Born in Hunan in 1932, he moved to Nanjing as a child, then to Taipei in his teens. From Paris to New York, he settled in Shanghai over two decades ago. This is the trajectory of both the 93-year-old artist Xia Yang's wanderings and his own painting: he has journeyed to the forefront of modern art, witnessed the rise of abstraction and conceptualism, and returned to Shanghai in his later years, exploring the possibilities of modern Chinese art by drawing on folk art and contemporary materials.

The "Artists in Shanghai" column of The Paper recently visited Xia Yang's studio with a pointed roof in Longbai, a western suburb of Shanghai. This is also Xia Yang's residence - he has lived and created here for 23 years since 2002.

Xia Yang, 93, wears a hand-painted hat in his studio (which also serves as his living room).

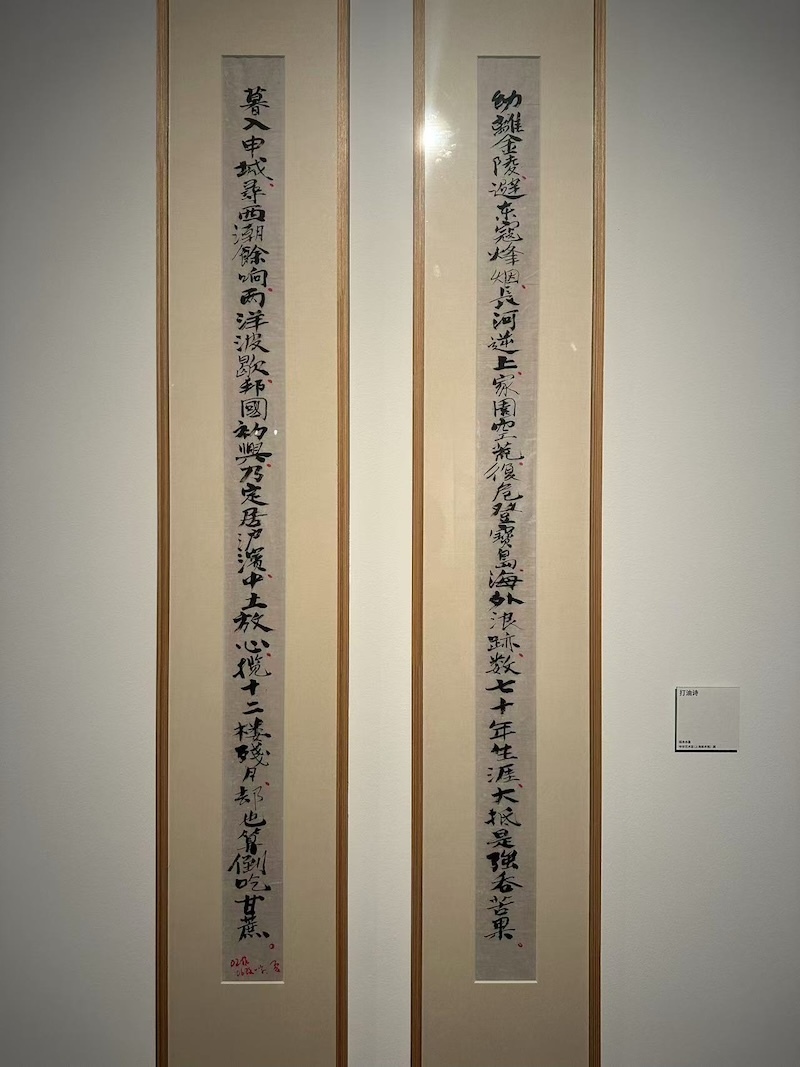

"I left Nanjing at a young age to avoid the flames of war from the Eastern invaders. The long river flows upstream, my home is deserted, and I land on the island of Treasure. My life of wandering overseas for seventy years has been mostly a bitter experience.

At dusk, I enter Shanghai, seeking the lingering echo of the western tide. The waves of the two oceans have subsided, and the nation is just beginning to rise, so I settle down on the shores of Shanghai. The Central Plains are at ease, embracing the waning moon from the twelfth floor, which is like eating sugarcane from the bottom of your heart.

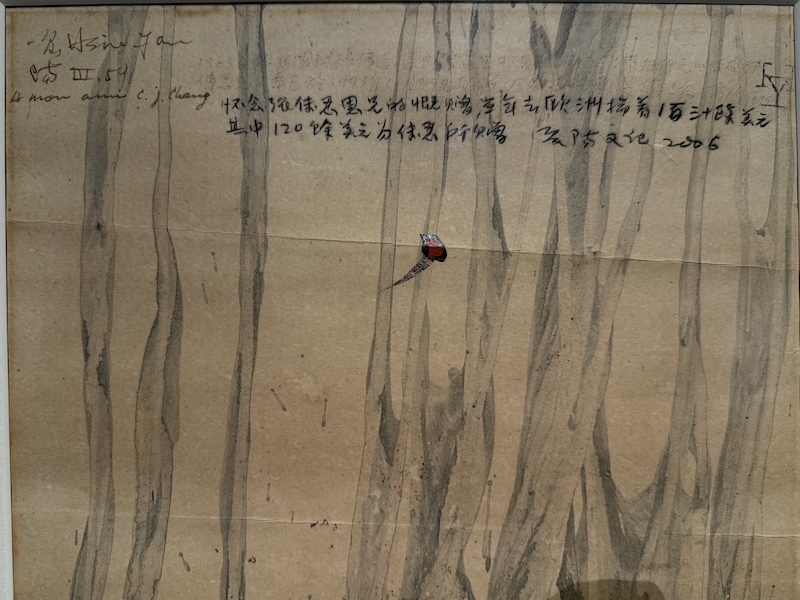

Xia Yang's "Douglas" tells his own story (written in 2002, one word changed in 2006)

This doggerel poem was written by 70-year-old Xia Yang in 2002 to recount his experiences of wandering. That same year, he bought an apartment in western Shanghai and moved there, never leaving.

2025 marks Xia Yang's 23rd year living in Shanghai. In early autumn, The Paper Art Review visited his studio, located on the top floor of an apartment building in the city.

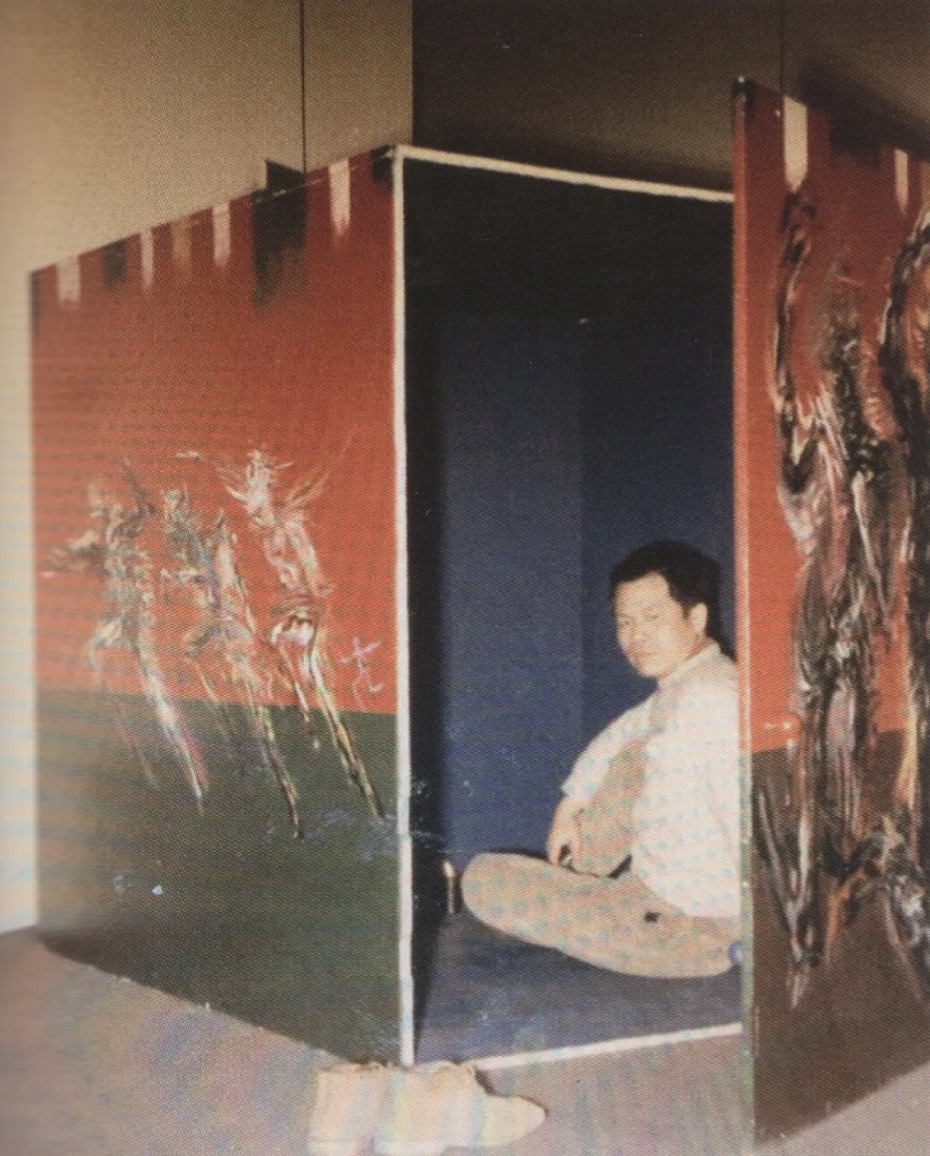

Taking the elevator to the 11th floor, then walking up to the top floor (the 12th), into the studio (or living room), 93-year-old Xia Yang beamed as he displayed his homemade "easel," resembling a stage curtain. When he pulled the cord, the canvas suddenly rose, instantly revealing how the four-meter-tall paintings donated to the museum were created. The towering ceiling of this apartment, by comparison, is estimated to be over four meters high.

Xia Yangke pulled up his homemade easel and is currently creating the story of Yang Xiang fighting a tiger to save her father.

"I don't paint every day now, except sometimes," Xia Yang quipped, describing his current state. "I rarely go out, just exercise on the balcony and water the flowers." He then took the reporter from The Paper to the balcony, where there were plants and a view of the city skyline. Two architectural components were nailed to the balcony: one was a carved wooden ox leg from a traditional Chinese dwelling, and the other was from New York's SoHo, a souvenir he picked up when he left the city. "It's the only souvenir I have related to SoHo."

There are two architectural components on the balcony, one is a wooden carved ox leg from traditional Chinese houses, and the other is from SoHo in New York.

When asked why he chose to settle in Shanghai, Xia Yang summed it up as "it was all fate" - he said that it was because housing prices in mainland China were cheaper than in Taipei at the time, and he looked for many places, but in the end he still liked Shanghai. In addition, Shanghai oil painter Yin Xiong introduced him to this apartment on the top floor with sufficient height. "I fell in love with it at first sight because of the height."

And he lived there for 23 years, from his 70s to 93 years old. "What else can I think about when I'm in my nineties? I have nothing to do, so I'll just paint some pictures," said Xia Yang.

Xia Yang said that he had not done much sketching and his basic modeling skills were relatively poor. He said that the so-called realism nowadays is completely inaccurate and should be called "imitation of realism".

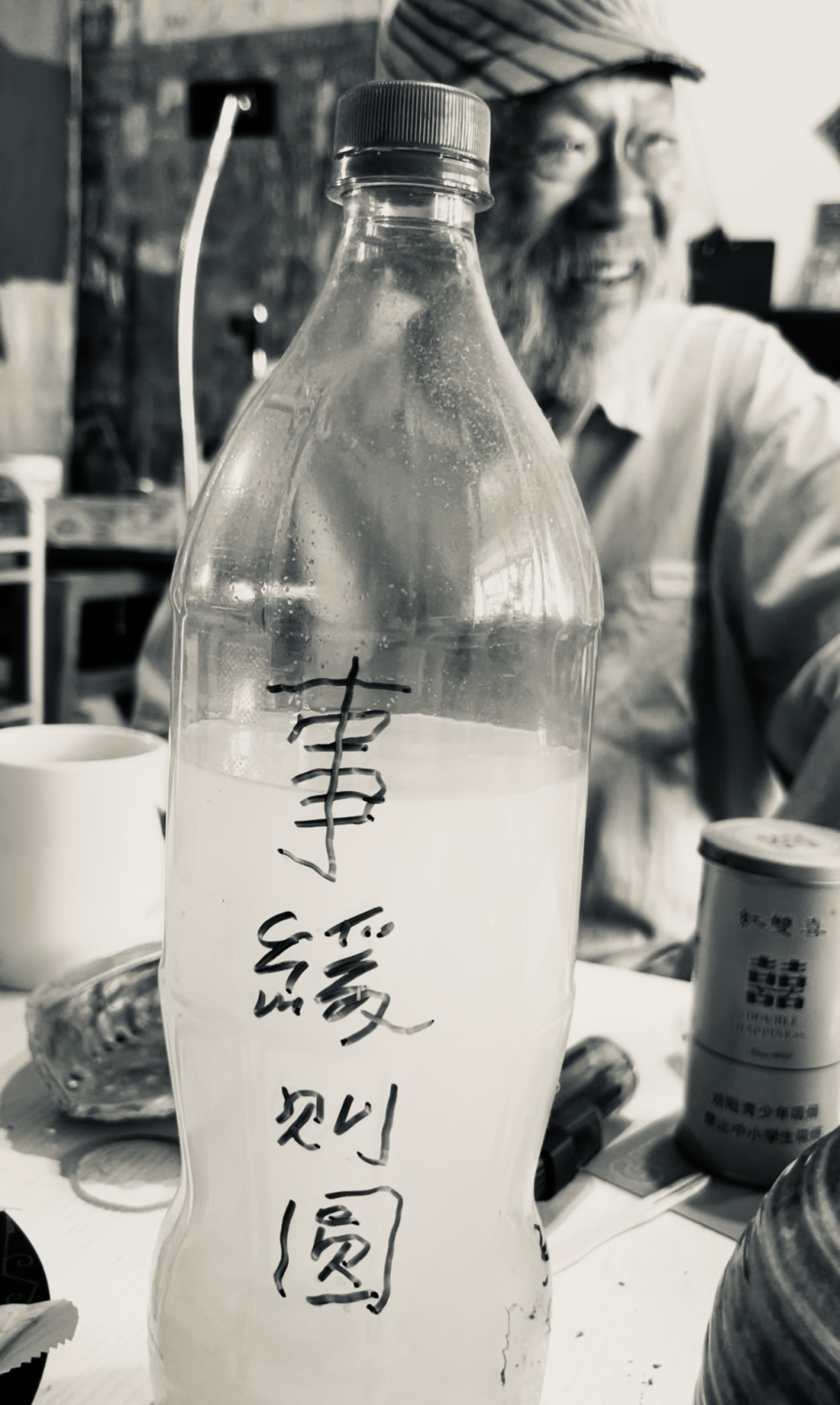

Xia Yang and the Sprite bottle that says "Slow and steady wins the race"

Talking about his recent creations, he cheerfully took out a bottle of Sprite with the four big characters “施慢才会故” written on it, which contained acrylic paint thinner. He said that “施慢才会故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故故 ...

In early 2025, the Shanghai Museum of Contemporary Art held Xia Yang’s solo exhibition “Old Trees, New Branches”, which was based on 130 contemporary art works donated by Xia Yang.

In recent years, Xia Yang has donated numerous works to various state-owned art museums. In 2025 alone, he donated 130 works (from the 1950s to the 1990s) to the Power Station of Art (PSA) in Shanghai. These works were featured in the exhibition "Old Trees, New Branches" earlier this year, allowing viewers to witness how the artist constructs his own visual language and narrative. In April, at the opening of Xia Yang's art exhibition "Only One Kind of Heroism" at the Nanjing Jinling Art Museum, he donated another 89 works to his hometown. Following several donations to the Shanghai Art Museum, Xia Yang made another significant donation with the exhibition "Where My Heart Is at Peace: Xia Yang's Artistic Journey and Home." Meanwhile, scattered casually on the desk in Xia Yang's studio are other donations.

The exhibition "Where My Heart Is at Peace: Xia Yang's Artistic Journey and Home" at the Shanghai Art Museum

From studying painting with Mr. Li Zhongsheng in the 1950s, to leaving for Paris and New York in the 1960s, to moving to Taipei, China in 1992 and settling in Shanghai in 2002... From lines, to mystical abstract painting techniques combined with written characters, to "hairy people", and then to creations incorporating folk art... each piece of work tells the story of his ups and downs in the sea of people.

Basic skills are constraints, Li Zhongsheng is the spark

"'Realism' is not an doctrine, but a technique. China has freehand brushwork, realistic painting, and sketching from life. Adding 'realism' won't work. It can only be called 'faux realism'—imitation of reality."

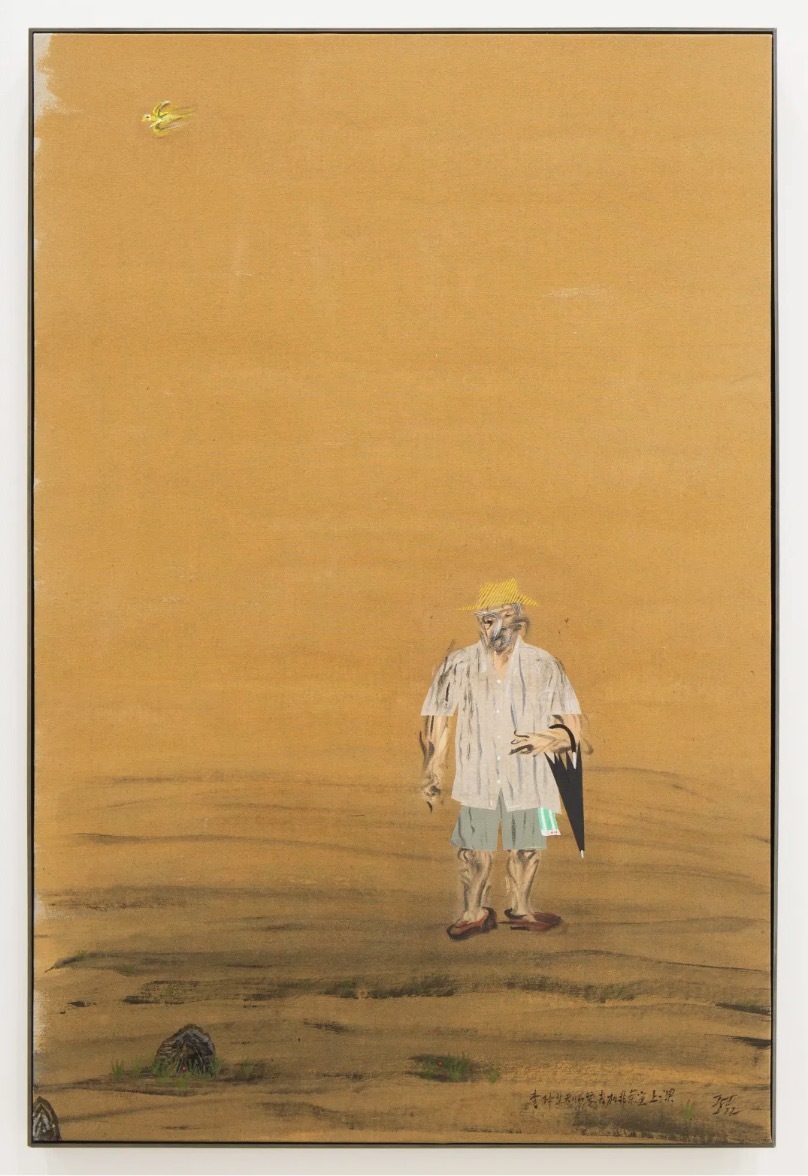

Xia Yang, “Teacher Li Zhongsheng is going to teach in a cafe,” 2022, acrylic on canvas, paper cutouts

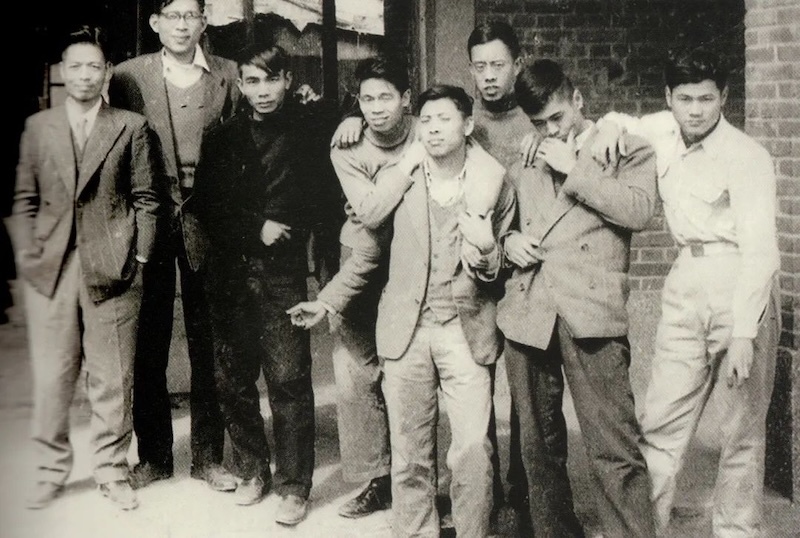

When discussing his artistic journey, Xia Yang first mentions his teacher, Li Zhongsheng (1912-1984). Li Zhongsheng was the youngest member of the Juelan Society (a modern art group founded in Shanghai in 1932 and disbanded in 1935), and a pioneer of abstract art in Taiwan. He studied Western modern art in Japan under Foujita Tsuguharu. His classmate, Kim Hwan-ki, was the father of modern Korean painting. However, Li Zhongsheng faced financial hardship in Taiwan, earning a living by teaching painting. This led Xia Yang to study painting with Li Zhongsheng at the Andong Street Art Studio in Taipei.

From left: Li Zhongsheng, Chen Daoming, Li Yuanjia, Xia Yang, Huo Gang, Wu Hao, Xiao Qin, and Xiao Mingxian in Yuanlin, 1956. Courtesy of the artist.

It was 1951. At the time, the mainstream art education in both mainland China and Taiwan was conservative, academic, and solid foundational skills in sketching were essential for the path to art. In Li Zhongsheng's studio, while he also painted plaster figures, he opposed basic skills, believing they would restrict creativity. More often, Li Zhongsheng focused on line and movement, as well as the concepts of modern art. "When he was chatting, he'd often say, 'Realism lacks figuration, and figuration lacks realism,'" Xia Yang recalled. "He'd also talk about Foujita. We sketched, worked with lines, and experimented." "That was our education. We pursued modernism because Li Zhongsheng taught us that, and we inherited that perspective." It was also thanks to Li Zhongsheng that "our minds opened up."

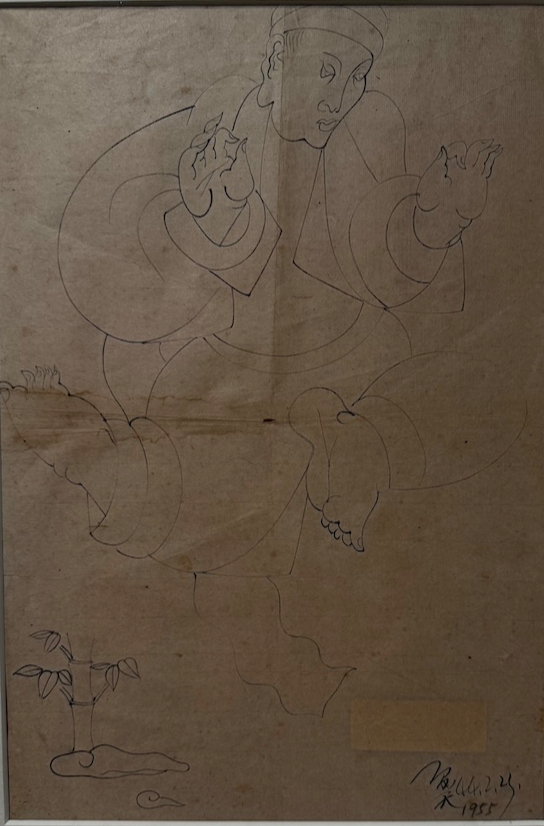

Xia Yang's line drawing in 1955.

Having traveled extensively around the world and visited the forefront of Western contemporary art, Xia Yang is more in tune with Li Zhongsheng's perspective. "Basic skills are the training of a craftsman. In the West, there's no distinction between artisan painting and literati painting; apprenticeships are designed to enable them to paint. Therefore, with the invention of the camera, Western art overturned these basic skills and began to modernize."

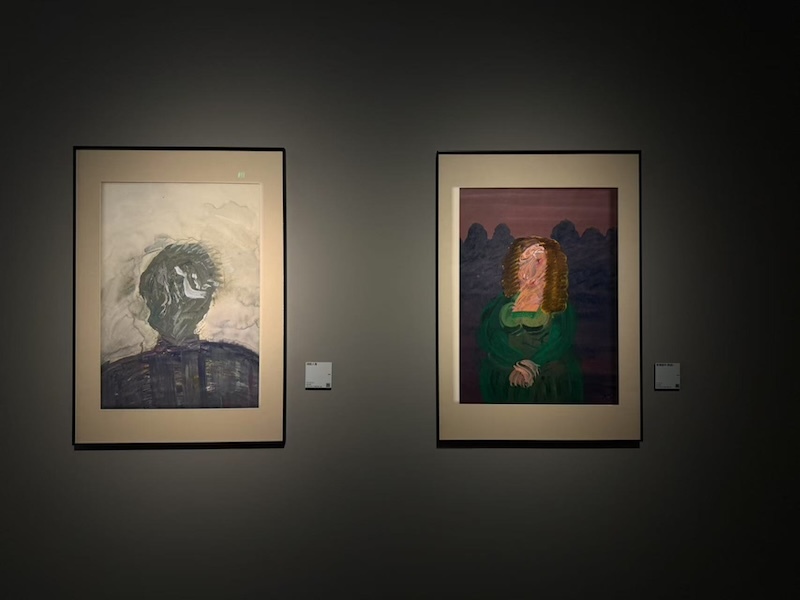

The Shanghai Art Museum's "Where My Heart Is at Peace: Xia Yang's Artistic Journey and Home" exhibition, with "Green-Faced Portrait" on the left and "Mona Lisa (Pink Face)" on the right.

When he moved from Paris to New York in 1968, he found virtually no traditional "painting" there. Instead, it was dominated by conceptual art, installations, and photographic collages. Only "photorealism" was still hand-painted, so he created a series of "photorealist" works. However, he disagreed with the term "realism," believing it to be merely a technique. "It can only be called imitation—imitation of reality. China already has freehand painting, photorealism, and sketching. Adding realism wouldn't work, and there's no way to even talk about 'realism'."

Among them, "Mr. Kapp in the Office: The Chinese Painter's Best Friend," donated to the Shanghai Art Museum, is a unique example within the "Photorealism" series. The subject, an American gallerist active in Sino-US artistic exchange in the late 1980s, is difficult to identify due to motion blur. Behind him is an abstract painting composed of dripping paint and streaks. On the foreground table is a reclining classical female sculpture, with a plaque on the tabletop further hinting at the subject's identity. Although a portrait, this work departs from traditional documentary logic. The "photographic delay" technique renders the subject difficult to identify, becoming a symbol of a "systemic role."

Xia Yang, “Mr. Kapp in the Office: The Best Friend of Chinese Painters,” late 1980s, oil on canvas

"The first picture I painted was of the gallery owner because he is very famous. Although the person is not clear, you can tell who it is from the background. But I can't find a second one, so this is the only one in this series." Xia Yang recalled that this was also his last large-scale photorealism work before he returned to creating "Hairy Man".

In his paintings, there's no emphasis on fundamentals, nor is there deliberate showmanship. Xia Yang meticulously handles figures, still lifes, and materials with each stroke. "Sketching requires immersion and meticulous work to achieve flavor. But this flavor is often invisible."

Xia Yang, "Urban Bird"

After a lifetime of wandering, he settled in Shanghai at the age of 70.

"We've had a hard time since we were little, so we've gotten used to it."

Born in Hunan in 1932, Xia Yang returned to his hometown of Nanjing with his grandmother at the age of two. Though he came from a family of scholars, his parents died young. At five, he fled the war, traveling from Nanjing to Wuhu, then to Hankou, and from Hankou to Sichuan, returning to Nanjing in poverty by wooden boat. Because normal school was free and offered subsidies, he attended Nanjing Municipal Normal School for secondary school. When his teacher gave him paper to draw on, he would pin a small notebook and draw endlessly.

In 1949, he joined the army in Taiwan, China, where he lived with his uncle He Fan (Xia Chengying) and his aunt Lin Haiyin. He later studied painting with Li Zhongsheng, and in 1955, he organized the "Oriental Painting Exhibition" (Oriental Painting Society) with Xiao Qin and others. In 1963, he embarked on a solo ship to Europe, first arriving in Marseilles and then taking a train to Milan. "In Milan, I discussed it with Xiao Qin. He said that going to Paris would be difficult, but that fame there was world-class, while in Italy, it was local. He was actually talking nonsense. I said, okay, I went, and it was hard, so I went."

In 1963, Xia Yang was about to embark on a trip to Europe. Before leaving, his aunt Lin Haiyin (1st from right), uncle Xia Chengying (He Fan) (1st from left), and relatives and friends came to see him off.

In Paris, Xia Yang lived in the attic of a hotel owned by a Vietnamese Chinese expatriate and worked for him. "I did everything, from taking out the trash to fixing electrical wires. The most dangerous thing was climbing up the roof to do it," Xia Yang described, gesturing. "I had to carry tar and a stove, climbing the slope from the seventh floor roof to the next roof. Any moment of panic would have made me fall. I was completely lost, covered in paint, and I felt very proud, not at all miserable."

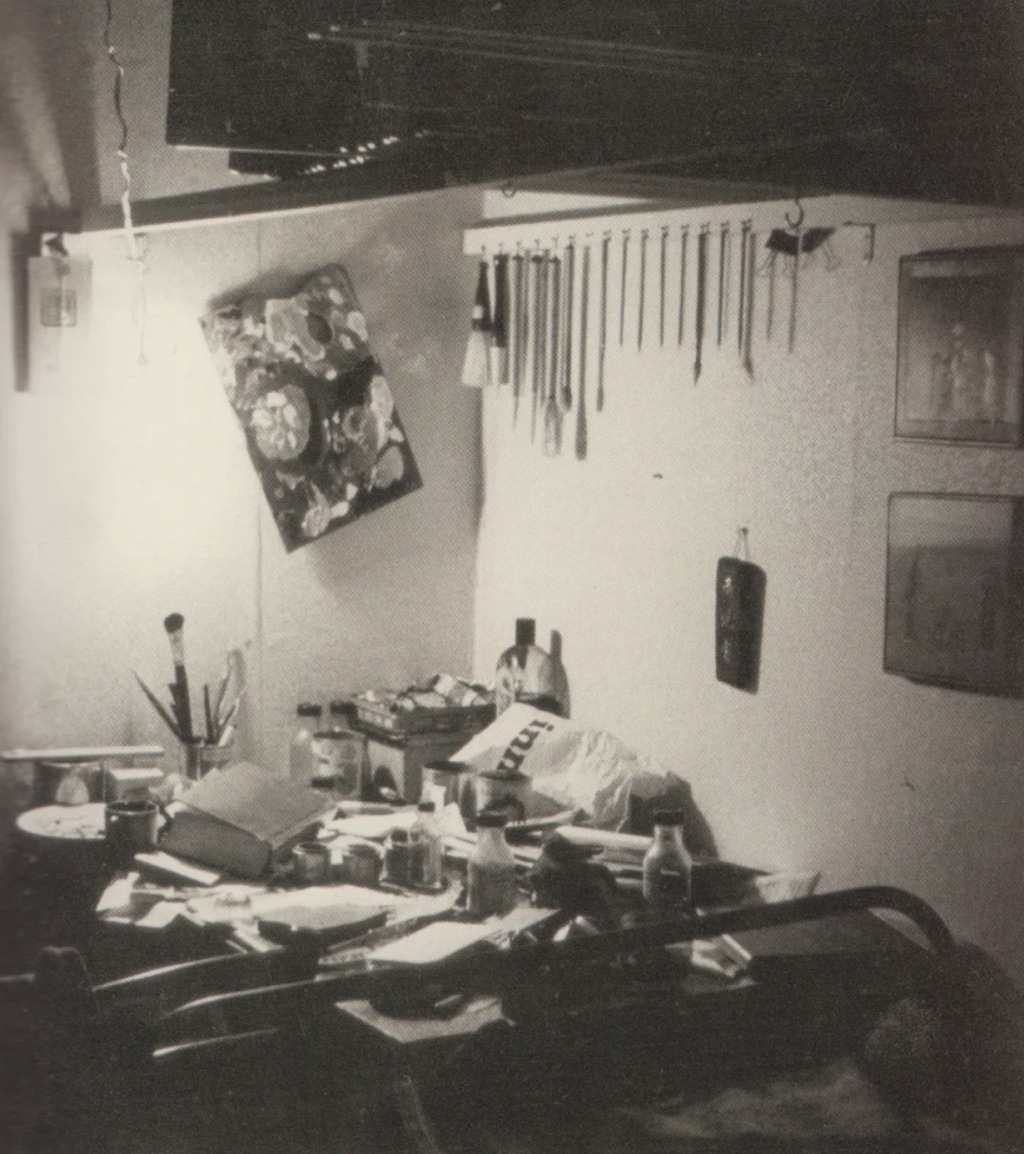

A corner of Chayang's studio in Paris in the 1960s.

Xia Yang developed the "Hairy Man" series in Paris.

Xia Yang’s “Hairy Man” series originated from his correspondence discussions about art with Xiao Qin. Unable to afford to send photographs, he could only understand the trends of Western modern art through Xiao Qin’s tiny handwriting on postal paper, and “paint according to his imagination.” Later, “Monochromism emerged, and I also drew many thin lines and many symbolic things based on his words.” After arriving in Paris, Xia Yang further experimented with mixing thick and thin lines, abstract and concrete, to create figures that are both symbolic and abstract. This uncertainty seems to concretize wandering and loneliness, blurred identity and absurdity.

Xia Yang, “Forest” (earliest abstract painting from the Paris period), 1964, acrylic and watercolor on canvas

In one of Xia Yang's works, it says "Go to Europe with $130"

Because life in Paris was too hard, two friends moved to New York, where life was "much better." "Because of the word 'much better,' we all went to the United States. At that time, America was also the contemporary era." As mentioned above, Xia Yang focused on creating out-of-focus figures and hyper-realistic street scenes in the United States. However, he was one of the few Chinese artists who directly participated in New York's flourishing period as a global art center after World War II, from the 1960s to the 1970s.

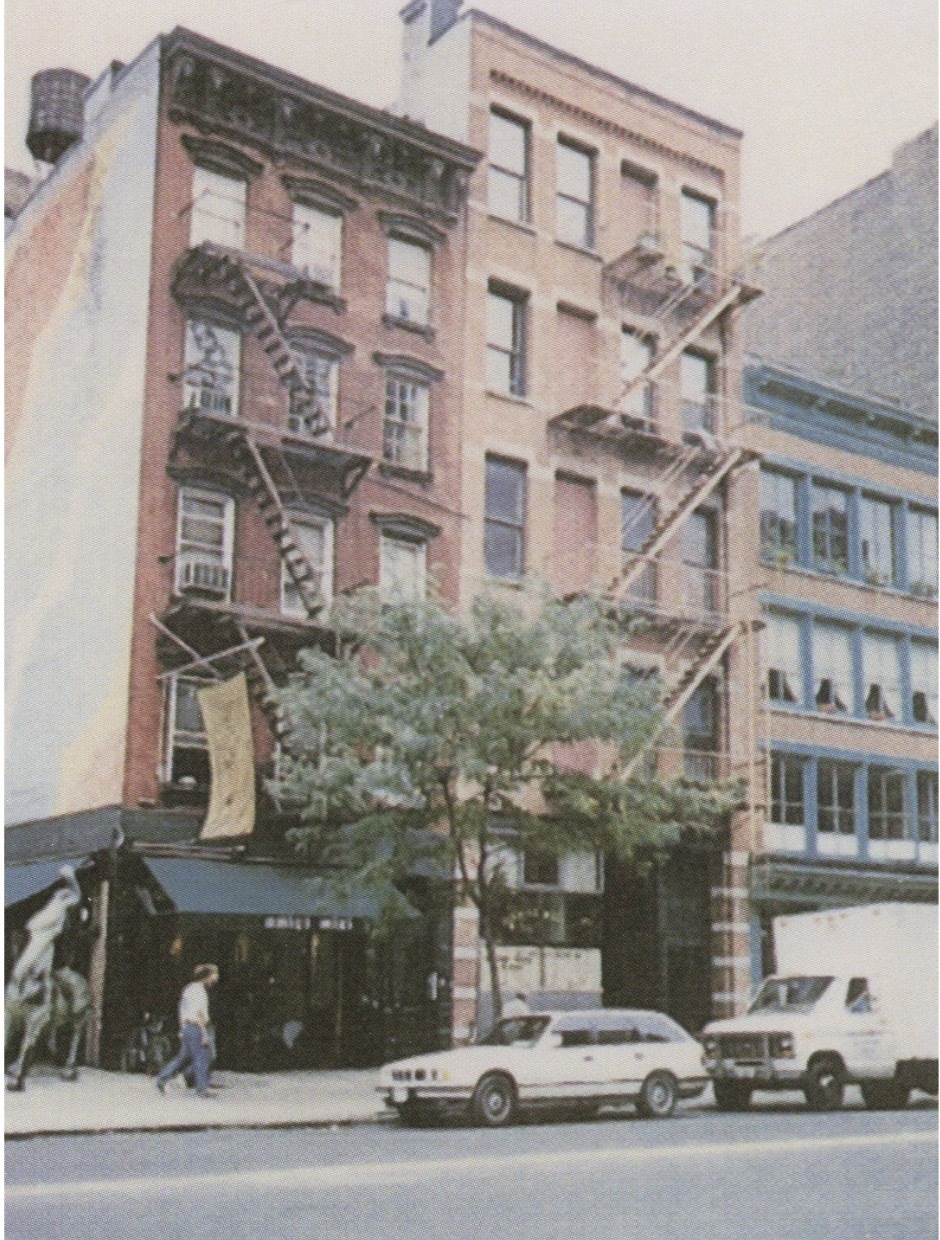

The exterior of Xia Yang's studio building in New York.

In 1987, Xia Yang returned to the "Mao Mao Ren" series, incorporating more elements of folk art, such as Guan Gong and door gods, than he had thirty years earlier. In 1992, Xia Yang left New York's SoHo neighborhood and returned to Taiwan, settling in Beitou. He revisited the "lion holding a sword," a folk art form widely practiced in Fujian and Taiwan, through his own abstract language, transforming it into numerous variations and presenting it repeatedly.

Xia Yang, “Lion,” 2018, sculpture

Ten years later (2002), Xia Yang settled in Shanghai.

"Leaving the mainland wasn't an option for us back then. We had no food to eat." Now returning to Shanghai, Xia Yang calls it "fate."

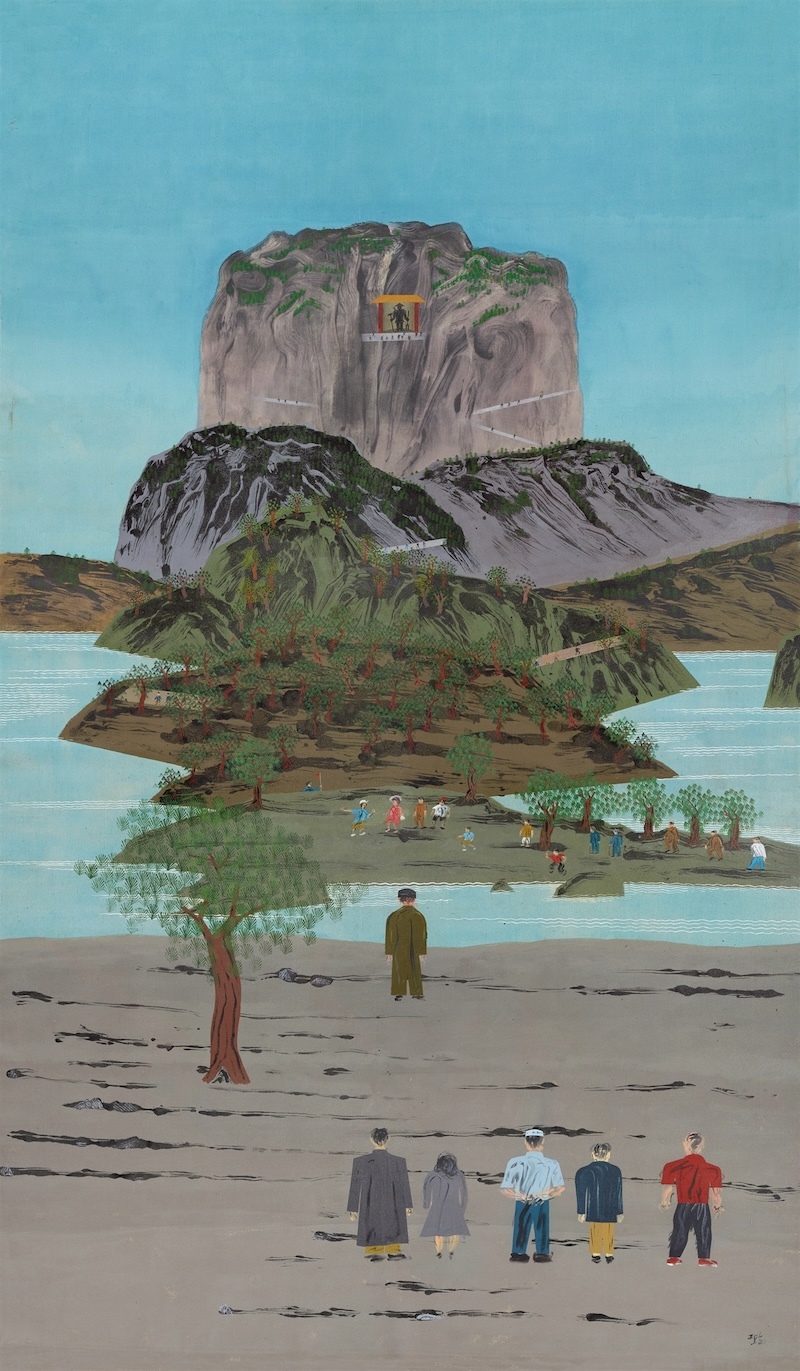

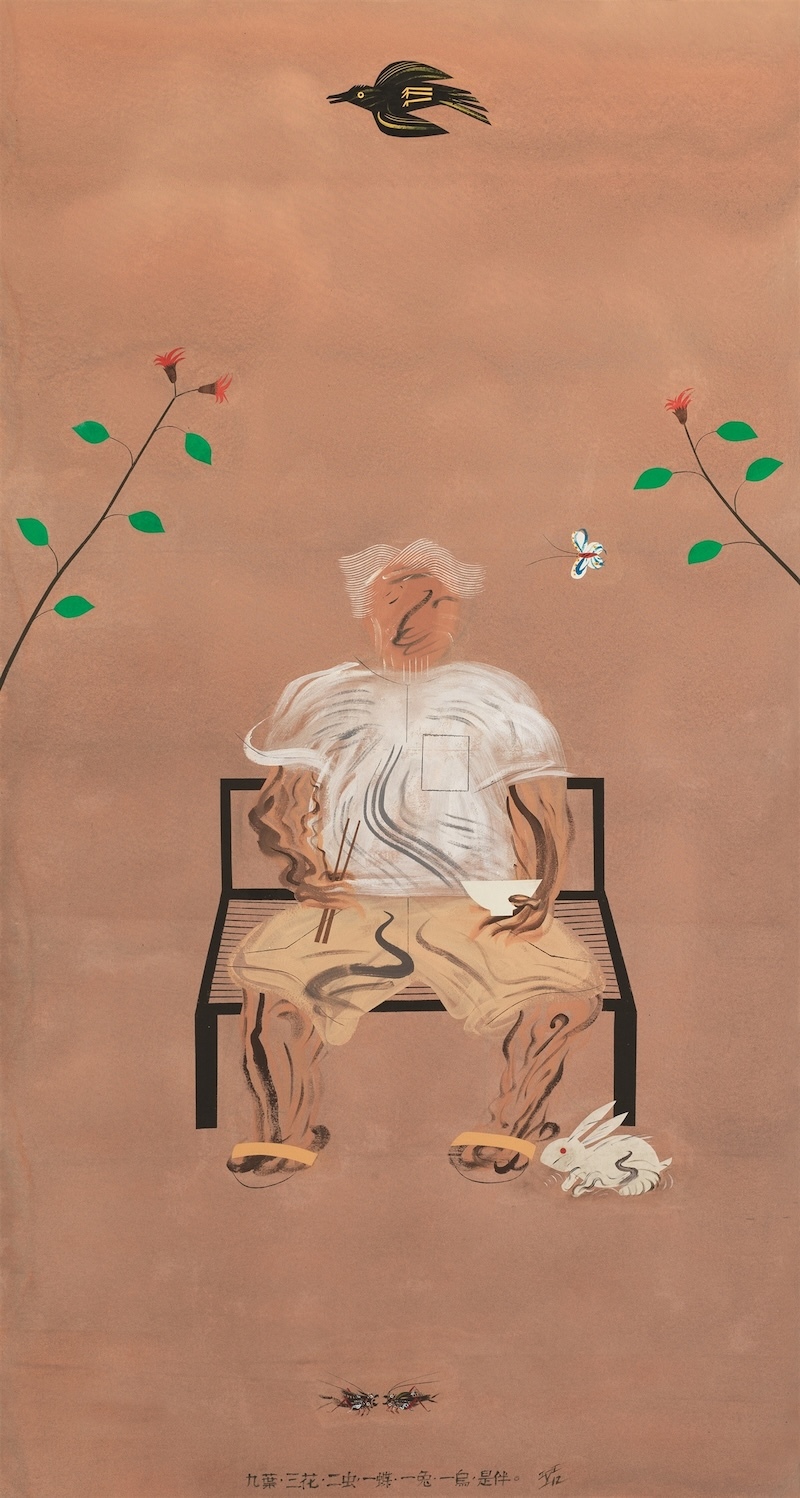

In recent years, Xia Yang's work has become more relaxed. He often depicts landscapes, flowers and birds, mountains and rivers, and figures, with a sense of ease and ease that returns to nature. In these works, classic literati imagery interweaves with distinctive elements of folk art: ink landscapes often reveal graphic structures reminiscent of paper-cuts, shadow puppets, or New Year paintings; the materials and textures of Western painting overlap with traditional Chinese freehand brushwork.

Xia Yang, “Landscape No. 5,” 2018, acrylic and collage on canvas

Xia Yang is currently painting "Yang Xiang Fights the Tiger," a Chinese folk tale. He plans to inscribe the painting alongside the painting: "Yang Xiang said: I want to eat my father, I'll strangle you to death." "Young people these days don't know these stories," Xia Yang says. "But I've been wrapped in layers of Chinese culture since I was born. No one would ask you to paint like this; it's just been ingrained in me since I was a kid."

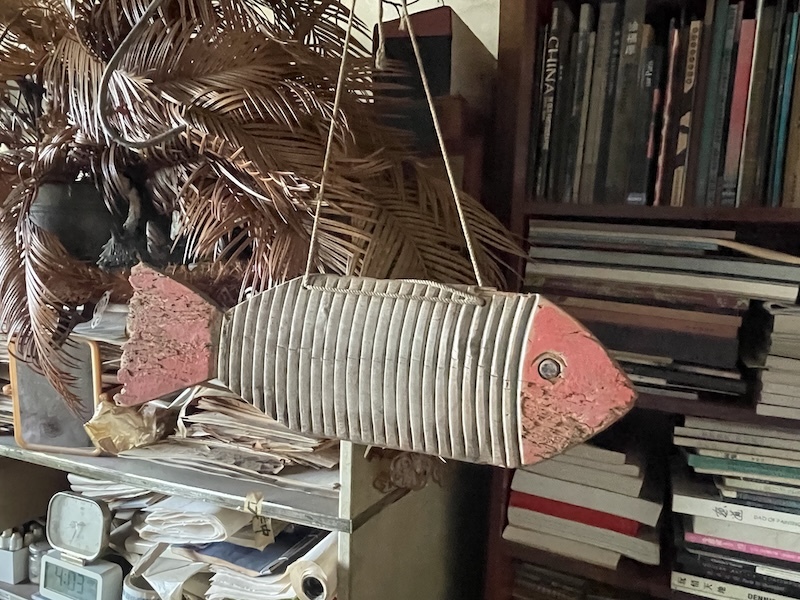

In this studio-cum-apartment, the graffiti-like writing on the wall, the books on the shelves, and the randomly placed small ornaments all silently reveal Xia Yang's experiences and connection with Chinese culture.

Display in Xia Yang's study.

Things will turn around if you take your time: Freedom of materials and folk colors

"We need to change the material, revitalize the thinking, and pay attention to the people."

Now 93 years old, Xia Yang carries a rich tapestry of life. Wearing a hat he painted himself, he is incredibly transparent and at ease, yet "follows his heart without breaking the rules."

He would say, mysteriously, like an old mischievous boy, "Let me show you a magic trick." Then, he would pull out a Coke bottle with the words "Things will turn out well if you take your time," and declare, "This is my lifeline for painting." It contained a "drying slow agent" he had mixed himself, suitable for acrylics.

"I currently paint with acrylics, which I can use on all kinds of materials. I can use this to wipe off the acrylic, or it can dry slowly. If I want it to dry quickly, I use a hair dryer," he said with a smile. For Xia Yang, acrylics represent a relaxed rhythm and open possibilities, freeing the painting from being constrained by the material.

Xia Yang, “Landscape VI: Farmer’s Monument,” 2020, acrylic and collage on canvas

His "landscapes" are similar to Fan Kuan's "monumental" style, but they're painted on canvas rather than rice paper; and instead of ink, they employ acrylic and paper-cutting techniques. Of course, he's not opposed to ink painting, but "due to the limitations of the medium, it's difficult to create something new. The disadvantage of using rice paper in Chinese painting is that it can't be modified, which leads to stereotyping. For example, the axe-chopping texture and hemp-wrapped texture—once the brush is put down, it's a fixed pattern, limiting freedom." He also believes that literati painting is excellent, its simplicity and endless charm, but "it's only one part of Chinese art. 'Ink has five colors' isn't enough; the color aspect has been extended to the folk. Talking too much about literati art is like missing at least half of Chinese art." Xia Yang often emphasizes this. He believes that folk art contains a wealth of wisdom and advocates building more folk art museums and bringing classic folk art into kindergartens so that children can be exposed to it from a young age.

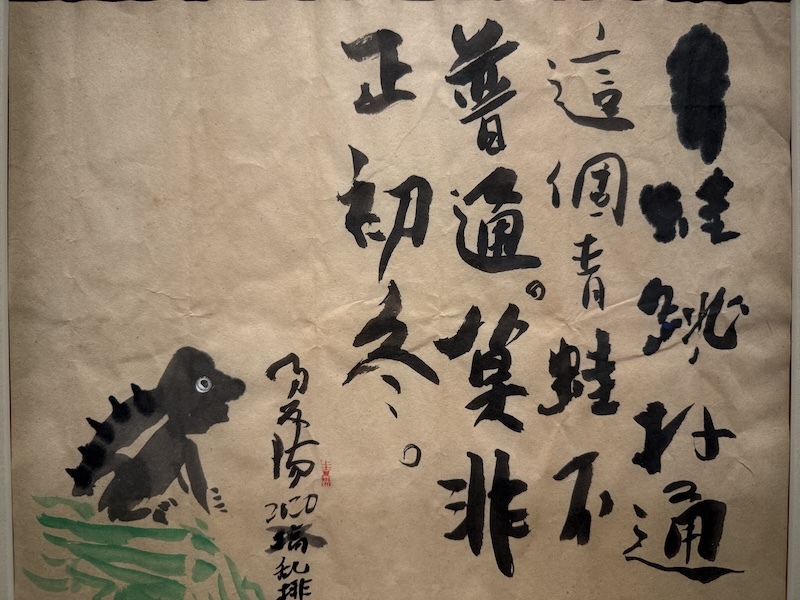

Xia Yang's works

In addition to the spontaneous nature of folk art, Xia Yang also emphasizes that "writing" predates "calligraphy," and that writing itself stems from emotion. The lines of writing extend into various free forms, woven into Xia Yang's sculptures. "China emphasizes the concept of 'between similarity and dissimilarity.' By slightly loosening the 'similarity,' allowing the lines to flow more freely, and then incorporating media art, we have a broad, modern Chinese art."

"Writing" is posted on the wall of Xia Yang's study.

Xia Yang's studio in SoHo, New York, photographed using his homemade large-film camera.

I recall that at the Ding Liren and Xia Yang double exhibition at the Power Station of Art in Shanghai in early 2023, a reporter asked him if the writing of the characters in his works was related to his personal experiences. Xia Yang replied, "I don't know. Or you could ask ChatGPT." It's incredible that this answer came from a man who was 92 years old at the time.

A corner of Xia Yang's study

Now Xia Yang is 93 years old. He is more like an old naughty boy who seems casual but full of wisdom. He calls a small aluminum alloy sculpture "sitting" on the corner of the bookshelf in the room a "camera" and also makes a set of mobile phone selfie equipment. Almost every guest who comes to visit will receive a voice-controlled photo produced by Xia Yang.

Caught between "Chinese and Western, new and old," he constantly attempts to piece together the fragments, finding his own creative path. In this elevated studio, the graffiti on the walls and the old books on the shelves, like the landscapes, furry figures, and door gods he paints, together form a universe, a footnote to his life after wandering and encountering obstacles.

Xia Yang, “Nine Leaves, Three Flowers, Two Insects, One Butterfly, One Rabbit, One Crow, Companions,” 2012, acrylic on canvas