In the first half of the 20th century, Chinese and Western cultures clashed dramatically, and Chinese art was undergoing a difficult transformation from tradition to modernity. A group of pioneers, harboring ideals of artistic innovation, either returned to China with advanced Western art theories to explore new frontiers, or challenged the boundaries of traditional painting to seek breakthroughs, and even sowed the seeds of modern art education in schools. Among them, France, as the world's center of modern art at the time, became the preferred destination for Chinese students studying abroad. Whether it was Xu Beihong, Liu Haisu, Lin Fengmian, or Wu Dayu, Pang Xunqin, after returning from their studies abroad, they all devoted themselves to education, establishing or serving in art schools, forming modern art societies, etc., building the core position of modern art education in China, and together completing the leap of Chinese art from tradition to modernity through different paths.

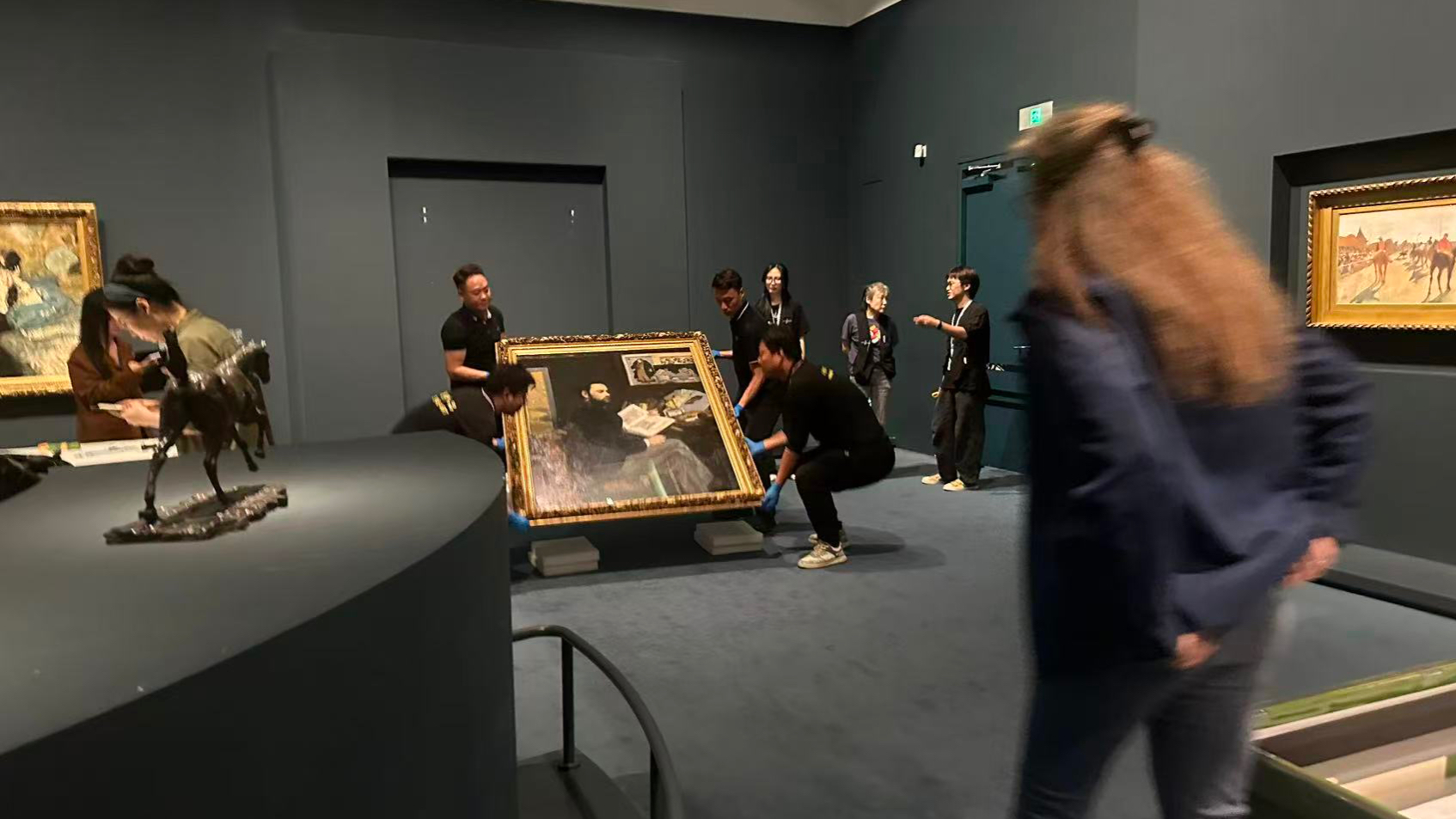

The Paper learned that a major highlight of the upcoming China Guardian 2025 Autumn Auction is a group of artists who studied in France. The works presented include not only works by Western masters who influenced these artists, but also artistic classics left by these artists, witnessing the innovation and transformation of modern Chinese art over the past century.

Pablo Picasso's "Woman with a Hat"

Interestingly, this special auction featured a rare work by Pablo Picasso, who lived in the French suburbs—"Woman with a Hat." In the 1920s and 30s, when pioneers like Xu Beihong, Liu Haisu, and Lin Fengmian studied in France, Picasso's modernist ideas primarily attracted artists like Liu Haisu and Lin Fengmian. Xu Beihong advocated realism and did not particularly admire Picasso or Impressionism, while the modernist camp represented by Liu Haisu and Lin Fengmian revered Cézanne, Van Gogh, and Picasso, attempting to integrate Western modern art concepts into Chinese art education and creation.

"Woman with a Hat" was painted in June 1965. The subject of the painting, Jacqueline Roque, was Picasso's last wife and his muse and model during the final stage of his artistic career. From 1954 onwards, Jacqueline in various poses became the theme of his later works. Picasso regarded Jacqueline as "a haven of unconditional love and support."

Jacqueline wearing a hat

Pablo Picasso, Woman with a Hat, 1965, oil on canvas, 58×49cm

In this painting, *Woman with a Hat*, Picasso combines Jacqueline's frontal and profile views on the same plane. The wide brim of her hat casts a gentle shadow on her face, creating a contrast of light and shadow. The artist uses muted Hooker green and pinkish skin to depict the contrast in her cheeks, and then uses varying shades of green to simultaneously highlight his wife's high, prominent nose, deep-set eyebrows, bright eyes, beautiful lips, and chin contours. The work as a whole uses highly saturated pure colors such as red, green, blue, and yellow, as well as large blocks of planar composition, which are distinctive characteristics of Picasso's early Fauvism influenced by Matisse. At this time, however, it has been transformed into his own "graffiti-like" language, forming a free and complex style. The overall brushstrokes are free and flowing, highlighting the charm of simple composition in its simplicity, as if capturing Jacqueline's deep, mysterious, and charming temperament at will, and also expressing his deep love for his wife.

Li Tiefu's "Fish and Cabbage"

Li Tiefu, Fish and Cabbage, Oil on canvas, 1940s, 62×77cm, formerly in the collection of the Zhao Yu family.

Li Tiefu was the first Chinese oil painter to study in the West and gain international recognition, and is known as "China's first oil painter." He was also a pioneer of the Chinese democratic revolution, donating all his wealth to the revolution. He holds an irreplaceable position in the history and development of modern Chinese art, and Sun Yat-sen inscribed the title "Giant of the East Asian Painting World" in his honor.

The painting "Fish and Cabbage," presented here, was completed in the 1940s and comes from the former collection of Zhao Yu. It differs significantly from Li Tiefu's still-life oil paintings that have previously circulated in the market. Li Tiefu's still-life paintings of fish typically use a white porcelain plate to hold fresh fish, establishing a black-and-white relationship before placing a few fruits and vegetables against a dark background to form a balanced triangular composition. However, "Fish and Cabbage" breaks this convention. The fathead fish is not placed on the plate as is customary, but rather arranged vertically on a dark green tabletop alongside a dark blue porcelain vase, cabbage, and green peppers. The objects are both interwoven and separated, especially the placement of the porcelain vase, where the overlapping of highlights and the outlines of the fish is intriguing. This vertical composition gives the painting a stronger sense of dynamism and rhythm, highlighting the contrast of light and shadow created by natural light on the surfaces of the objects. Comparing this to two similar compositions in the collection of the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts Museum reveals that Li Tiefu was actually developing a completely new compositional paradigm through such experiments.

As Li Tiefu said in his later years when he looked back on his life, "I have only two great passions in my life: revolution and art." Perhaps for him, the two were inseparable, as the spirit of revolution had long been embodied in his artistic practice through his years of creation.

Xu Beihong's "Samson and Delilah"

Xu Beihong, Samson and Delilah, oil on canvas, 1933, 125×150cm, formerly in the collection of Sun Peicang.

Xu Beihong was the founder of China's modern art education system. He studied in France in his early years, where he systematically mastered Western classical painting and drawing techniques. After returning to China, he taught at the Department of Art of National Central University and Beiping Art College (the predecessor of today's Central Academy of Fine Arts), and presided over the administration of Beiping Art College. With "realism" as its core, he thoroughly reformed modern art education, and his ideas have had a profound influence to this day.

The oil painting "Samson and Delilah" was commissioned by Xu Beihong from his friend Sun Peicang during his 1933 European exhibition tour, and was a copy of a work by the Dutch master Rembrandt. Sun Peicang was an important art educator in the early Republic of China and possessed a large collection of masterpieces. He met Xu Beihong in France in the 1920s and they became close friends. Later, the two traveled to Berlin together and both greatly admired Rembrandt. Xu Beihong even made a copy of Rembrandt's "The Second Lady" and presented it to Sun Peicang. This painting, "Samson and Delilah," is another testament to their deep friendship and shared artistic interests.

Compared to Rembrandt's original, Xu Beihong's copy is extremely close in details such as brushstrokes, light and shadow, and color relationships, preserving Rembrandt's typical bold style. The rich layers of detail in the painting—the subtle expressions of the people, the exaggerated body movements, and even the metallic reflections on the armor—are delicately presented, creating a tense atmosphere. Even under the dim lighting conditions of the museum, Xu Beihong was able to reproduce the complex visual effects of Rembrandt's painting, demonstrating his exceptional modeling skills and profound understanding of the colors and composition of classical European painting.

Fang Junbi's "The Hermit"

Fang Junbi, *The Hermit*, 1935, oil on canvas, 97.5 × 78.5 cm. From the artist's family.

In the grand panorama of 20th-century Chinese art, Fang Junbi undoubtedly stands out as a unique and resilient bright spot. As the first Chinese woman to be admitted to the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, her artistic career began at the heart of Western modernism, yet it was always permeated with a deep longing for the spiritual homeland of the East. Her 1935 oil painting on canvas, *The Hermit*, is not only a representative work of Fang Junbi's mature period, but also a "spiritual self-portrait" bearing the imprint of the era and her personal aspirations. With its exquisite fusion of Eastern and Western techniques, profound cultural connotations, and tranquil literary temperament, this work has become an important text for understanding Fang Junbi's artistic world and the intellectual journey of the Republic of China era.

The most prominent feature of this painting, "The Hermit," lies in its visual language construction within a cross-cultural context. Fang Junbi, with his masterful Western oil painting techniques, interprets a theme imbued with the spirit of traditional Chinese aesthetics. In the foreground, the treatment of rocks and vegetation reveals the unique weight and texture of the oil painting medium. Through layers of deep green, ochre, and dark blue, the artist creates an almost oppressive and somber atmosphere. The brushstrokes are decisive and expressive, not for the sake of meticulously reproducing nature, but to shape the volume and vigor of the rocks. This emphasis on "volume" and "texture" is a direct reflection of classical European painting training. However, the viewer can also sense the shadow of "cunfa" (texturing strokes) in Chinese landscape painting—those short, abrupt brushstrokes, as if using oil paint to write the sinews and veins of the rocks.

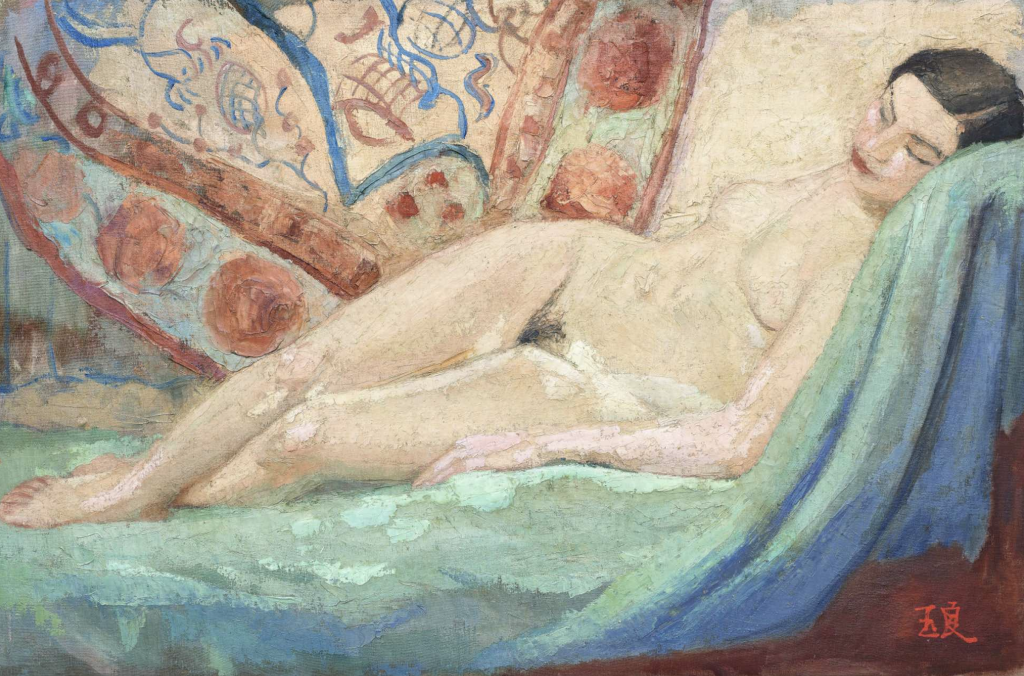

Pan Yuliang's "Qiluo Yumian"

Pan Yuliang, "Sleeping Beauty," circa 1940s, oil on canvas, 59×90cm, private collection in France; acquired by a major Asian collector from the above source in 1992; acquired by a major Asian collector from the above source in 2007.

Nude women were a central theme in Pan Yuliang's art throughout her life. While studying painting at the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts founded by Liu Haisu in 1918, she developed a particular interest in the female nude. After studying in France, the subject matter remained primarily nude painting. In 1927, at the age of 32, Pan Yuliang won a gold medal at the Italian National Art Exhibition in Rome with her oil painting "Nude Woman," a highly prestigious achievement in the Chinese Western painting world at the time, representing a significant accomplishment in the field.

In June 1940, Paris fell during World War II. As her studio was confiscated by the German army, Pan Yuliang moved to the suburbs of Paris, where she devoted herself to the study of nude painting and created a large number of works, which garnered widespread attention. This allowed Pan Yuliang to shine on her second trip to France, and her outstanding artistic achievements were awarded the National Gold Medal by the French government in 1945.

"Sleeping Beauty" was created during this period. In this painting, Pan Yuliang abandoned the strong contrasts of light and shadow commonly used in Western oil painting, integrating the contours of the female figure into color and form. She used color to shape form, constructing the softness of the female form through rich, subtle colors and almost invisible brushstrokes. For example, there is no abrupt boundary between the arms and torso; only between the legs and at the junction of the calves and ankles are the changes in light and shadow using warm and cool colors to suggest volume and transitions. Pan Yuliang skillfully used gentle contrasts of similar colors to express the three-dimensionality of the figure: pearl white, pink, and pale yellow were used to brighten the lit areas, while the inherent stone green of the carpet was boldly incorporated into the shadows on the legs. This allows the human figure to be harmoniously unified with its environment in the same light and color atmosphere. The brilliance of "Sleeping Beauty" lies in the light, color, and texture. The three elements work together to create a vibrant beauty. The overall atmosphere is serene, exuding an Eastern sense of restraint and inner gentleness.

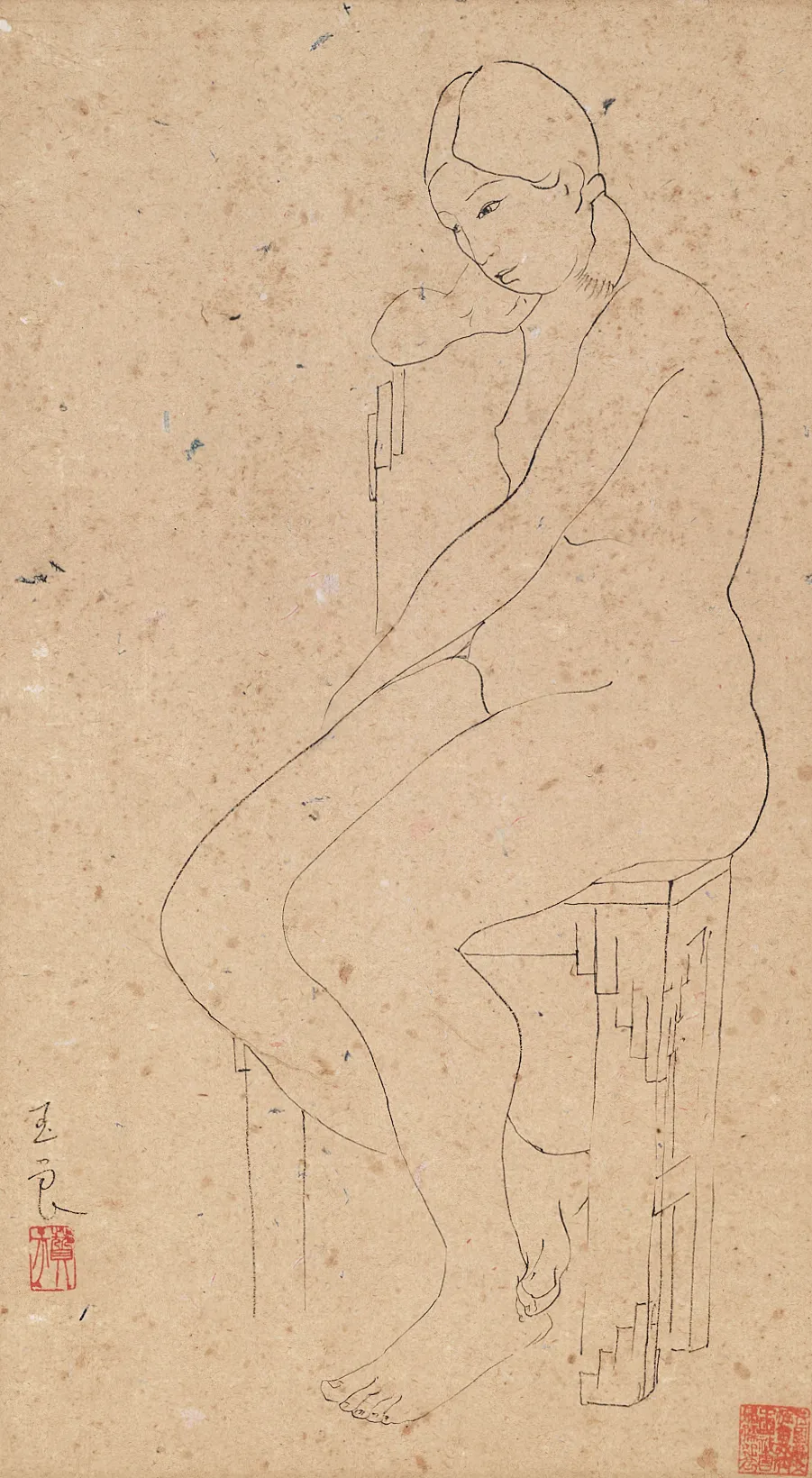

Pan Yuliang (1895-1977), *Seated Female Nude*, ink on paper, 1937-1938

In January 1938, the French Women's Association held a lottery to raise funds for women and children affected by the Sino-Japanese War, with Chinese artworks as prizes. Pan Yuliang and members of the Chinese Artists Association in France assisted in collecting artworks and preparing for the event. The ink painting "Seated Female Nude" presented here is one of the works submitted for the event.

Liu Haisu's Bali scenery

Liu Haisu, *Scenery of Bali*, 1940, oil on canvas, 60×73cm

After two trips to Europe in 1935, Liu Haisu's period of artistic accumulation was essentially complete, and he entered a stage of building momentum for his creative peak. "Sketches of Bali," created in 1940, is a precious testament to this important turning point.

During this period, Liu Haisu produced fewer oil paintings, especially after Shanghai became an isolated island. He almost stopped painting until 1939 when he was invited to travel to various parts of Southeast Asia to raise funds for the war effort, at which point he resumed painting. According to Liu Haisu's letters, he created more than twenty oil paintings during his sketching trip in Southeast Asia in 1940. However, due to the war and the hardships of his travels, only about ten of these works have survived to this day—twelve of which are in the collection of the Liu Haisu Art Museum, making the number available on the art market extremely rare.

In "Sketches of Bali," Liu Haisu employs a low viewpoint, with the foreground land and vegetation rendered in deep ochre and dark green, short, overlapping brushstrokes creating a dense rhythm and texture. The midground water surface, rendered in bright gray-white with a flowing rhythm, serves as a visual breathing space between the foreground and background. In the distance, mountains and swirling clouds are condensed into large shapes within cool colors of deep blue, gray-white, and a hint of purple, rendered with bold and vigorous brushstrokes.

"Sketches of Bali" is both a tribute to the tropical landscape and a cultural monument etched in the midst of war. The artist infuses his personal feelings and cultural awareness into the exotic scenery, keenly capturing the fleeting changes of tropical light and shadow while showcasing a cross-cultural perception of the nature of another land. Every stroke of the brush is a vivid projection of the individual spirit amidst cultural fusion. With the smoke of war cleared, the surging vitality between the heavy brushstrokes—the profound poetic essence of the East, the color and light revolution of the West, and the artist's passionate heart—still beats ceaselessly on the canvas.

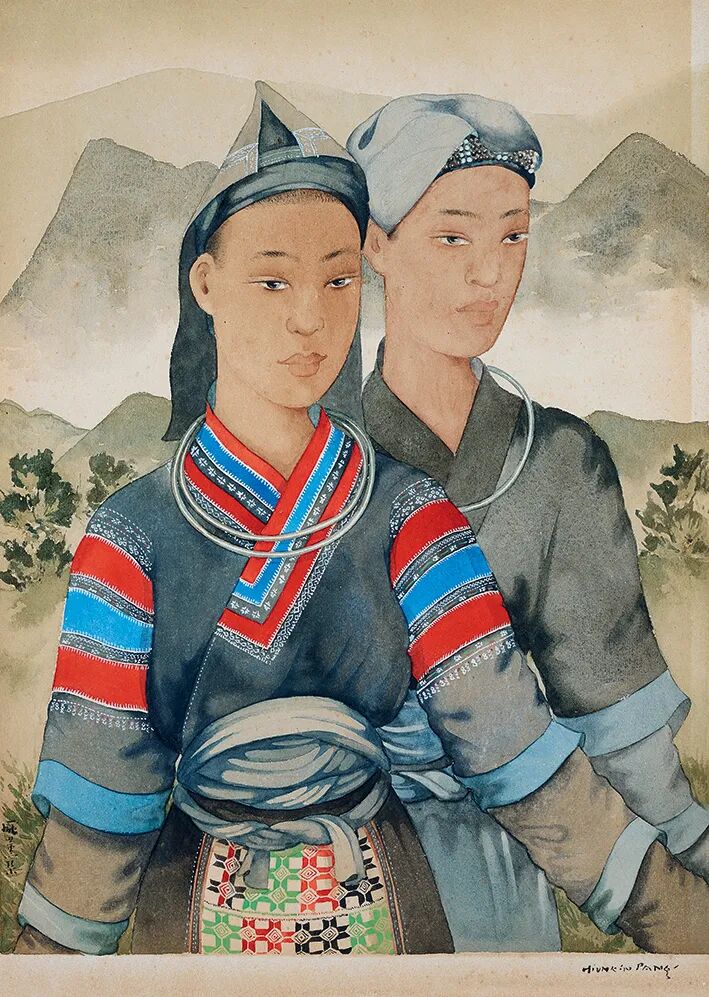

Pang Xunqin's "Ode to China"

Pang Xunqin, "Ode to China", early 1940s, ink and color on paper, 35×26cm

In 1939, Pang Xunqin was appointed as a researcher at the Preparatory Office of the Central Museum. Together with ethnologist Rui Yifu, he conducted in-depth investigations of folk art in Miao areas of Guizhou and Yunnan. His footprints covered more than eighty villages. He not only systematically collected and organized a large amount of information on Miao costumes, brocades and silver ornaments, but also personally participated in the daily life and ritual activities of the locals with great cultural respect and emotional investment.

"Ode to China" was painted based on materials collected during field research in Miao villages between 1939 and 1940. The artist combined the planar modeling of traditional Chinese painting with the realistic techniques of Western painting, giving the painting a highly decorative treatment to express its stylistic characteristics. Pang Xunqin, a master of line drawing in the 1940s, was keen-eyed and skillful, his brushstrokes flowing like snakes and delicate as silver hooks, making this work exceptionally masterful in terms of form. The intricate folds of clothing and accessories are depicted perfectly. For example, the wide border decorations on the front of the upper garment and the arms are characteristic of the "Flower Miao" of Guizhou, made with delicate embroidery, bright colors, and diverse patterns, creating a textural contrast with the light-colored tie-dyed fabric at the waist. The artist consciously weakened the sense of space through meticulous detail, making the painting feel fresh and bright, thus greatly highlighting its decorative charm. In contrast, the clear faces and slightly melancholy expressions of the figures reflect the artist's artistic conception of elegant refinement within simplicity.

Compared to many painters of this period who were dedicated to integrating Chinese and Western painting techniques, Pang Xunqin was undoubtedly at the forefront of this group. Dr. Gao Meiqing of Hong Kong commented on these works in her book "Chinese Painting in the 20th Century": "The use of lines and the fuzi pattern-like shapes give these works a soft, beautiful charm and a strong decorative quality... Pang Xunqin formed her own artistic expression through the fusion of Chinese and Western art."

Sha Qi's "Ancient Plum Blossom Melody"

Sha Qi's "Ancient Plum Blossoms and Clear Sounds," oil on canvas, 1942, 82×64cm, private collection of Queen Elizabeth of Belgium (1876-1965), bears the Belgian Royal Collection label "RE" on the back.

In 1937, Sha Qi went to Europe for further studies, entering the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Belgium, where he studied under the director, A. Bastien. Due to his outstanding academic performance, he won the "Gold Medal for Outstanding Artwork." After graduation, Sha Qi continued to create art in Belgium as an independent artist. The highlight of his artistic career came in 1942 when one of his oil paintings depicting ladies playing music was purchased by Queen Elizabeth of Belgium; this work is "The Sound of Ancient Plum Blossoms," which is the subject of this exhibition.

Music was a central theme in Queen Elizabeth's life, and Shaqi, using the title "Concert" and depicting a scene of ladies playing music, not only offers a modern interpretation of a traditional Chinese subject but also metaphorically represents Europe's wartime yearning for peace. The painting originates from the tradition of ancient Chinese paintings of court ladies: four elegantly dressed ladies stand under the shade of trees, their faces serene and reserved, their attire vibrant, holding traditional Chinese instruments such as the pipa, sheng, and xiao, dancing gracefully to the music. The painter employs scattered perspective, treating the space more flatly; the thick layers of yellow-green oil paint reveal strong brushstrokes and clear chisel marks, full of texture and dynamism—a signature technique of the artist at the time. Through the alternating use of fine and bold color blocks, Shaqi sculpts the slender figures of the ladies; the rich brushstrokes do not detract from the richness of the colors or the fullness of the forms, giving a sense of intimacy and naturalness. The white plum blossoms on the branches, the old tree's oriental, winding shape, the landscape-like grass, and the imagery of water and mountains all exude vitality under the painter's brush, clearly demonstrating Eastern characteristics.

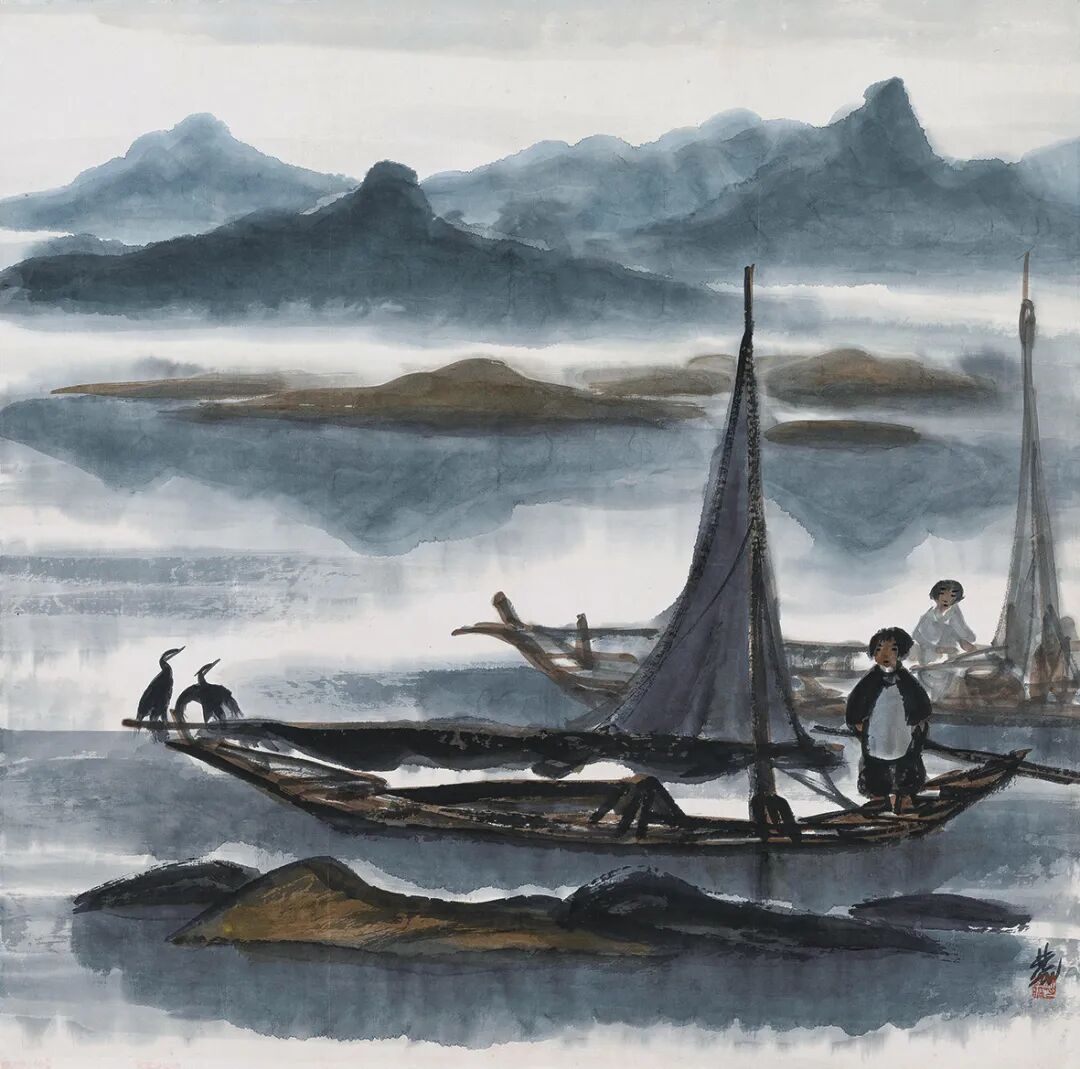

Lin Fengmian's "Fishing Boats on Misty Waves at Dusk"

Lin Fengmian, "Fishing Boats on Misty Waves at Dusk," ink and color on paper, 1950s, 67×67cm.

Lin Fengmian was an important figure in modern Chinese art education, reconstructing the modern framework of Chinese art education with the core concept of "harmonizing Chinese and Western art." In 1928, at the invitation of Cai Yuanpei, he co-founded the National Academy of Art (now the China Academy of Art) with Wu Dayu and Lin Wenzheng, proposing the educational principle of "inclusiveness and academic freedom," and for the first time deeply integrating the Western modern art education system with traditional Chinese culture.

Lin Fengmian's personal creations are also a unique example in modern Chinese art. His work is not simply a patchwork of Western techniques and Eastern themes, but rather a pursuit of a profound spiritual fusion, which is directly reflected in his landscape paintings. For instance, in this painting, "Fishing Boats on Misty Waves at Dusk," the treatment of many images reveals Lin Fengmian's "betrayal" of traditional Chinese ink painting: the distant mountains are primarily rendered with ink washes, without any texturing or rubbing, thus shaping the volume, contours, and interplay of light and shadow of the peaks. At the same time, the somewhat blurred boundaries between the images seem to be a reaction against the procedures of traditional Chinese painting since the Song and Yuan dynasties. Lin Fengmian depicts objects with emotion, imbuing forms with spirit, and blending genuine feelings and poetic sentiment into the painting. His work is unadorned yet naturally charming, which is precisely the high realm of authentic Chinese artistic style and the value orientation of painting aesthetics.

Li Chaoshi's sunflowers all face the sun.

Li Chaoshi, "Sunflowers Facing the Sun", 1963, ink and color on paper, 66.5×85.7cm.

"Sunflowers Facing the Sun" was created in 1963. It is the largest pastel painting among Li Chaoshi's existing works, and it is also a very special one in terms of composition and color. It is extremely well preserved and very rare.

"Sunflowers Facing the Sun" depicts two sunflowers blooming symmetrically in a mirror image. Unlike the artist's other floral works, this piece employs a bold, close-up, full-page composition, enhancing the visual tension and sense of presence of the flowers. This approach stems from both the sunflower's vibrant and large size and the influence of the era in which it was created.

"Sunflowers Facing the Sun" fully utilizes the characteristics of pastel painting, which is suitable for harmonious and rich tonal variations. With unrestrained brushstrokes, it vividly displays the vibrant vitality of the flowers, showing "simple and unpretentious style, a master's touch". It is an epitome of Li Chaoshi's pastel art achievements throughout his life.

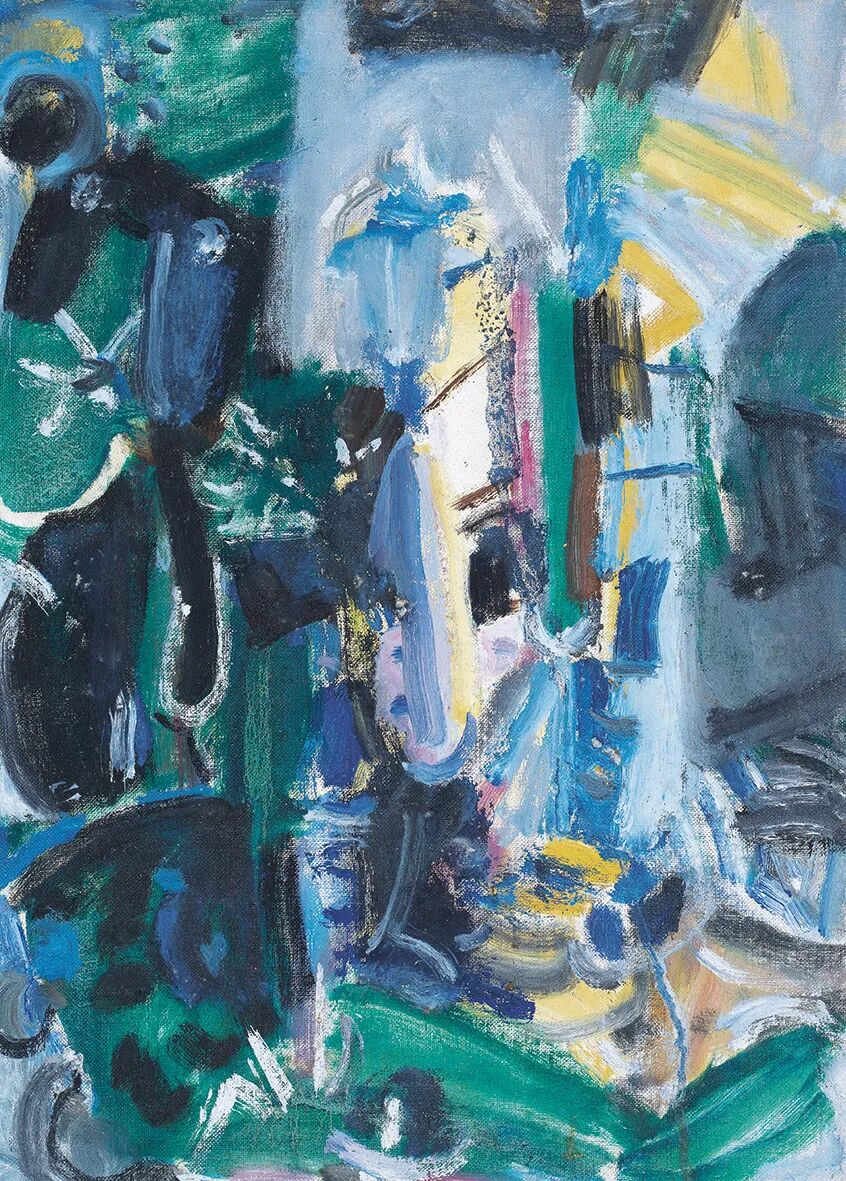

Wu Dayu's "Duoyun"

Wu Dayu, "Duoyun", oil on canvas, circa 1980s, 53×38 cm

Like Lin Fengmian, Wu Dayu was one of the founders of the National Academy of Art (now the China Academy of Art). Through his pioneering teaching practices, he cultivated international masters such as Zao Wou-Ki, Chu Teh-Chun, and Wu Guanzhong, injecting modernist genes into China's modern art education. His contributions profoundly reshaped the development trajectory of Chinese art in the 20th century.

"Duoyun" presents Mr. Wu's most classic color tones and composition from the 1980s with free and unrestrained brushstrokes, exuding vitality and a unique temperament. What is most striking is its exquisite color expression, with a wide color gamut that transitions from light to dark and from warm to cool. The right half is bright, using gamboge, magenta, and other colors to depict town streets and alleys, showing layered space; the left half is dark and cool, with Prussian blue, dark green, and other colors to create lush foliage, adorned with pink and white flowers, and long lines extending from the greenery to form green slopes. The deep blue and dark green balance the lightness of the right half, and the composition is well-balanced, with visual undulations and vibrant life.

Zao Wou-Ki, 14.12.71

Zao Wou-Ki, oil on canvas, 1971, 130×195 cm. Galerie de France, Paris, France; private collection, France (acquired from the gallery by the current owner in 1986).

Created in 1971, "14.12.71" encapsulates Zao Wou-Ki's completely new reconstruction of space, representing the culmination of his work from the 1950s and 60s. According to "The Second Chronological Collection of Zao Wou-Ki," he created no more than twenty oil paintings with a number greater than 120 in the early 1970s. This work is the largest horizontal piece among them, perfectly blending traditional antiquity with modern vision through its weathered and powerful bronze hues. It carries the dual significance of Zao Wou-Ki's stylistic evolution and spiritual rebirth, truly a masterpiece in which he transcends his own culture and pursues universal meaning.

In the monumental horizontal work "14.12.71," the blank spaces at the top and bottom are ingeniously designed, as if opening up another space-time within the painting, making the visual layers deeper and more profound. The central color area thus appears more concise and compact, and the ink lines appear more unrestrained and free, pushing the tension between movement and stillness to its extreme. The long horizontal format guides the viewer like appreciating a long scroll of traditional Chinese painting, requiring the passage of time and space to fully appreciate its contents. For Zao Wou-Ki, it was in 1971 that he bravely confronted and boldly utilized the use of blank space. At that time, he recounted: "In 1971 and 1972, I found myself unable to continue painting, so I returned to the techniques of ink painting. Because I had learned this tradition in school, I had no difficulty in handling it. But I did not like that absolute, almost magical randomness... This experience with ink painting helped me a great deal, giving me greater freedom and a broader perspective." By tracing the tradition of ink painting, between the tension of emptiness and the inspiration of chance, Zao Wou-Ki reshaped his artistic language, thereby opening up a brand-new creative realm.

Wu Guanzhong's "Palace Walls"

Wu Guanzhong, *Palace Walls*, 1972, oil on cardboard, 26.6 x 34.3 cm

For Wu Guanzhong, 1972 was a year of turning the tide. Having endured the long social movements and forced labor of the 1960s, the artist was not only banned from painting but also suffered from hepatitis for a long time. In 1972, his production team began allowing him to paint on holidays, even though he could only afford a small blackboard as a canvas and a manure basket as an easel—earning him the nickname "manure basket painter"—his accumulated creative energy exploded, leading to a fruitful period of artistic output. Simultaneously, his long experience in the countryside instilled in Wu Guanzhong the self-imposed requirement of "approval from the masses and applause from experts," gradually forming the concept of "a kite with an unbroken string." "The Palace Wall" was born in this context, witnessing the culmination of Wu Guanzhong's accumulated experience as his artistic journey returned to normalcy.

In the painting, towering trees occupy the visual center, their tender green leaves partially obscuring the mottled red walls, creating a contrast between red and green, ancient and new, horizontal and vertical. Tourists in various attire dot the scene like musical notes, with a particularly striking group of students in school uniforms waving red flags and colorful bus stop signs along the roadside, exuding the unique vitality of the new generation. This contrasts sharply with the iconic Wanchun Pavilion and Zhoushang Pavilion of Jingshan Park, creating a sense of scale, height, and foreground. Although the painting is composed of large areas of green and red, these large areas are also composed of inlaid smaller pieces, forming a rich layered effect where each element is intertwined with the others, showcasing the artist's meticulous planning before putting brush to paper.

In addition, Wu Guanzhong's "Morning in a Fishing Village," "Spring Trees," and "Portrait of a Lady," which are also presented at the same time, are also masterpieces of Wu Guanzhong's paintings.

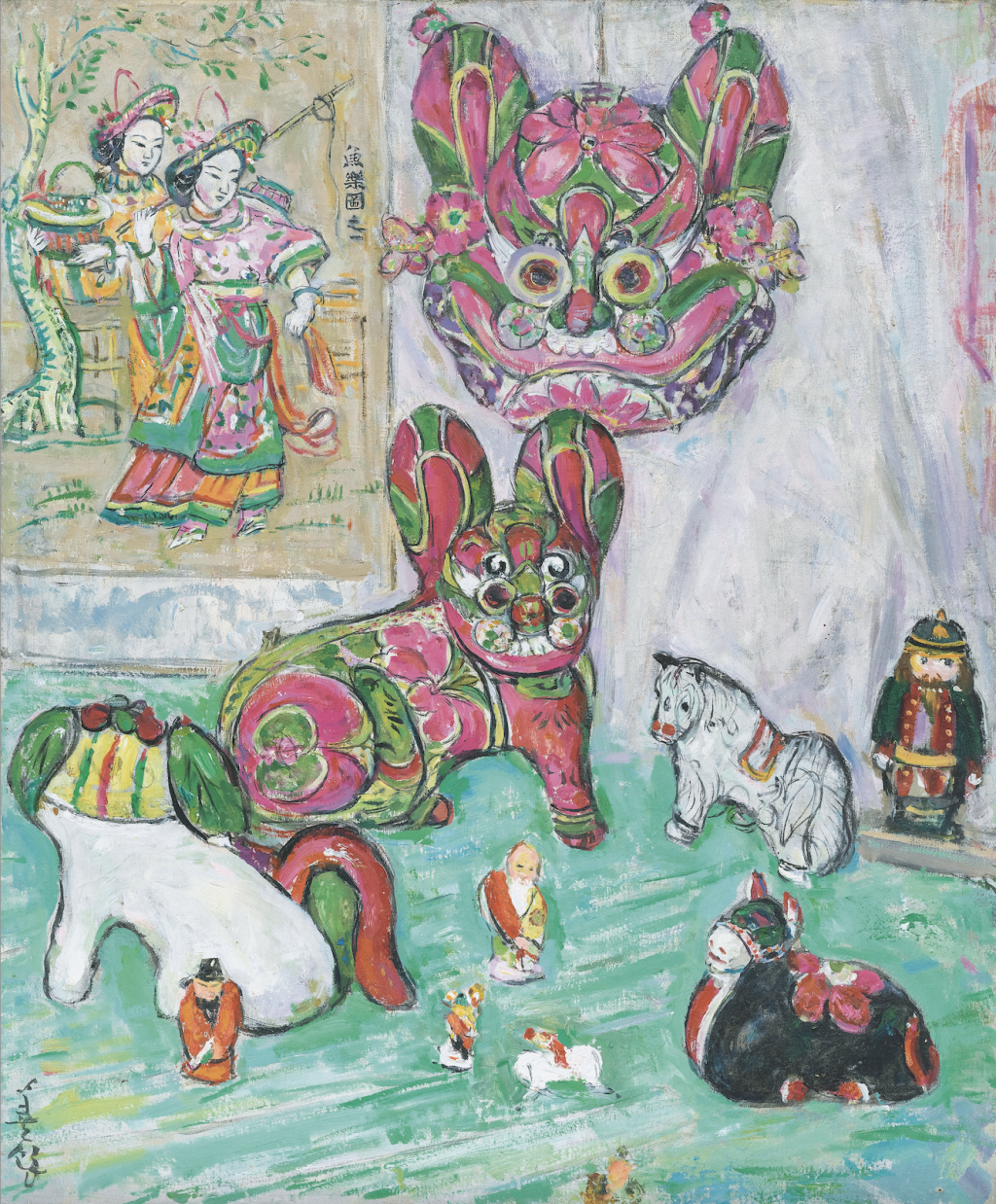

Hu Shanyu, *Chinese Toys*

Hu Shanyu, *Chinese Toys*, 1974, oil on canvas, 73×60cm, artist's family.

Like the Impressionist painters, Hu Shanyu not only sought the beauty of color in nature, but also used his studio as an important place to paint. In his small room by West Lake or in the classroom at the art academy, Hu Shanyu combined everyday objects such as flowers, fruits, ceramics, and toys, giving them new artistic meaning.

"Chinese Toys" is a representative still-life painting by Hu Shanyu, created during the mature period of his artistic career. It holds significant importance and is included in the artist's authoritative catalogue. Painted in 1974, after a period of turmoil during a particular era, Hu Shanyu was able to resume his creative work. At that time, his students brought back a batch of Fengxiang clay sculptures and New Year paintings from Xi'an. The vibrant colors and vitality of these folk art pieces deeply moved the artist, who poured his heart and soul into the painting. "Chinese Toys" has since been considered one of Hu Shanyu's most prized works, and he has politely declined numerous requests from friends to collect it, treasuring it to this day.

"Chinese Toys" is brightly colored and ingeniously designed. The picture uses the contrast of red and green as the framework for the color relationship of the whole flower. All the red and green have subtle differences in hue and color properties. By outlining with dark lines, the color blocks of different areas are unified, making the picture appear very rich and strong. The colors are bright but not vulgar, with a strong oriental charm and decorative beauty.

Hu Shanyu's achievements in oil painting are inseparable from his profound mastery of color. Besides absorbing much of the essence of Impressionism, he also deeply absorbed and applied the color relationships of Chinese folk art. In "Chinese Toys," the tiger and the cloth are predominantly painted in bright red and green, while incorporating the contrasting yellow and purple of New Year paintings and the wall, creating a vivid and harmonious visual foundation. However, the painter did not directly adopt the highly saturated colors of folk toys, but rather harmonized them with the brushstrokes and tones of oil painting: warm browns were blended into the red to make it richer; gray tones were added to the green, yellow, and purple to soften them. This treatment preserves the vibrant energy of folk colors (like the lively and auspicious red and green combination in New Year paintings) while giving the oil painting a rich texture. The tiger's stripes, blended with the oil paint, possess both the simplicity of folk art and the delicacy of Western painting, achieving a skillful balance between the vibrancy of folk art and the elegance of oil painting.

Zhong Ming, "He Is Himself—Sartre"

Painter Zhong Ming's 1980 work, "He Is Himself—Sartre," sparked widespread controversy in the art world regarding whether painters should possess individuality, causing a great uproar and becoming a milestone work in the "reform and opening up" era of Chinese art. "He Is Himself—Sartre" initiated the localization of Western thought and conceptual art, and together with Huang Rui's "Street Production Team's Embroidery Workers," it promoted the historic transformation of contemporary Chinese art from the "traditional realist paradigm" to "modern pluralistic exploration," possessing irreplaceable pioneering significance.

Zhong Ming (b. 1949), *He Is Himself—Sartre*, 1980, oil on canvas, 110×170 cm.

In 1980, Zhong Ming was in his early thirties. China was in the early stages of reform and opening up, with various new trends and ideas constantly emerging. Like most young people, he was full of curiosity about new knowledge and ideas, especially philosophy. On April 15, 1980, Sartre passed away. This inspired Zhong Ming's creative desire—he wanted to paint a portrait of Sartre. However, when conceiving the painting, Zhong Ming encountered a problem: how should he depict Sartre's strabismus (crossed eyes)? Because few people knew what Sartre looked like at the time, Zhong Ming, out of admiration for Sartre, was unwilling to directly depict the strabismus, but also did not want to change his appearance to mislead the audience. So he adopted a horizontal composition, placing Sartre in the lower right corner of the painting, and created a printmaking effect. He made modifications without losing the authenticity of the image, and titled it "He Is Himself—Sartre." This title also echoed Sartre's statement in his 1976 lecture entitled "Existentialism is a Humanism": "Human existence is self-creation."

In the upper left corner of the painting, Zhong Ming depicted a cup, which touches upon a core idea in Sartre's existentialist philosophy: the essence of a cup precedes its existence, while human existence precedes its essence. Through this painting, Zhong Ming expresses a cry for the meaning of painting, as he wrote at the end of "Starting with Painting Sartre—On Self-Representation in Painting": "Every artist explains himself in his creative motivation and behavior."

Looking back at 1980, it marked the first major breakthrough in the Chinese art world after the thaw. The emergence of masterpieces such as Luo Zhongli's *Father*, Chen Danqing's *Tibetan Series*, and Cheng Conglin's *Summer Night* initiated a process of correction, rebellion, and transcendence of the previous era's art. Among these, *He Is Himself—Sartre*, with its uniquely austere style and profound philosophical reflections, played a pioneering role in the subsequent '85 New Wave and even the rational and philosophical art trends of the 1990s, and will forever remain a part of Chinese art history.