"Everyone is an artist!" "Art makes life more interesting than art itself!"— Where did these subversive slogans come from? Who first proposed them? What radical artistic experiments and ideological trends do they embody?

On September 25th, the West Bund Art Museum in Shanghai opened its special exhibition "Fluxus, by Chance!", offering a glimpse into the mystery. This exhibition, the first in a new five-year collaboration between the West Bund Art Museum and the Centre Pompidou in France, also marks the first comprehensive exhibition of Fluxus in China. The Paper observed that the exhibition, through over 200 works from the Centre Pompidou's collection, traces the history of Fluxus, a highly avant-garde and subversive 20th-century art movement, extending its exploration of current issues such as the boundaries of art.

West Bund Art Museum and Centre Pompidou collaborate on a five-year exhibition project, featuring the special exhibition "Accidental! Fluxus!"

Fluxus, originating in Europe and the United States in the late 1950s and early 1960s, is one of the most avant-garde and rebellious movements in art history. While inheriting the anti-rationalist spirit of World War I Dadaism, it more radically broke down the boundaries between art and life, and between the elite and the masses. Art need not be confined to expensive canvases or sculptures; everyday objects like boxes, clothes hangers, games, and even silence and breathing can become artistic mediums.

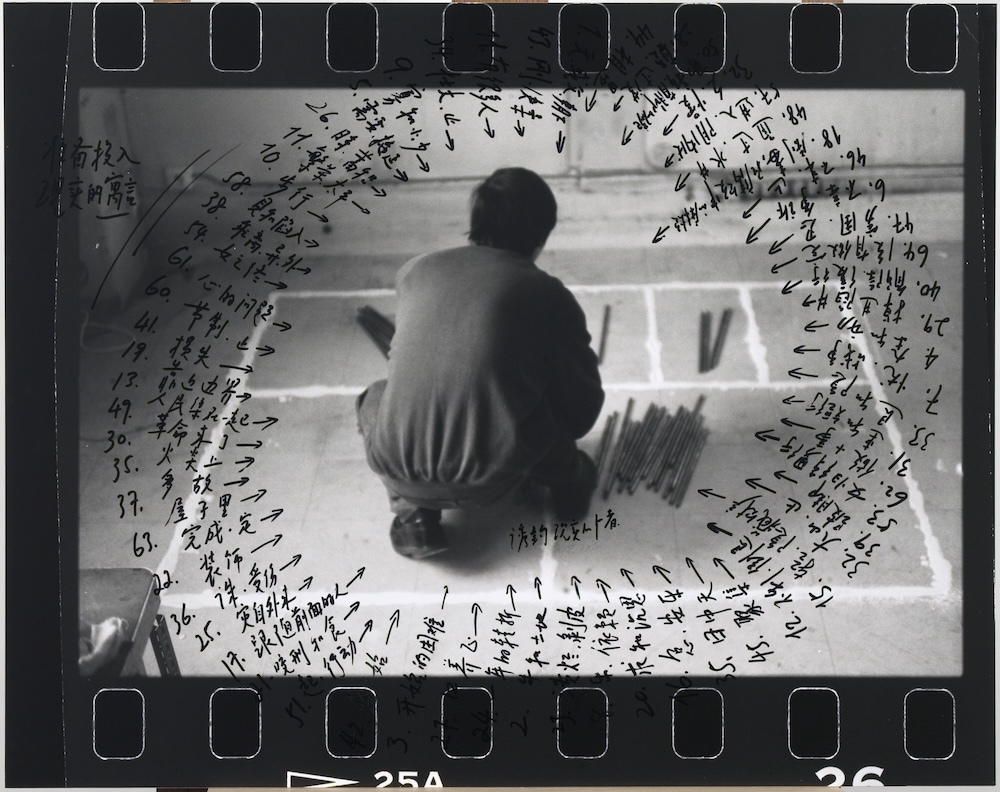

Huang Yong Ping, Untitled, 1991-1992

Regarding the meaning of the exhibition title, "By Chance!", Frédéric Paul, curator of the Centre Pompidou in France, told The Paper: "The title has two meanings: one is 'chance, chance,' and the other is 'chance, opportunity.'" The concept of "chance, chance" is present in Surrealism and even Abstract Expressionism, the contemporary movement of Fluxus. Fluxus is also closely related to poetry, performance art, and music. These slightly performative creative methods involve a lot of uncertainty, and their final presentation is often in the form of interpretation, which also involves uncertainty.

West Bund Art Museum and Centre Pompidou collaborate on a five-year exhibition project, featuring the special exhibition “Accidental! Fluxus!”. Exhibition view of the first chapter at West Bund Art Museum. Photo by Alessandro Wang.

The connection between Duchamp and John Cage

The exhibition begins with a photograph by Man Ray of key members of the French Dada movement taken in 1922. Although the young people in the photo do not appear to be subversive, they were the headlines of their time. This photo also brings out the connection between Dada and Fluxus, which took place half a century apart.

Man Ray, The Dada Group, circa 1922. Digital print from the original. Man Ray is pictured in the lower left image.

Interestingly, Duchamp seems to have a special presence in the exhibition, being mentioned repeatedly, for example, in Mathieu Mercier's interpretation of "Box in a Suitcase," Man Ray's photograph of him playing chess, and "Three Standard End Meters," a tribute to Duchamp by Shanghai children, but he has no actual works on display.

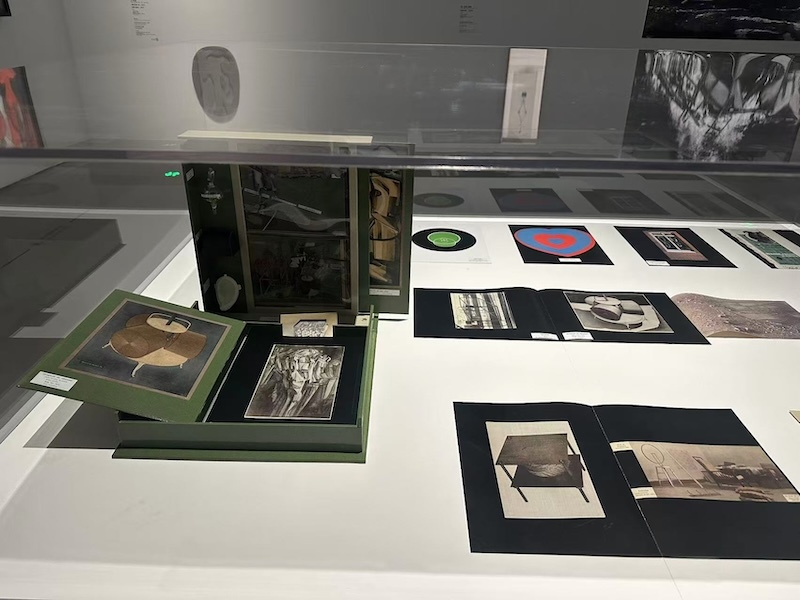

Matthew Mercier, "By or Through the Hands of Marcel Duchamp or Rose Sélavy (Box in a Suitcase): A Gallery in a Box," 2015

While Duchamp seems omnipresent, the curator believes the true linchpin of Fluxus was John Cage, the mentor of several of its most iconic artists, particularly Lamont Young, Brecht, and Yoko Ono. "Cage and Duchamp crossed paths; they met in 1942, and it was this exchange that nurtured Cage's ideas. But I think Cage's approach was more open, while Duchamp is somewhat like an enigmatic 'sphinx,'" says curator Frederic Paul. "This gives Duchamp a presence that's both strong and subtle."

Installation view, Robert Ferrio, The Equivalence Principle: Well Done, Badly Done, Not Done, 1968 (left)

Through 11 chapters, the exhibition traces the ideological roots of the early avant-garde movement, reconstructing the spatial and temporal network of Fluxus' global spread, and gradually delving into its core. The chapter "Keep Silent" pays tribute to John Cage, who, having initially studied under the musical master Arnold Schoenberg, later infused randomness into his music and painting. "Keep Silent" takes its name from a Cage piece, "4 minutes and 33 seconds," which requires no instrumentation.

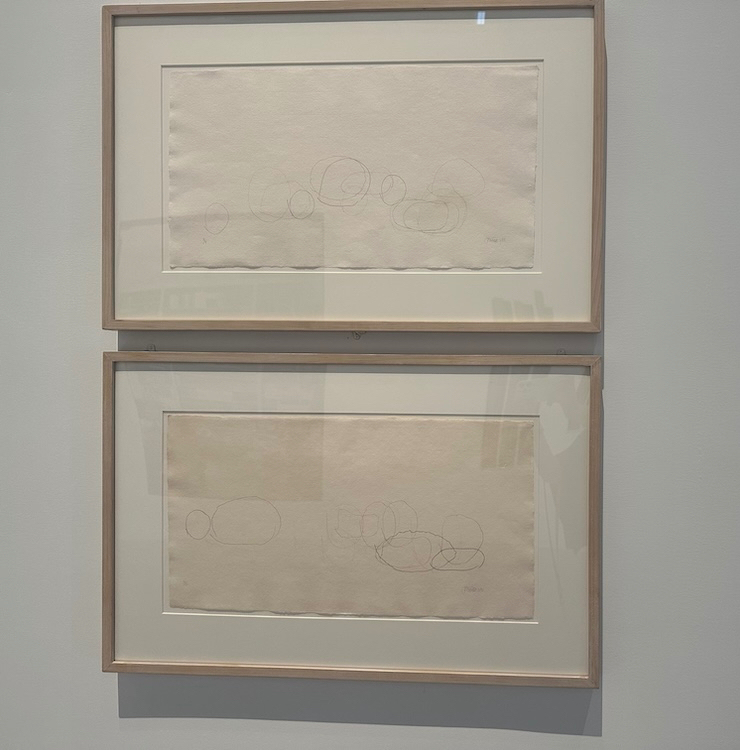

John Cage's "Ryoanji Temple, Kyoto"

This section features Cage's series of sketches on Japanese paper depicting the "dry landscape" at Ryoan-ji Temple in Kyoto. The pencil marks, sometimes thicker, sometimes thinner, sometimes precise, sometimes blurred, leave traces on the white space of the paper, creating a transformation of emptiness, nothingness, and silence. Cage's visits to Ryoan-ji Temple and his exploration of Zen principles also had a decisive influence on him. Cage employed the same principle in his drawings, randomly dropping a string onto a piece of paper to determine the subject of his painting.

John Cage's "Rope"

As for John Cage's identity, in addition to being a composer, poet, and artist, he is also an expert in mushroom research, which is responded to in this chapter with a huge mushroom sculpture.

Exhibition view, Sylvie Fleury, Mushroom U Gweiss A110 Green-Red Medium 1003-M, 2008. A question posed by the museum staff on the ground floor prompted the audience to reflect on the concept of art.

In fact, many members of the Fluxus movement were not traditionally considered “artists,” but rather came from fields such as chemistry, economics, music, design, and anthropology. These interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary creators broke down the “professional barriers” of artistic creation and attempted to redefine the relationship between art and life, and between art and its audience.

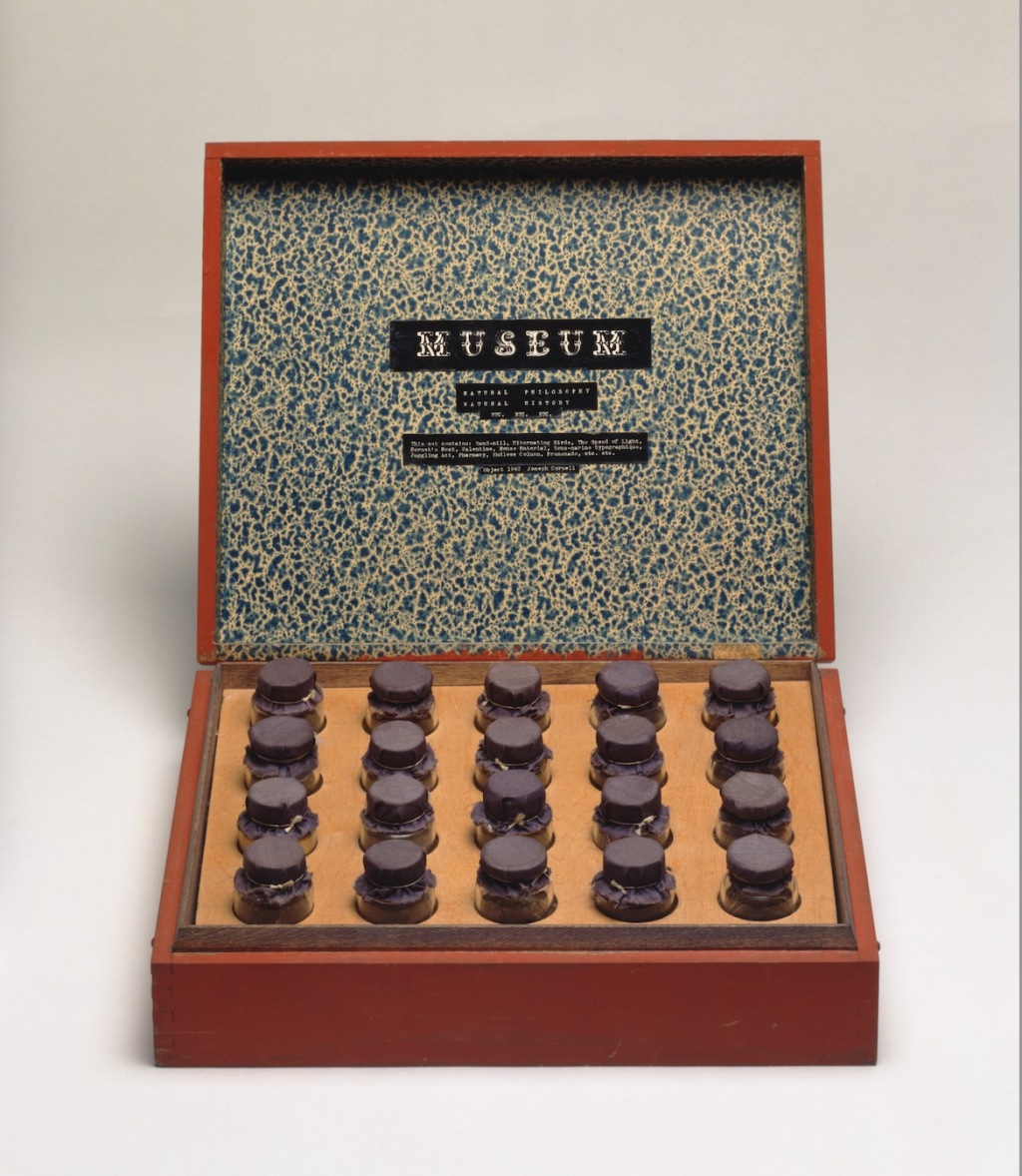

Joseph Cornell, The Museum, 1942

In it, music is a special existence.

Music dematerializes artworks while extending them through time. "We don't know exactly what 'music' is—the sounds we hear, or the score itself as the 'original,'" says Frederick Paul. "I think there's this idea that there's a beginning, the score, which is in a sense the instructions; and there are multiple endings, depending on how they are performed. It therefore has a theatrical dimension."

Exhibition site

A discussion on the boundaries between Brecht and his works

Is the “original” of a piece of music the score itself, or its interpretation?

This question is also addressed in this exhibition, George Brecht's work "Three Arrangements." This work was previously featured in the West Bund Art Museum's 2019 inaugural exhibition, "The Shape of Time: An Exhibition from the Centre Pompidou Collection (I)," using objects selected by Brecht himself. This time, the curators chose to return to Brecht's principles: no longer confined to "original objects," but to re-discover everyday objects in Shanghai that have the same function and use them to "perform" this "score."

2019, permanent exhibition "Forms of Time: Collection of the Centre Pompidou (I)", West Bund Art Museum, exhibition view

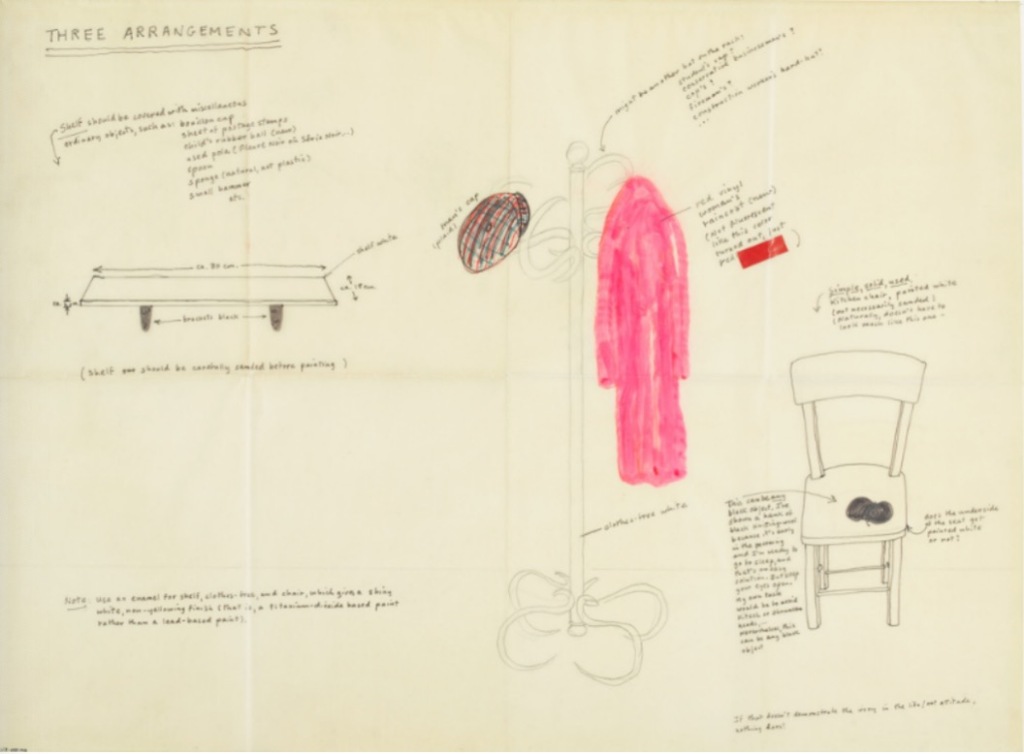

The "score" is the artist's sketch. Extremely concise, it provides only clues for execution, but leaves the freedom of interpretation to the scene—a floor-standing coat rack, a red raincoat, a white shelf supported by black brackets, and the objects to be placed on the shelf; an ordinary chair, with a black ball placed on it.

Bertolt Brecht, Sketches for "Three Arrangements", 1962-1973

"The objects you see here were found locally by the museum based on the artist's sketches. Take the 'Ship of Theseus'—if every part were replaced, would you still consider it Brecht's original work?"

The museum posed these questions on the ground in front of "Three Arrangements." However, the museum offered no answers, leaving the audience to ponder them. Throughout the exhibition, there are many more such questions, yet the museum remains silent, leaving the audience with more room for reflection. This "space for reflection" is precisely the essence of the Fluxus movement.

This discussion extends to the field of visual art. Rather than providing the audience with a fixed work, it is better to say that Brecht raised a proposition: where are the boundaries of the work?

Brecht's "Three Arrangements" at "Accidental! Fluxus!"

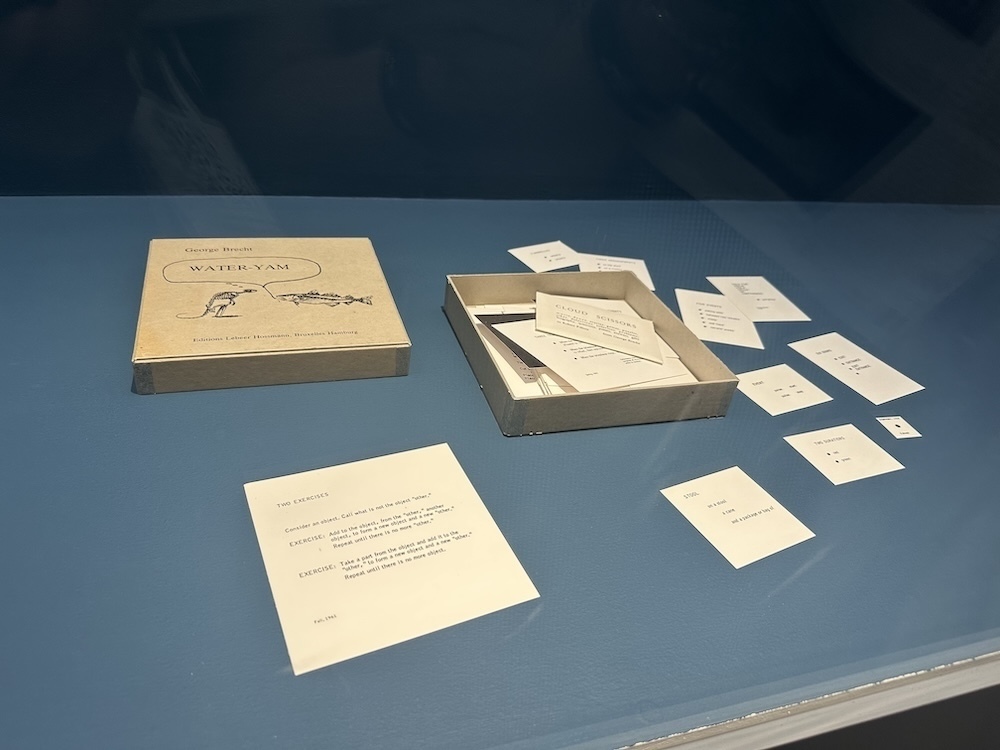

Brecht is undoubtedly one of the most representative figures in the exhibition. He appears throughout the exhibition, and can be seen through projections before the audience even enters the exhibition hall: the cards included in the work "Water Yam" are essentially instructions or musical scores, used to trigger simple and direct performances.

Bertolt Brecht's Water Yam

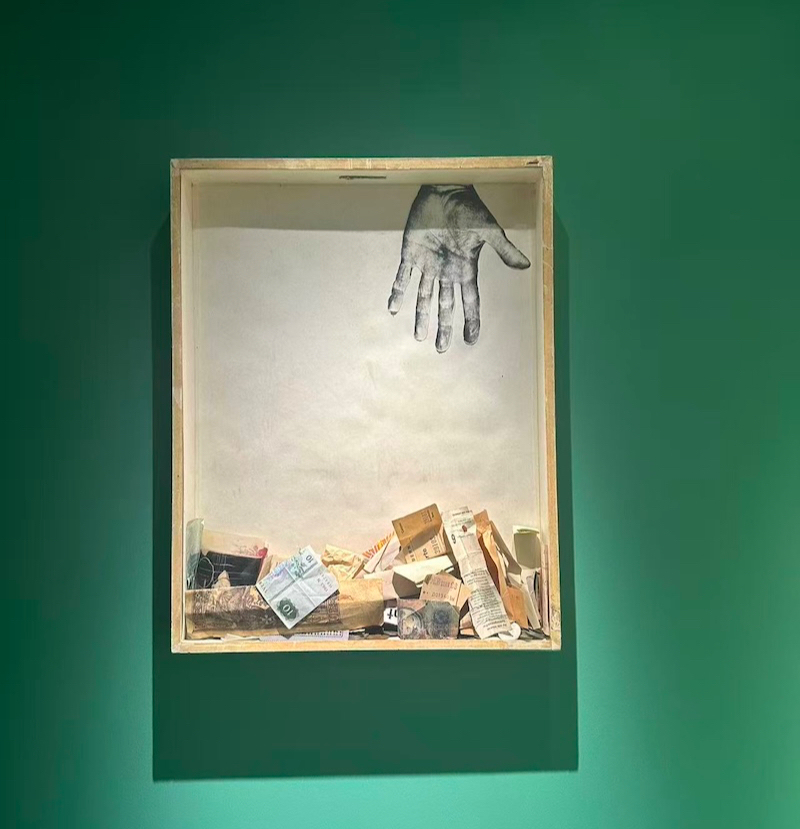

Brecht’s presence is particularly poignant in the second section, “How Did They Meet?” The work “Lichtenstein’s Hand,” a box containing an image of a hand, with banknotes and coins at the bottom, is a blunt critique of Pop Art and its commercial success.

Brecht's "The Hands of Lichtenstein"

In addition to numerous Western artists, this exhibition features representative works by Huang Yongping, the "founder of Xiamen Dada," as well as leading Chinese conceptual artists Geng Jianyi, Yin Xiuzhen, and Shi Yong. Together, they explore the resonance and legacy of the Fluxus spirit within the context of contemporary Chinese development. This demonstrates that the inclusion of Chinese artists not only enriches the narrative of Fluxus but also demonstrates the unique position of Chinese contemporary art within the global avant-garde spectrum. (The Paper will elaborate on this in an exclusive interview with the curator.)

At the exhibition, Geng Jianyi's work is on the left.

For this exhibition with few works on easels, the curator also wants to remind Chinese audiences that art is not just painting or sculpture, but is essentially a spiritual existence.

Note: The exhibition will run until February 22, 2026; during the exhibition period, many public projects related to unconventional art forms such as "event scores", behavioral interactions, and games will be launched.