists envisioned a hierarchical urban model—a "megastructure" serving as a permanent framework, housing interchangeable "capsules." Kurokawa Kisho took this concept to its extreme, with the Nakagin Capsule Tower serving as an experiment in this concept.

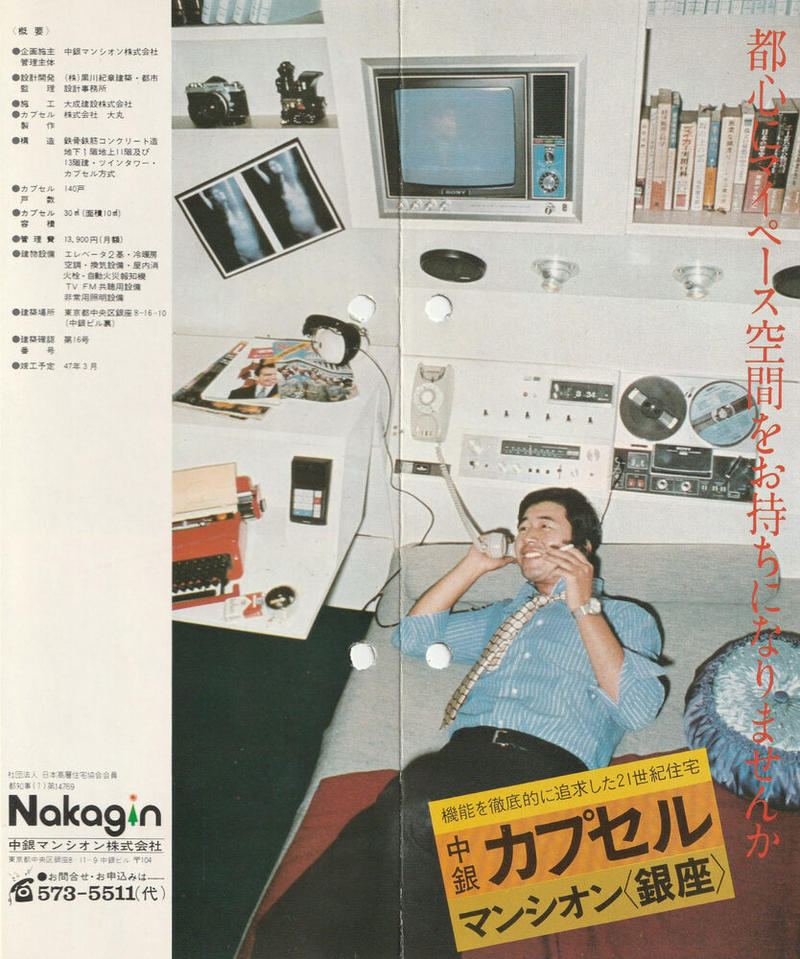

Cover of a Nakagin company brochure from 1971. Photo: Tatsuyuki Maeda/Nakagin Capsule Tower Conservation and Restoration Project, Tokyo, Japan

In 1972, this tower, consisting of two concrete cores (11 and 13 stories) supporting 140 regular hexahedral cabins, stood in Ginza, Tokyo, and was a physical declaration of technological utopia.

The building's core consists of two concrete cores, to which 140 prefabricated "capsules," each just 10 square meters in size, are bolted like cells. Kurokawa boldly envisioned that these capsules would be replaced and upgraded every 25 years, allowing the building to grow and evolve to meet changing needs. He once stated, "This building is not an apartment building."

Data map of the interior space, similar to a space capsule.

Internal structure data source: archdaily

Inspired by Soviet spacecraft, each 2.5x4 meter prefabricated capsule is factory-fitted with minimalist interiors (folding cabinets, a Sony television, and a radio). High-strength bolts anchor the core, allowing for independent replacement. Kurokawa envisions the capsules as cells that can be freely multiplied or deleted—as young people influx the city, the tower can quickly "clone" new buildings; as demand wanes, the units can be disassembled and relocated. This dynamic model attempts to address Tokyo's rapidly accelerating urbanization.

Unfortunately, there is a gap between ideal and reality. Although the cabin is as complete as an "urban astronaut's space capsule", the living experience here is less than ideal due to a variety of reasons, such as lack of privacy, hot and humid indoor space, and light pollution from the surrounding highways.

Problems such as water leakage and aging pipes cannot be solved

After years of disrepair, it gradually showed a sense of desolation Source: archdaily

Because asbestos was used extensively as a fireproofing and insulation material during construction, over time, wall sloughing caused asbestos fibers to leak. In some areas, concentrations far exceeded Japanese safety standards, making it a Class I carcinogen. The high cost and operational risks of asbestos removal were the overriding factors in the decision to demolish the building in 2021. Furthermore, drainage pipes were designed into the narrow gaps between the capsules. Chronic leakage caused corrosion in the four high-tension bolts securing the capsules, severely degrading their strength. An attempt to repair and seal the structure in 1985 continued, but continued deterioration caused corrosion in the concrete core, rendering it unable to meet Japan's earthquake resistance standards, which have been revised several times since 1981. The original plan was to replace the capsules every 25 years, but they eventually became obsolete and forgotten. Many capsules are now used as warehouses and offices, or as short-term accommodation for architecture enthusiasts. The envisioned "individual replacement of capsules" proved impractical; repairs would have required the sequential removal of capsules, starting from the top floor, a complex and complex process.

A 2006 assessment showed that renovating a single capsule would cost 6.2 million to 6.41 million yen, and total repair costs (including asbestos removal and plumbing updates) would be 2 billion to 3 billion yen. In comparison, demolishing and rebuilding an ordinary apartment would be more economical.

In 2014, the owners and residents launched the "Nakagin Capsule Tower Preservation and Reuse Project," which aims to restore and revitalize 23 capsules in good condition. Some are now displayed at the Wakayama Prefectural Museum of Modern Art and the Saitama Museum of Contemporary Art in Japan, while others are being transformed into RV capsules and exhibited in cities like Nagoya and Osaka, or even shipped overseas to museums.

A capsule unit exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art Saitama, Japan © Museum of Modern Art Saitama

The demolition of the Bank of China Capsule Tower appears to be due to technical flaws, economic difficulties, and governance failures, but the underlying cause lies in utopian architecture's collective blind spot in long-term operational and maintenance mechanisms. However, while the building is gone, its 23 capsules have become "seeds" scattered around the world, now part of art galleries and museum collections. This fragmentation perpetuates the Metabolist philosophy of "regeneration"—when a building cannot survive as a whole, its cells can be reborn as cultural symbols.

It forces people in the city to think again: in an era when houses can be demolished and rebuilt, is it possible to design more creative metabolic cycles for old buildings?

The exhibition will run for one year, ending on July 12, 2026.