The renowned painter Zhang Ding (1917-2010) was from Northeast China, but he preferred to associate with painters from the South, such as Zhang Guangyu, Zhang Zhengyu, Li Keran, Ye Qianyu, Li Luogong, Wu Guanzhong, Ding Cong, Huang Yongyu, Liao Bingxiong, Lu Yanshao, and Lin Fengmian. However, there were exceptions, such as Han Yu, who was from Baoding, Hebei.

This brings to mind the saying "Northerner with Southern features." Lu Xun once analyzed this psychological structure of facial features, praising its complementary strengths—"substantial yet clever." In Zhang Ding's circle of art friends, Zhang and Han were a unique pair: both Northerners, they mingled with Southern painters, and both possessed an artistic style that was "skillful yet seemingly clumsy," making them exemplary models of "Northerner with Southern features."

Han Yu was fourteen years younger than Zhang Ding. Born in 1931, the year of the September 18 Incident, Zhang Ding, unwilling to be a subjugated person, left his hometown in the spring of the following year (1932) to join the anti-Japanese national salvation movement. Although their life experiences were different, their passion for art was the same.

When did Zhang Ding and Han Yu become acquainted? The author has not verified this, but it is speculated to be sometime in the 1950s or 60s. At that time, Han Yu was in Baoding, but his heart was in Beijing. He would travel there whenever he had the chance to seek guidance from his teachers. His artistic talent quickly gained the favor of many painters in Beijing, making him a frequent guest of theirs. In 1962, Han Yu illustrated the children's collection *The Dragon on the Street* by Shanghai writer Ren Daxing. Upon its publication, it immediately attracted the attention of Zhang Ding, then the first vice president of the Central Academy of Arts and Crafts. Zhang Ding later recalled: “This was a popular book. I put it on my rare book shelf, and occasionally I would take it down and flip through it. Each time, it was a fresh experience, like listening to a child tell a story—I liked it, and my children liked it too…” (Zhang Ding, “Han Yu’s Paintings,” *Taoshan Wencun*, p. 97, Hebei Education Press, 2005).

Everyone in the art world knows that Zhang Ding is a lover of talent, sometimes to the point of obsession. His fondness for Han Yu is not surprising, but a closer analysis reveals a deeper reason. Han Yu is exceptionally gifted, loves reading, is well-versed in various fields, possesses a keen eye for art, and paints spontaneously. Furthermore, he is of a simple and innocent nature, content with his humble life, indifferent to fame and fortune, unaffiliated with factions or official positions, and his painting style is almost divine. All of these qualities deeply resonated with Zhang Ding, who was constantly burdened by the mundane affairs of the "dean" and yearned to be an "amateur painter."

Zhang Ding's letter to Han Yu dated March 28, 1977

Later, the Cultural Revolution broke out, and everyone in the arts and literature circles felt insecure, ceasing all contact. Zhang Ding and Han Yu were no exception. In early 1974, Zhang Ding ended his three-year labor camp and returned to Beijing. To escape the bustling city life, he found two abandoned farmhouses near Cherry Valley in Fragrant Hills on the outskirts of Beijing that summer and began a reclusive life, using painting to recuperate. One late autumn day, an uninvited guest suddenly arrived. His imposing attire gave Zhang Ding a fright. His wife, Chen Buwen, wrote in her diary that day:

At noon, while I was taking a nap, someone pushed open the door and entered, followed by a young man in military uniform. Bai (Zhang Ding) looked directly at him and asked, "I don't remember your surname..." The man just smiled and shook hands, then suddenly Bai said to me, "Han Yu..." I quickly laughed and said, "I'm nearsighted, how could I be so confused when we're so familiar..." How lamentable! This man was extremely sincere and genuine, one of Bai's most cherished people, yet he said he didn't remember. It must have made Han Yu unhappy, and the young man must have been quite surprised. But all that is in the past. We were truly persecutors, because seeing Han Yu in his cadre-fabricated uniform and the young man in his military uniform, we couldn't help but feel intimidated. (October 30, 1974)

Zhang Ding's cartoon "Sun Wukong Jumps Out of Laozi's Furnace," created in 1978.

This diary entry is truly poignant. Since 1966, Zhang Ding has endured the stigma of being a "traitor" and a "gangster," becoming a deeply fearful and easily frightened individual. Now, he seeks refuge in Xiangshan Cherry Valley, a place of scenic beauty but far from a paradise. The loudspeakers on the roof still blare their jarring, incessant noise every day. Now, his long-lost friend and fellow painter, Han Yu, usually unkempt and disheveled, suddenly appears, dressed in a cadre's uniform and accompanied by a young man in military attire. Zhang Ding is overwhelmed with a mixture of surprise and indescribable emotion. In Han Yu's words, it was a mixture of "surprise, joy, certainty, and bewilderment—a bittersweet experience." (Han Yu, "Remembering Tangzhuang," *Han Yu's Paintings*, p. 348, Cultural and Art Publishing House, 2008). According to Han Yu himself, at that time, he had just finished his labor reform and returned to Baoding from Tangzhuang, Xingtai. Due to his "backward" political performance, he was among the last to be allowed to return to the city and was unemployed at the time. What intrigues me is: was Han Yu's unusual visit to the reclusive Zhang Ding motivated by some special consideration? What did the two old friends discuss after their long separation? Unfortunately, there's no record of it in their diaries. However, the phrase "This person is extremely sincere and genuine, one of the people I cherish most" clearly reveals the mutual respect and affection between Zhang and Han. Everything is left unsaid.

In the years that followed, until Zhang Ding was officially rehabilitated and reinstated, was the period of closest interaction between Zhang and Han. The reason was simple: they both had free time, shared similar feelings, and had similar interests. Among them, the autumn of October 1976 was the most unforgettable. As Chen Buwen recalled: "The celebratory parade was as surging as a tide, with slogans, songs, gongs, drums, and firecrackers going on day and night. Zhang Ding was also extremely excited. One day, he turned around from the window and said: 'I'm going to draw cartoons. The Gang of Four is an excellent subject for cartoons.'" (Chen Buwen, "The Evolution of Zhang Ding's Cartoon Creation," *Zhang Ding's Cartoons*, p. 120, Liaoning Fine Arts Publishing House, 1985)

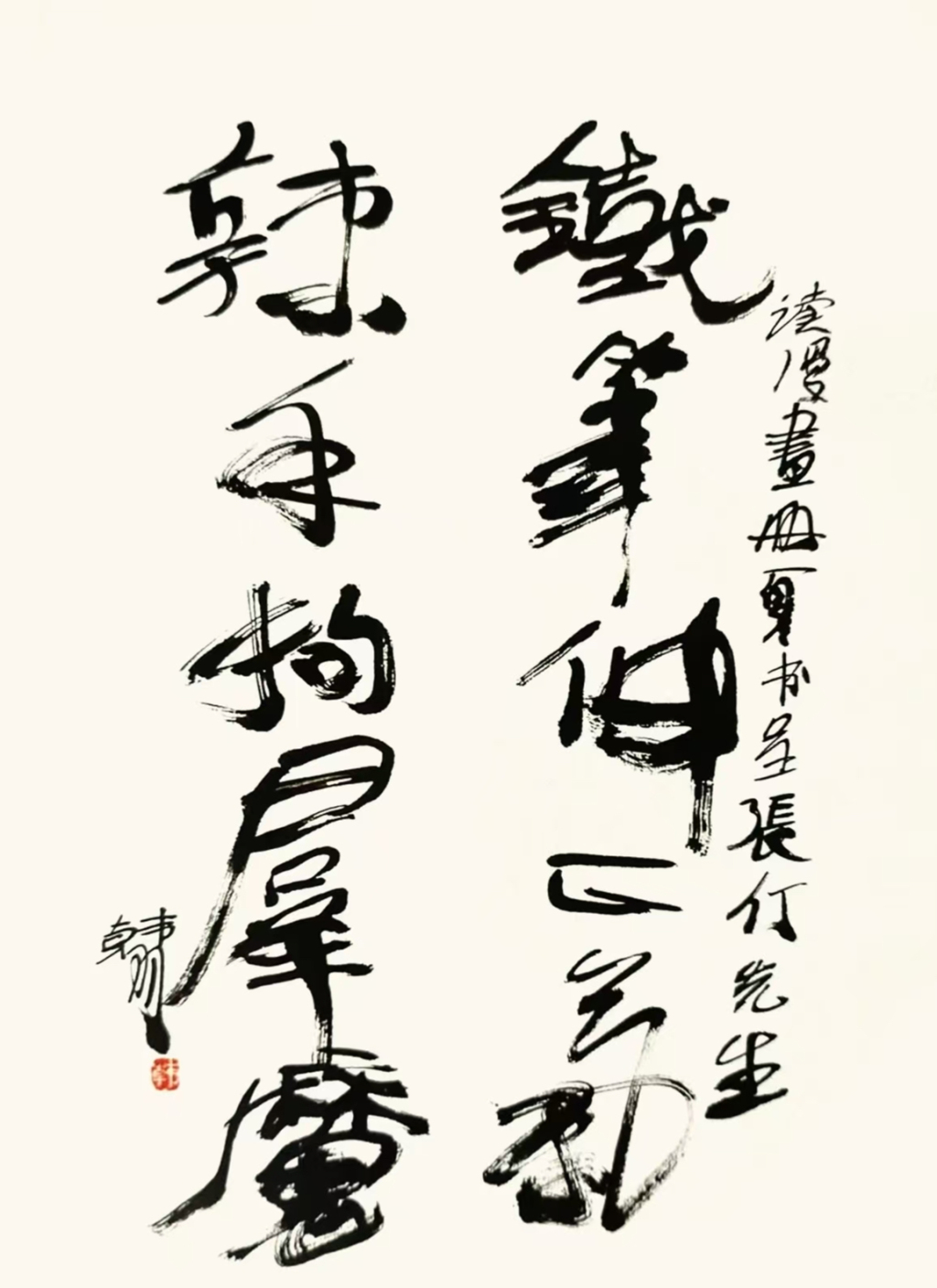

So Zhang Ding abandoned his ongoing exploration of ink wash landscape painting and began drawing cartoons, a task he hadn't done for twenty years. Soon, a series of cartoons titled "Let This Be a Record," satirizing the "Gang of Four," was published. Its profound thought and superb technique made it shine, standing out among the countless cartoons of the same subject. Han Yu witnessed this entire process firsthand, and even participated in it. Consider his inscription for the cartoon book: "With an iron pen, righteousness prevails; with a ruthless hand, demons are subdued." His brushstrokes are vigorous, unconventional, and unrestrained.

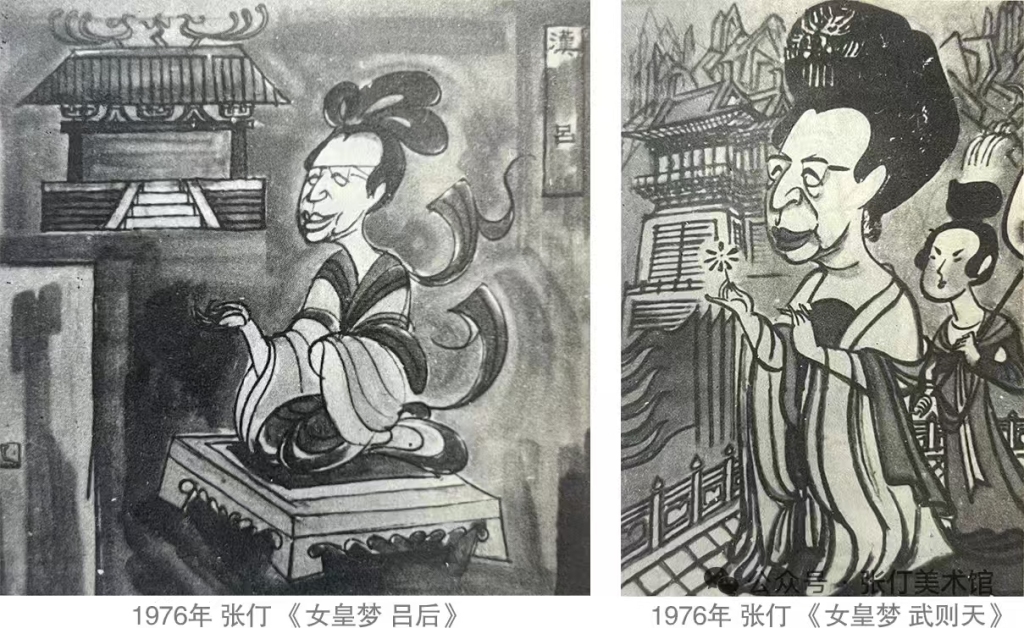

Years later, Han Yu recalled: “Every time I flip through Zhang Ding’s paintings, when I come to the cartoon ‘Empress’s Dream,’ memories flood back. When Mr. Zhang Ding was creating ‘Empress’s Dream,’ I often went to his house, stood by his side, and watched him wield his brush. Whenever he encountered a discarded draft, he would put it into his pocket, accumulating little by little until it became a complete masterpiece. I would often feel secretly pleased with myself, proudly saying: Who has the first draft of ‘Empress’s Dream’? I have it.” (Han Yu, “Zhang Ding’s Letters,” *Notes on Reading Letters*, p. 164, published by Shanxi Publishing Media Group·Beiyue Literature and Art Publishing House, 2015) – his pride was palpable. This pride was natural and well-deserved. As a kindred spirit of Zhang Ding, Han Yu's understanding of this series of comics possesses a depth and professional precision that is unparalleled. Consider his commentary on "Empress's Dream: Empress Lü": "The lines, colors, clothing, and furnishings are remarkably similar to unearthed Han Dynasty tomb murals (omitted). It transcends time and space, creating a hazy, dreamlike atmosphere. It is precisely this absurdity that allows it to touch upon the most authentic reality. The colors are particularly exquisite; the mottled, peeling effect created by the application of red, yellow, and blue evokes synesthesia, allowing the viewer to perceive the form and smell the damp, musty odor of an old tomb." (Source: same as above) This is truly insightful.

Left: Zhang Ding's comic book "Empress's Dream: Empress Lü" Right: Zhang Ding's comic book "Empress's Dream: Wu Zetian"

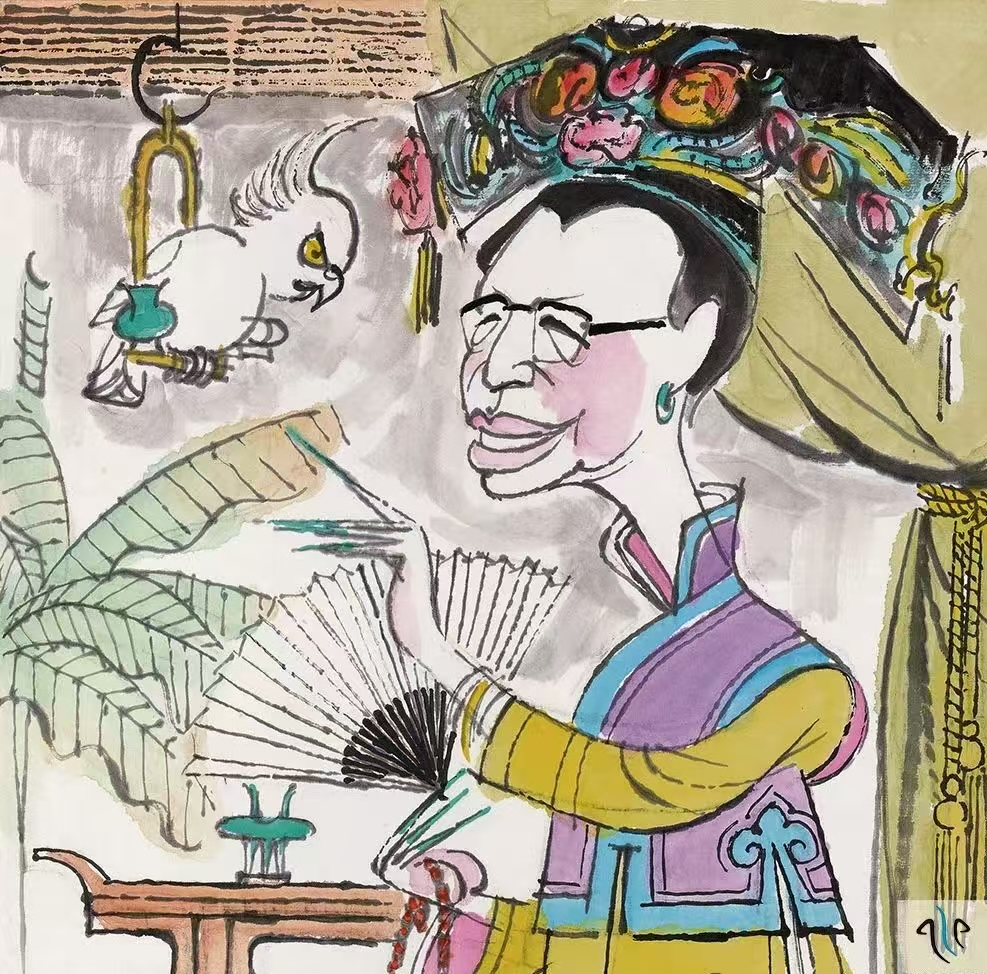

Zhang Ding's comic strip "Empress's Dream: The Empress Dowager" was created in the winter of 1976.

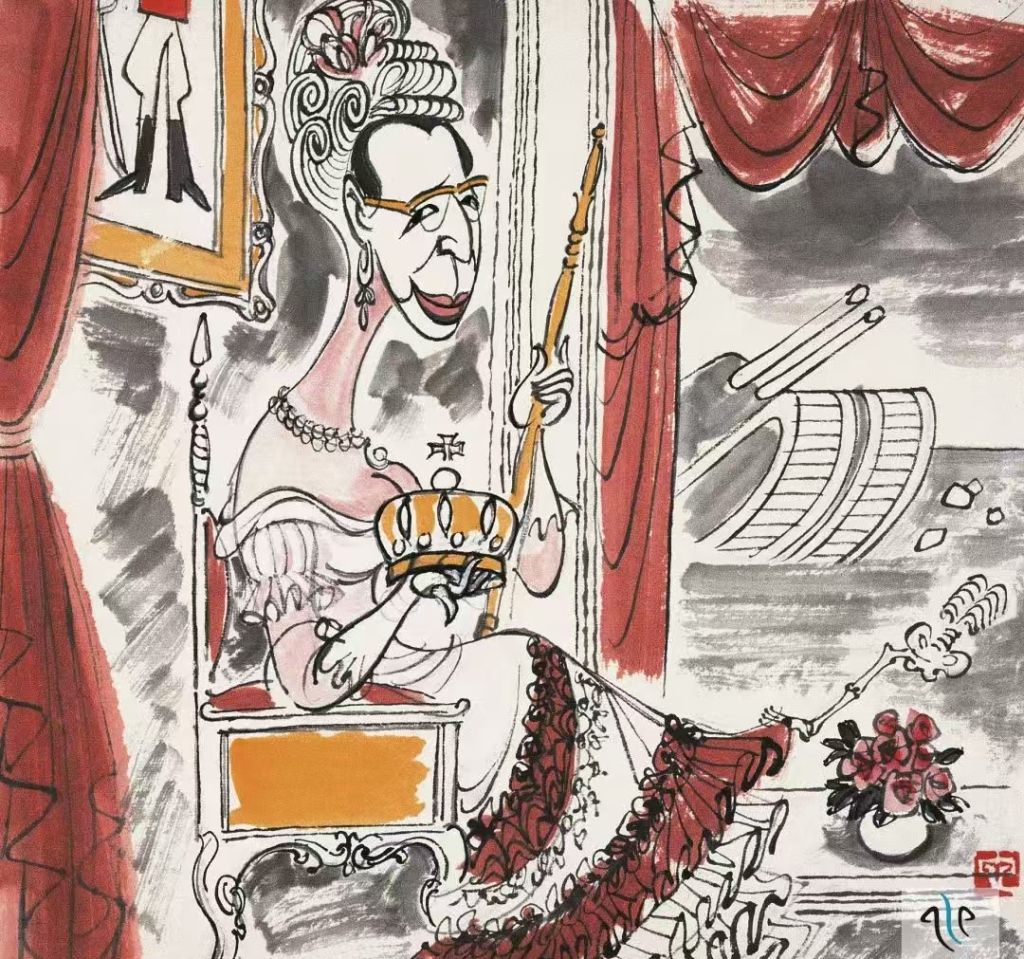

Zhang Ding's comic strip "Empress's Dream: Catherine" was created in the winter of 1976.

Han Yu wrote the inscription for Zhang Ding's cartoon series "Preserving This as a Preservation," in 1977.

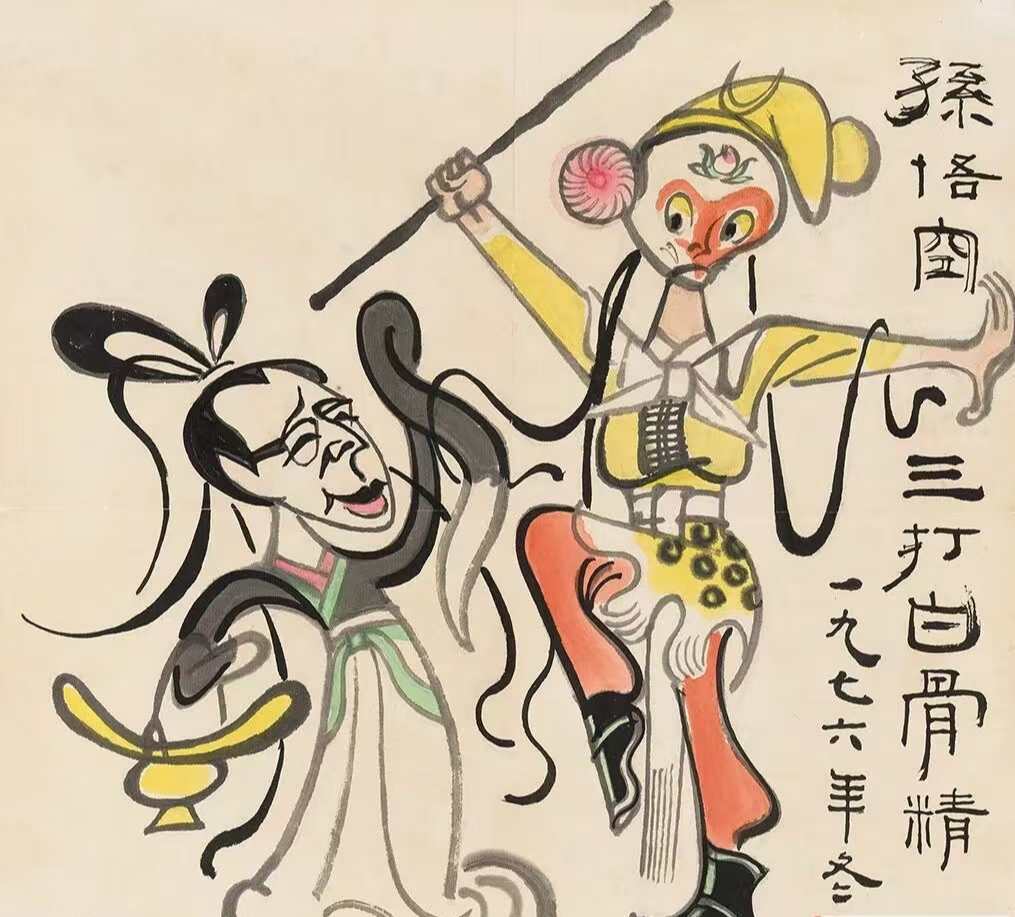

One of Zhang Ding's cartoons, "Sun Wukong Thrice Beats the White Bone Demon," created in the winter of 1976.

This series of cartoons includes two panels titled "Sun Wukong Thrice Beats the White Bone Demon." Interestingly, two years earlier, during the height of the "black art" controversy, Han Yu, in an attempt to avoid the omnipresent criticism of Mao Zedong, also created a Chinese painting depicting the imagery of Chairman Mao's poem, "The Golden Monkey Wields His Mighty Cudgel." Unexpectedly, two years later, the theme of this painting suddenly acquired a different symbolic meaning and became immensely popular. Zhang Ding's two cartoons, "Sun Wukong Thrice Beats the White Bone Demon," each possess artistic ingenuity, forming an interesting contrast: one depicts Sun Wukong, wielding his golden cudgel, staring intently at the disguised White Bone Demon, who carries a flower basket and dances with flowing sleeves, preparing to deliver a precise blow; the other shows the White Bone Demon, disguised as a black-headed leopard, battling Sun Wukong. Now revealed in her true form, with disheveled hair, bare chest and back, wearing large sunglasses, and wielding a trident, she lunges at Sun Wukong with bared teeth and claws. Sun Wukong, however, displays utter contempt, even sheathing his golden cudgel, closing his eyes to rest, before lightly throwing a punch that strikes the White Bone Demon's vitals. Zhang Ding only sent Han Yu the first cartoon, refusing to send the second. The reason for this refusal is clearly stated in a letter to Han Yu dated March 28, 1977—

Comrade Han Yu:

Your inscription for the comic book is very tasteful, thank you.

I'm sending you two pages of cartoons for your critique. The other one uses the same composition as before. Because I think the one depicting a cross-dressing leopard is slightly suggestive, I don't want to copy it and send it to friends—since the struggle against the "Gang of Four" is a serious one. Do you agree? (Source: same as above)

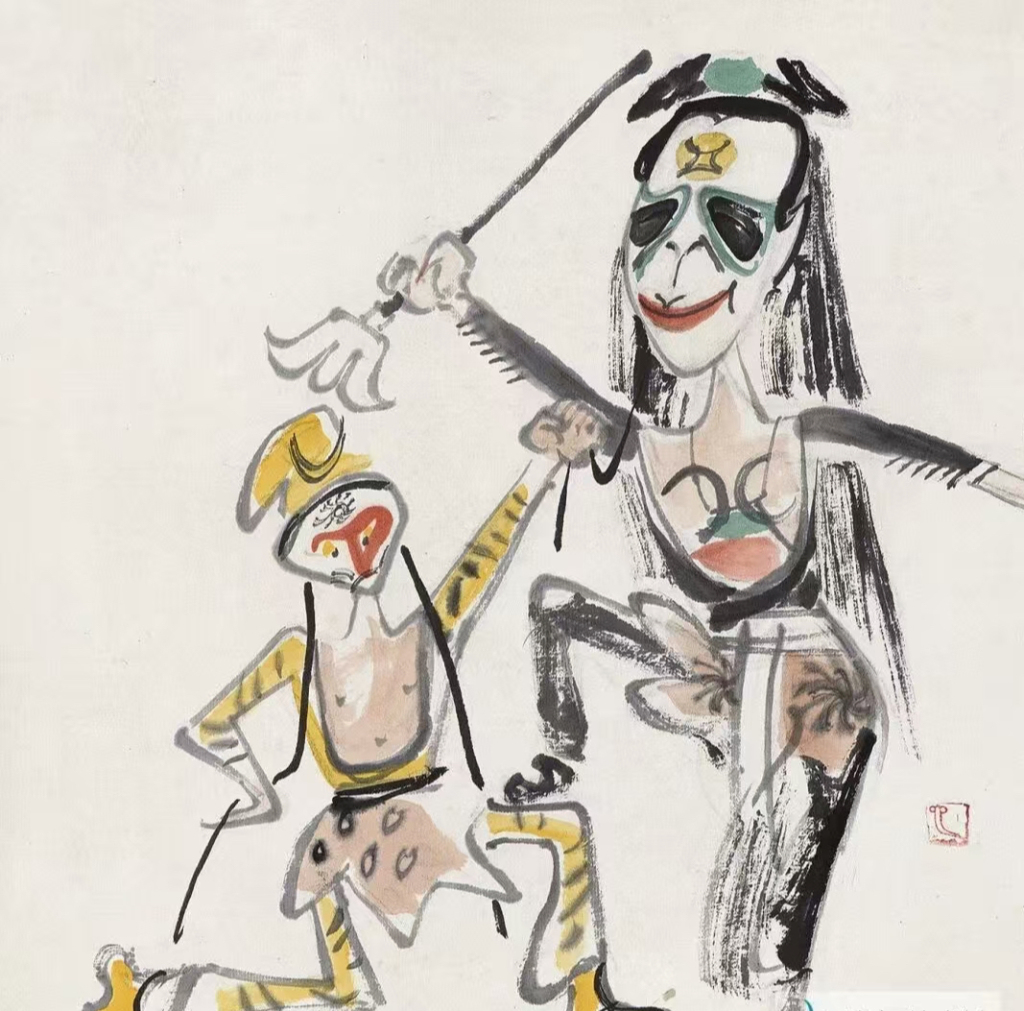

Zhang Ding's second comic strip, "Sun Wukong Thrice Beats the White Bone Demon," was created in the winter of 1976.

This letter is truly poignant. Zhang Ding considered the latter painting, "Sun Wukong Thrice Beats the White Bone Demon," to be "slightly pornographic," even elevating it to the level of a "serious struggle" criticizing the "Gang of Four," effectively politically rejecting the painting. Upon close examination, however, one cannot discern any "pornography"—not in the erotic sense, but at most a bit too playful and not "serious" enough. After much contemplation, it suddenly occurred to me: does this reflect a unique contradiction within Zhang Ding? That is to say, as a painter and artist, Zhang Ding is free-spirited, open, and fearless; as the leader and president of the Central Academy of Arts and Crafts, Zhang Ding is self-disciplined and obedient.

Zhang Ding was a "great artist" shaped by his era. For decades, amidst the contradictions and tensions between art and politics, painter and dean, revolutionary work and personal interests, he navigated these challenges, adapting and coordinating to achieve remarkable and groundbreaking artistic accomplishments, thus becoming a unique "overpass" in the history of art in New China. Han Yu has a unique understanding of this, writing in his article "Not Discriminating Against Soil, Not Choosing Small Streams":

Although Mr. Zhang Ding did not look like a farmer at all (he told me more than once that he was a farmer), he had the same good appetite as a farmer.

Farmers have an insatiable appetite, accepting and absorbing everything regardless of whether it's raw, cold, soft, hard, sour, sweet, bitter, or spicy. They can even melt a piece of cast iron. And their appetites are so enormous that they command respect. They can eat five cornbread buns in one meal, along with five large bowls of porridge. "To see if someone is capable, first see if they can eat." It is precisely because of this that they have developed strong bodies and muscles, able to put down the pitchfork, pick up a broom, and do everything from hoeing to plowing and harrowing.

Mr. Zhang Ding's voracious appetite, like that of a farmer, is specifically designed for art. Whether traditional or modern, ancient or contemporary, he takes it all and digests it all. Even poisonous weeds can be transformed into medicine; even dross can be extracted to obtain its essence. It is precisely this broad and eclectic approach that makes Mr. Zhang Ding's art so extraordinary and exquisite, encompassing numerous fields: traditional Chinese painting, cartoons, murals, decorative paintings, propaganda posters, New Year pictures, and arts and crafts.

Whenever I look through the paintings of this senior artist, I can't help but think of his good appetite, and of Li Si's words: "Mount Tai does not reject any soil, therefore it can become so great; rivers and seas do not discriminate against small streams, therefore they can become so deep." (Han Yu's Paintings, p. 338, Cultural and Art Publishing House, 2008)

Han Yu highly praised Zhang Ding's "appetite," but in truth, his own appetite was no less impressive. Otherwise, how could he have achieved such remarkable success in so many fields, including poetry, calligraphy, comic illustration, film animation, and opera figure painting? However, I believe Han Yu's "appetite" is more evident in his literary pursuits. His extensive reading, his classical scholarship, and especially his ability to "retell stories" are unmatched by many contemporary artists. Zhang and Han's different "appetites" have yielded different artistic results. If Zhang Ding's sketches are inspired by nature, his paintings are imbued with emotion, and he skillfully captures the essence of creation, then Han Yu's art is cultivated through reading, his literary mind inspires his paintings, and with just a few strokes, he encompasses the vastness of history and the present. Each has their own unique lifeblood and spirit.

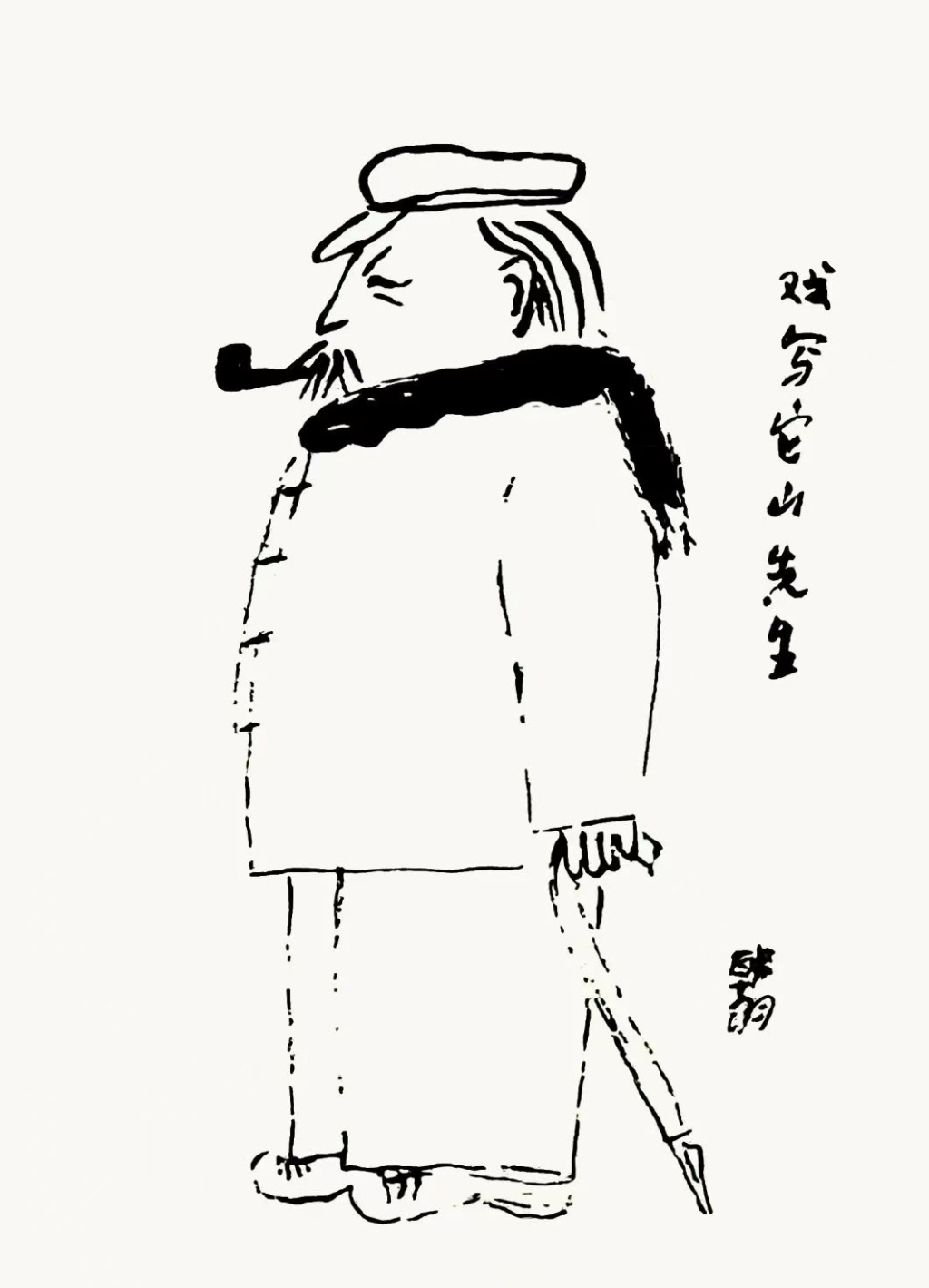

Han Yu's painting of Zhang Ding, created in the 1990s, playfully depicts Mr. Tashan.

Han Yu painted a work titled "A Playful Portrait of Mr. Tashan," which is the most expressive and exquisite portrait of Zhang Ding that I have ever seen. With simple and relaxed lines, it depicts a simple, elegant, and childlike old artist, steady and substantial yet possessing a keen intelligence. The exaggerated form "almost to the point of absurdity" (Zhang Ding's comment on Han Yu's theatrical figure paintings), yet it evokes an extraordinary sense of realism and intimacy—a quality that is essential. The expression on the face clearly references Zhang Ding's self-portraits, while the vividly portrayed hat, pipe, scarf, and the wondrous cane that resonates with Zhang Ding's spirit are purely Han Yu's own creation. It is evident that Han Yu created this painting with deep emotion and tacit understanding, reflecting his own image and style.

What a wonderful pair of artists, both northerners with southern features, who appreciate each other's talents!

Han Yu's work "The Crossroads"

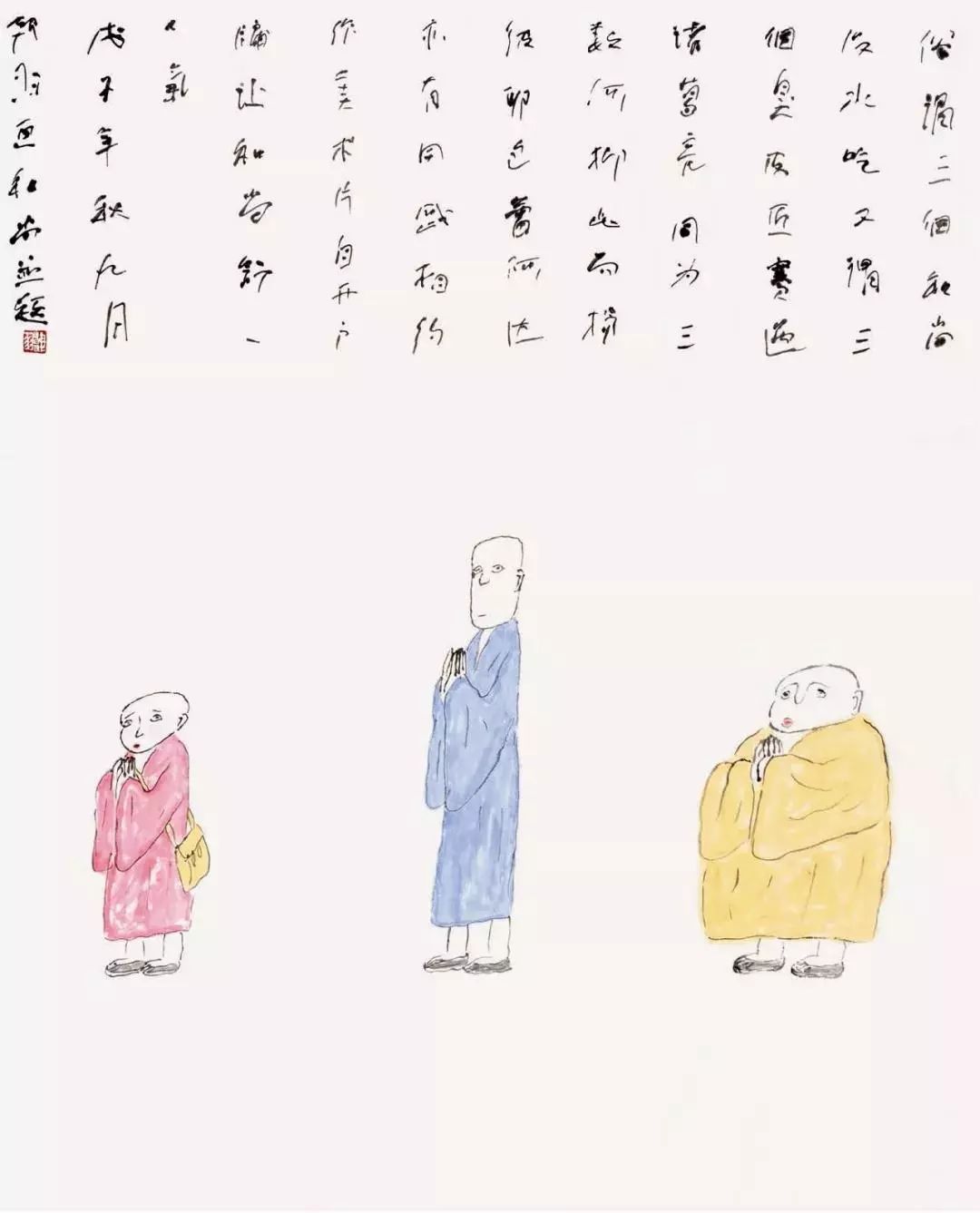

Han Yu's painting "Three Monks" is titled: "There is a saying that 'three monks have no water to drink,' and another that 'three cobblers are better than Zhuge Liang.' Both are three, so why suppress one and praise the other? Bao Lei and Ada also felt the same way and agreed to make an animated film called 'Open the Window,' so that the monks could breathe a sigh of relief."

September 7, 2025