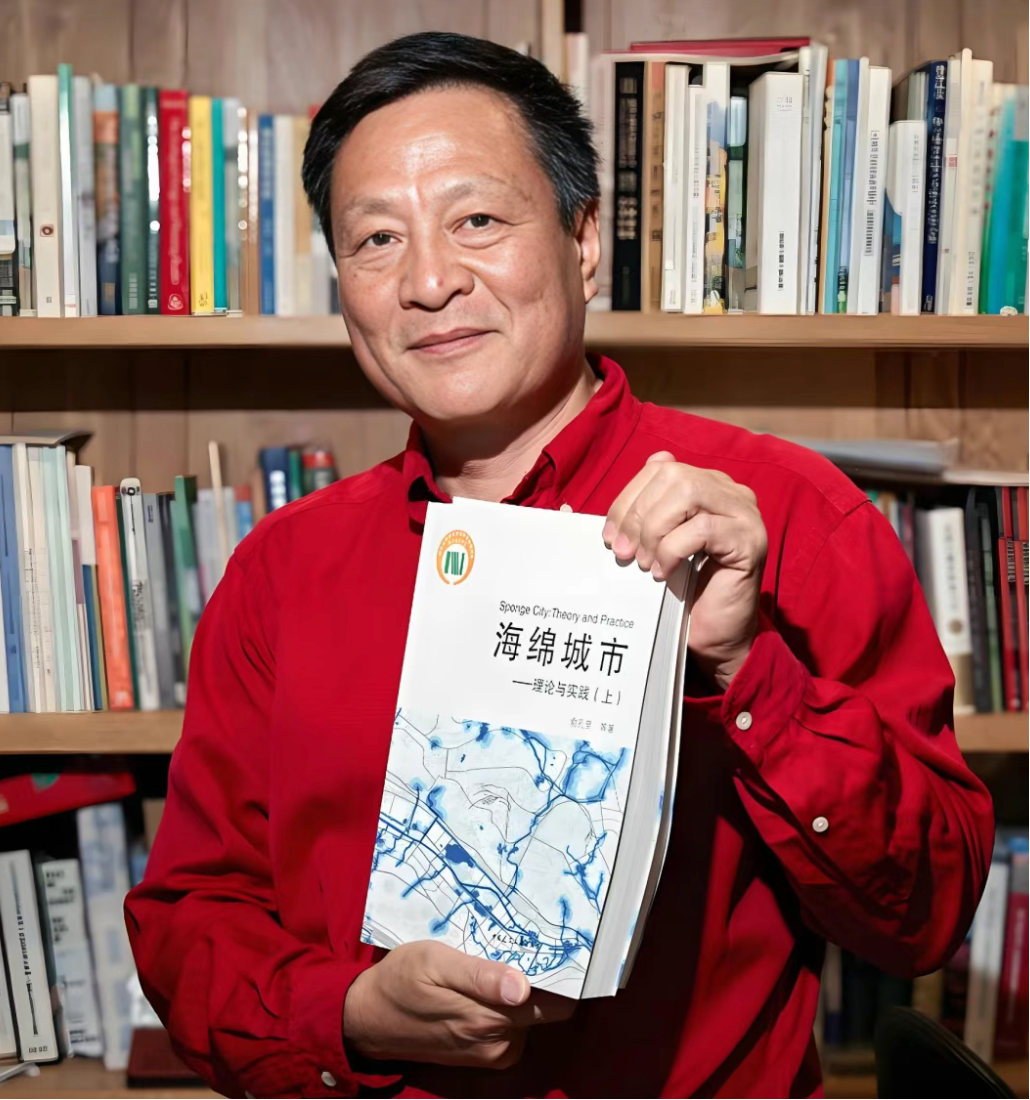

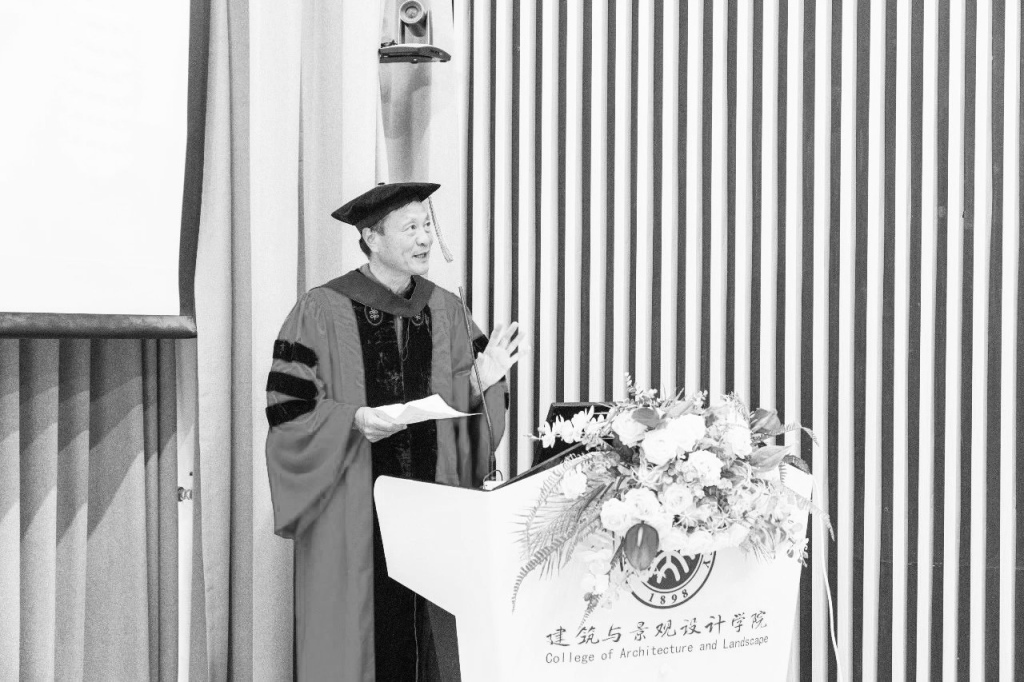

On September 23rd, local time in Brazil, Professor Yu Kongjian, Dean of the School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture at Peking University, tragically died in a plane crash at the age of 62. In June of this year, Professor Yu Kongjian delivered a speech at the Peking University School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture graduation ceremony titled "Returning to the Mortal World," calling for integrity and common sense, which resonated deeply within the architectural community. The Paper is republishing the full text of that speech in commemoration.

Yu Kongjian

Returning to the Mortal Body : Yu Kongjian's Speech at the 2025 Peking University School of Architecture and Landscape Design Graduation Ceremony

Dear Class of 2025,

Today marks a crucial moment in your lives. On this campus, woven with dreams and sweat, we welcome this ceremonial farewell. As your teacher, a designer and visionary who constantly walks the line between the field and the classroom, I stand here not to offer flowery clichés but to offer you a message that may not be fashionable, but is profoundly important: "Return to the mortal realm."

The phrase "mortal" may sound bland, even slightly derogatory, as if it were a compromise with mediocrity. But let me tell you, in this era fraught with challenges—global climate change, urban-rural social transformation, the shifting landscape of civilizations, and especially the rapid development of AI—for those of you who are about to graduate from university, enter society, and enter the real world, these four words precisely represent your most scarce and valuable abilities.

What does "unaided vision" mean? It's seeing the land, feeling the scent of the water, hearing the sighs of ordinary farmers, and feeling the warmth of the grass roots. It's using your unfiltered intuition, experience, and body to measure the reality of a place, rather than relying solely on models, parameters, satellite imagery, and AI.

Just a few days ago, I returned to school from one of the most remote villages in my country. Before I could even recover from my shock, a classmate enthusiastically greeted me, "Teacher, you're tanned again!" I smiled and replied, "Yes, two weeks of fieldwork have dragged me back from screens and meetings to the real world, allowing me to rediscover my own mortal self."

Do you know what I saw?

My air-conditioned car sped along the highway, and outside the window were eye-catching slogans and grand renderings: a multi-billion-dollar water diversion project was about to begin, bringing clean water from the mountains to dilute the polluted river. Nearby, pollution-removal vessels diligently cleared algae and water hyacinths, spending tens of millions annually. Meanwhile, within a few hundred meters of both banks, pig farms in villages were being demolished and relocated, at a cost of billions. All of this formed a magnificent picture of modern land ecological governance.

I am suspicious!

So I abandoned my car and walked upstream, following a stream. The air was thick with a pungent odor, and dead fish and dying frogs floated on the surface. I crawled into a farmer's pigpen and saw a steady stream of fertilizer flowing out. What should have been a treasure for the fields had now become a source of pollution. And in the rice paddies nearby, villagers were applying heaps of white fertilizer—a convenient and inexpensive chemical fertilizer.

Further ahead, there's a stretch of abandoned farmland. A villager said helplessly, "We can't grow cash crops or trees on this land. It's designated 'basic farmland,' so we can only grow grain, and even then, we're losing money." I asked, "Can it be transformed and restored to wetland?" He shook his head, "The red line has been drawn, and it can't be moved." It turns out that this is the farmland indicator line drawn by an expert using GIS technology, and the red line for cultivated land stretches from the steep slope all the way to the center of the river...

I continued up the mountain, where a newly built dirt road spiraled upwards, ending at a newly constructed pig farm. It turned out that, in an effort to "relocate" the pigs, originally located by the river, had been moved to the top of the mountain. What did this entail? It meant blasting rocks, building roads and water supply, and completely destroying the natural vegetation and streams.

Questions echoed in my mind:

Why can’t the money from collecting blue algae be used to help villagers build a manure collection system?

Why can’t we return fertile water to the fields and turn waste into treasure without using even a fraction of the water diversion project?

Why can't we restore the "basic farmland" along the river and on the hillsides into more abundant ponds with multiple ecological functions, allowing nature to recycle nutrients and purify the water, and provide habitats for fish and frogs, and a place for birds to reproduce?

Are we mesmerized by the beautiful countryside and sophisticated technology of utopia? Have we forgotten that many problems can be solved with practical experience and common sense?

We pursue "intelligence," "standardization," and "big data governance," but those algorithms fail to see the dead fish or the hardships of farmers. We develop cutting-edge technology, but ignore the simplest principles of the land: those who cultivate it understand it, and those who use it cherish it. While we paint a blueprint worth hundreds of billions on paper, in reality, we silence the land and the farmers.

Dear students, today you are leaving campus and entering society. You will join the vast scientific and technological community of over 2,000 graduates from our college, including those with master's and doctoral degrees. Some of you may become decision-makers on multi-billion dollar projects, chief designers of GIS systems, commanders of "smart land" initiatives, and promoters of smart agriculture. You will possess knowledge, power, and a grand vision, possessing the capital and potential to transcend the mortal realm.

However, please remember: a truly grand blueprint is not about how large the investment is or how grand the construction is, but about how many lives can truly benefit.

Don't confine yourself to your office, your air-conditioned car, and your reports. Get out there—ask the villagers what they want, smell the earth, see if there are lively fish and shrimp in the stream, and see if the children are playing safely and happily. Only with the seemingly "ordinary" eyes can you truly connect with heaven, earth, and humanity and make informed judgments.

Harbin Qunli National Urban Wetland Park / Turenscape Design

Shenyang Jianzhu University Rice Field School

May you still keep these “mortal” eyes, a body willing to bow your head and bend down, and an ordinary heart willing to listen to the voice of the land and the people in your future journey.

May you not only paint a magnificent blueprint for our beautiful homeland, but also preserve the warmth and humble lives of the fields. May you, with this mortal eye's perception and understanding, survey the mountains and rivers, and realize your ideals, truly ensuring that knowledge, technology, and power take root and benefit all.

I would like to share this with you and wish you a bright future!

(Source: Peking University School of Architecture and Landscape Design)